I was born an intolerant, at least, when it comes to lactose type things, and throughout my life, I’ve never really been able to enjoy anything made with dairy, without having to suffer the consequences. As I’ve grown up, it’s gotten much better, and my reactions to anything with dairy have become less serious, but you’re never going to see me with a glass of milk in my hand.

Despite my allergy, like most people in Taiwan, when I hear the words “Linfengying” (林鳳營), there’s pretty much only one thing that comes to mind, and that’s one of Taiwan’s most famous brands of milk.

I suppose you could say that the milk is so well-known that even a foreigner who is allergic to dairy knows about it and if you’ve been here long enough, its highly likely that you’ve seen their iconic commercials on the television, seen their advertisements on public transportation, or have seen a bunch of cartons being delivered to your favorite coffee shop.

Things haven’t been going so great for the brand in recent years, though.

In 2014, what has since become known as the ‘Gutter Oil Scandal’ (劣油事件) erupted around Taiwan, embroiling several of Taiwan’s largest food conglomerates, resulting in massive public anger, protests around the country, prison sentences, the recall of thousands of products, and the revelation that mass food adulteration by food conglomerates had been suppressed from the public for decades. The scandal, which involved 240 tons of ‘gutter oil’ affected a wide range of products on Taiwan’s shelves ranging from cooking oil, rice, milk and alcoholic beverages. It also affected thousands of restaurants around the country.

At the center of the scandal was Ting Hsin International (頂新集團), one of Taiwan’s largest food producers, with a long list of subsidiaries under its umbrella, including the famed Linfengying Milk (林鳳營牛奶).

Link: Food safety incidents in Taiwan (Wiki)

The scandal caused considerable damage to Taiwan’s international image, and products that were being exported to international markets were pulled. For their part, the people of Taiwan took to boycotts of products produced by the company, and in one particular case, known as “Operation Knockout” (滅頂行動), people went to Costco to purchase Lingfengying Milk, opened the package, and then returned it for a refund. Although it seems quite wasteful, the reason for this was because the licensing agreement Costco has with its suppliers dictates that the producer had to absorb the losses on returns, instead of Costco.

The boycott of Ting-Hsin products and the milk protest resulted in tremendous losses for the company, and its owners, who the public blamed for the food safety scandal. Eventually, the protests were deemed successful as considerable financial damage was done to the corporation and the family who ran it, with some of them having to serve prison sentences.

It’s been more than a decade since the scandal erupted, and while the public is still quite wary about what happened, the Wei Chuan Corporation (味全食品), which separated from Ting Hsin in the aftermath of the scandal, revived the Weichuan Dragons (味全龍) professional baseball team, appealing to the nation’s love of baseball, as an attempt to repair their public image.

Obviously, I’m not here today to dwell on corporate greed, and something that a lot of people don’t actually realize is that ‘Linfengying’ isn't just the name of a brand of milk, it’s also the name of a small village in southern Taiwan, whose residents, mostly hard working farmers, had little to do with the scandal that erupted across the country.

Located within Tainan City’s rural Liujia District (六甲區), Linfengying is a small village where you’re likely to find more cattle than humans, so its probably not of much interest to most tourists, but it’s also a historically significant farming settlement. Dating back to Taiwan’s Kingdom of Tungning (東寧王國) era. It also just so happens to be home to one of the nation’s few remaining Japanese-era wooden train stations, and that nearly century-old train station, which remains in operation today has become one of the village’s most famous attractions.

Today, I’ll be introducing this beautiful little station as part of my ongoing project covering historic Japanese-era stations across the country. However, even though its the kind of place that I’m personally quite interested in, unless you find yourself traveling between Chiayi and Tainan on the train, it’s probably not one of those destinations you’re going to want to go out of your way to visit. If you’re a fan of the railway or Taiwanese history, though, its probably well worth a quick stop during you travels.

Rinhoei Station (林鳳營驛 / りんほうえいえき)

In order to start detailing the history of the train station, I’m going to have to start by helping readers better understand the village where it’s located. Obviously, as mentioned earlier, for the vast majority of people in Taiwan, the name ‘Linfengying’ is automatically associated with one of the nation’s most well-known dairy producers. However, if you ask most people where Linfengying is located, it’s unlikely that many of them would be able to give you a proper answer. One could argue that Geography isn’t a subject that the Taiwanese education system puts much emphasis on, but in this case, you can’t really blame anyone for having no idea where it is.

Located within northern Tainan’s Liujia district (六甲區), the village is geographically closer to Chiayi City than it is Tainan, and the strange thing is that it’s currently just a place name rather than an actual town. According to the government, Linfengying doesn’t have an official designation as a ‘village' or a ‘neighborhood', so if you look at the address for the station listed below, it’s a little confusing.

The longer you live in Taiwan, the more you’ll discover this kind of loophole, when it comes to small communities like this one, is quite common, especially when you travel further south. If you’re a local, you’ll tell people you live in Linfengying, but if you’re the local mailman, you just have to remember who lives where in order to do your job. Interestingly, this was a theme that was explored in the famed ‘Cape No 7’ (海角7號) film directed by Wei Te-sheng (魏德聖). Nevertheless, in Linfengyin’s case, it probably isn’t very difficult for the mailman given that there are more cows living there than there are people.

The next thing we need to clear up with regard to this non-official-village is its name. If you’re familiar with Mandarin, you’re probably aware that the name ‘Linfengying’ (林鳳營) is an odd one when it comes to how places are named in Taiwan. In my article about Chiayi Train Station (嘉義車站), I mentioned how the name ‘Kagi’ was ‘bestowed’ upon the town by the Qing Emperor. Following a similar model, the name of this village originated during Taiwan’s Kingdom of Tungning Era (東寧王國) between 1661 and 1683 when Koxinga (鄭成功) and his army seized control of the island and expelled the Dutch. Upon their arrival, they were faced with an untamed land, and in order to keep their army well-fed, Koxinga spread his various battalions throughout Southern Taiwan, where they set up farming communities. Under instructions from one of the Kingdom’s most important civil administrators, Chen Yonghua (陳永華), new farming techniques were utilized for water-storage, and before long grain harvests became sustainable, allowing the short-lived kingdom to focus on cash crops to make the island economically self-sufficient.

Notably, most of these farming communities outside of the capital of Tainan were named, ‘Erjia’ (二甲), ‘Sanjia’ (三甲), ‘Sijia’ (四甲), ‘Wujia’ (五甲), ’Liujia' (六甲), and so on. If we keep in mind that the word ‘jia’ (甲) is an ancient way of referring to an army or soldiers, the towns were basically named, Second Army, Third Army, Fourth Army, etc.

However, one of the more northern of those farming communities was where General Lin Feng (林鳳), one of Koxinga’s most decorated warriors, garrisoned his troops. General Lin is known for a number of successful exploits, and he was noted not only for his bravery and his strength, but also his ability to prevail in battle when others were unable.

Unfortunately for General Lin, his luck would eventually run out when he was killed in action in 1662. In order to commemorate his service, the area where he set up his camp was officially named ‘Lîm-hōng-iâ’ with the word ‘iâ’ or ‘ying’ (營), which translates as ‘camp' or ‘barracks’ completing tne name, which is literally ‘General Lin Feng’s Camp’ in English, and it has been known that way ever since.

When the Japanese arrived in Taiwan in 1895, the memory of Koxinga, who was mixed Chinese and Japanese was utilized for propaganda purposes, and thus many of the location names that dated back to the Kingdom of Tungning Era were left untouched. The only thing that changed was the pronunciation of the Hokkien name to the Japanese pronunciation, Rinhoei (りんほうえい).

Shortly after taking control of Taiwan, one of the main development objectives for the colonial government was the establishment of a railway that would encircle the island. Planning started shortly after the first Japanese boots stepped foot in Keelung in 1895. Led by a group of western-educated military engineers, who were initially tasked with getting the rudimentary Qing-era railway between Keelung and Taipei back up and running. As the military made its way south in its mission to take complete control of the island, the engineers followed close behind surveying the land for the future railway. By 1902, the team's proposal for the ‘Jukan Tetsudo Project’ (縱貫鐵道 / ゅうかんてつどう), otherwise known as the ‘Taiwan Trunk Railway Project,’ which would have the railroad pass through each of Taiwan’s established settlements, including Kirin (基隆), Taihoku (臺北), Shinchiku (新竹), Taichu (臺中), Tainan (臺南) and Takao (高雄) was finalized and approved by the colonial government.

Construction on the railway was split up into three phases with teams of engineers spread out between the ‘northern’, ‘central’ and ‘southern' regions of the island. In just four short years the northern and southern portions of the railway were completed, but due to unforeseen complications, the central area met with delays and construction issues. Nevertheless, the more than four-hundred kilometer western railway was completed in 1908 (明治41), taking just under a decade to complete, a feat in its own right, given all of the obstacles that had to be overcome.

I’ve jumped around quite a bit in the railway construction timeline here, and I’m afraid I may end up confusing people, so I think it’s important to explain that the construction of the southern portion of the railway was completed quite early. In fact, while the government was still mulling over the proposals for the Taiwan Trunk Railway Project, construction on the railway in the south was already almost completed. The southern section, originally between Takao (Kaohsiung) and Tainan opened for service in 1900, and once that section was done, construction continued progressing north towards Kagi (Chiayi).

Interestingly, as construction on the railway progressed, in some cases, instead of constructing stations, the engineers built temporary platforms (臨時乘降場 / かりじょうこうじょう), which marked the space where a train station would eventually be constructed. The focus was to get things up and running before refining the system, which is one of the reasons why construction on the railway was able to be completed so quickly. The Rinhoei Temporary Platform (林鳳營乘降) opened for service in 1901 (明治34年), which would have been a pretty big thing for the village, despite its low population.

The temporary station, though, didn’t end up lasting very long as the First Generation Rinhoei Station (林鳳營停車場) officially opened just a year later in 1902 (明治35年). The small wooden station house that was constructed would remain in place for the next three decades prior to it being renovated and expanded in 1933 (昭和8年). Amazingly, given the number of devastating earthquakes in central Taiwan over the first few decades of the Japanese era, the First Generation station remained standing for four decades. That being said, the 1941 Chungpu Earthquake (中埔地震) ended up being the one that toppled the station, requiring the construction of an entirely new station.

Link: Taiwan’s Remaining Japanese-era Train Stations (台鐵現存日治時期車站)

The Second Generation Rinhoei Station (第二代林鳳營驛), the station we continue to enjoy today, opened for service on March 31st, 1943 (昭和45年). The design of the station was considered quite standard for its time, making use of an architectural design that became common in both Taiwan and Japan at the time. Most notably, the nearby Houbi Station (後壁車站), which also had to be reconstructed due to the earthquake, is almost exactly the same. However, it’s important to note that even though this style of architectural design, which I’ll explain in detail a little later, became the standard for smaller stations like this, when the building was constructed, funding was pretty tight, given that Japan went on an ill-fated militaristic adventure, which would ultimately end in massive defeat.

When the Japanese era came to an end and the Chinese Nationalists took control of Taiwan, the station was renamed ‘Linfungying Station’ (林鳳營車站), which as we should know by now was just the Mandarin pronunciation of the village. What’s important to note about the difference between the Japanese era and the current era is that train stations were originally designated using the Japanese word ‘eki’ (驛 / 駅 / えき) whereas they’re now referred to as ’chezhan’ (車站), which is a minor difference between the two languages.

Suffice to say, the next half century was pretty uneventful at the station, and nothing really changed until 2003, when a more than a decade-long political argument about the method of romanization used in Taiwan started. In 2002, the government adopted the ‘Tongyong Pinyin’ (通用拼音) system, which was considered an improvement on the ‘Hanyu Pinyin’ (漢語拼音) system used in China. The point was the adopt a uniform system of romanization that ended decades of variations of the Wade-Giles (威妥瑪拼音) system of romanization that made little to no sense.

From 2003 to 2009, the station’s signage was changed to ‘Linfongying’, but when the Chinese Nationalist Party won an election landslide in 2008, it was announced that Hanyu Pinyin would become the standard of romanization of Taiwan, and the signage at the station was changed again to ‘Linfengying,’ which makes more sense, at least to me.

What doesn’t make sense is that taxpayers dollars are constantly being wasted on all these romanization policy changes. You might think its not a big deal, but when you take into consideration all the signage between the Taiwan Railway, Taipei Metro, Taiwan High Speed Rail, Kaohsiung Metro, etc, there are close to five hundred public transit stations in Taiwan where money has to be spent to change these things.

Hopefully they’ll just stick with the current system.

As the railway has continued to modernize over the decades, it’s actually quite amazing that this station hasn’t been phased out, but since the turn of the century, steps have been taken to reduce the amount of funding required to keep it operational. In 2000, the station was reclassified as a Simple Station (簡易站), which meant that it would only be serviced by local commuter trains (區間車), with the various types of express trains passing by. Management of the station was transferred to the staff at the nearby Longtian Station (隆田車站), and later, the station started using electronic card swiping, reducing the need for additional staff at the station.

Today, you’re likely only going to find one or two people working at the station, whose role it is to maintain safety, keep it clean, and ensure that everything runs smoothly.

Save for some chipping paint on the exterior of the building, the station today remains in relatively good shape. At some point, though, its going to have to receive some restoration work to ensure that it can remain in operation for years to come. Fortunately, it was officially recognized as a Protected Heritage Property (保護的歷史性建築) in 2005, which means that funding has to be made available for its eventual restoration. The current station recently celebrated its eightieth anniversary, which is quite a feat in Taiwan today, but its longevity is really thanks to the community that it services.

Before I move on to detailing the architectural design of the station, I’ve put together a condensed timeline of events in the dropdown box below with regard to the station’s history for anyone who is interested:

-

1895 (明治28年) - The Japanese take control of Taiwan as per the terms of China’s surrender in the Sino-Japanese War.

1896 (明治29年) - The Colonial Government puts a team of engineers in place to plan for a railway network on the newly acquired island.

1900 (明治33年) - The first completed section of the Japanese-era railway opens for service in southern Taiwan between the port town of Kaohsiung and Tainan.

1901 (明治34年) - The Rinhoei Platform (林鳳營乘降) opens for service. Constructed simply as a temporary platform (臨時乘降場 / かりじょうこうじょう) prior to the construction of the station.

1902 (明治35年) - After years of planning and surveying, the government formally approves the Jukan Tetsudo Project (縱貫鐵道 / ゅうかんてつどう), a plan that will connect the western and eastern coasts of the island by rail.

1902 (明治35年) - The First Generation Rinhoei Station (林鳳營停車場) opens for service.

1933 (昭和8年) - The station undergoes a period of restoration and expansion.

1941 (昭和43年) - On December 17th, a massive magnitude 7.1 earthquake (中埔地震) occurs in southern Kagi and among the casualties is the original Rinhoei Station.

1943 (昭和45年) - The Second Generation Rinhoei Station opens for service, with its architectural design exactly the same as nearby Koheki Station (後壁車站).

2000 (民國89年) - The station is downgraded from a third-class station (三等站) to a simple station (簡易站) with its management being taken care of by the staff at nearby Longtian Station (隆田車站). The downgrade in status means that the station is only serviced by local commuter trains (區間車).

2003 (民國92年) - In accordance with the government’s romanization policy, the station’s name is changed from ‘Linfungying’ to ‘Linfongying’ (both of which aren’t standard pinyin).

2005 (民國94年) - Linfengyin Station is recognized as a protected heritage property (保護的歷史性建築)

2013 (民國102年) - The station is optimized to make use of card-swiping machines instead of requiring tickets, which reduces the need for staff at the station.

2016 (民國105年) - The station-front of Linfengying Station receives a complete remodel with the road approaching the station improved, and the bus station that transports the station’s passengers elsewhere is given a complete remodel.

Architectural Design

Rinhoei Station, like quite a few other train stations around Taiwan, especially those in central and southern Taiwan, is what we refer to as a ‘Second Generation’ (第二代) station. As we learned above, the first version of the station lasted almost four decades, but it eventually succumbed to an earthquake in 1941, requiring a complete rebuild. The interesting thing about this is that the original station actually lasted a lot longer than some of its contemporaries, especially those in the region between between Taichung and Tainan, most of which were rebuilt in the 1920s and 1930s.

When those stations were rebuilt, in most cases they were done quite beautifully, and as was the case during the Showa era in Taiwan (1926-1945), most of them were constructed with reinforced concrete and made use of a fusion style of architectural design that combined traditional Japanese design with elements of western design. A pretty good example of this is the Second Generation Tai’an Railway Station (泰安舊車站) in Taichung, which was reconstructed in 1937.

There are a few reasons why I mention this: The first is because when the Japanese first arrived in Taiwan, resources were scarce, and when it came to construction projects, most of the materials had to be imported directly from Japan. Thanks to the rapid development of the island, however, those materials were eventually able to be made locally, which made construction projects progress considerably faster, and the cost was considerably less.

That being said, the rebuild of Rinhoei Station came at a time when the Japanese government was strapped for cash, and the funds that would typically reserved for a construction project like this just weren’t available due to the Japanese empire’s ill-advised military adventures.

Ultimately, this station just wasn’t busy enough to necessitate one of the more costly styles of building, like the one mentioned above, but as far as I’m concerned, that’s okay. I think a small wooden station in a quiet southern Taiwanese village gives off a much much hometown kind of vibe.

When it comes to these traditional wooden station houses, by the time this one was constructed, it’s safe to say that it probably didn't take much effort in the architectural-design process. The construction staff at the Railway Bureau were already quite proficient in building them, and stations constructed in this particular design had become quite common rural areas in both Japan and Taiwan.

As mentioned earlier, though, when both Rinhoei Station and neighboring Koheki Station (後壁驛), known today as ‘Houbi Station’ were constructed, funds were tight. With that in mind, the amount of extra care that was usually taken for these buildings wasn’t available. To make a comparison, if you take a look at the more more traditional Qidu Train Station (舊七堵車站) just outside of Keelung, you’re likely able to see a very obvious difference in the attention to detail that was taken with regard to the woodwork, the windows, the roof, and the pillars that surround the building allowing for the extension of a more traditional-style roof.

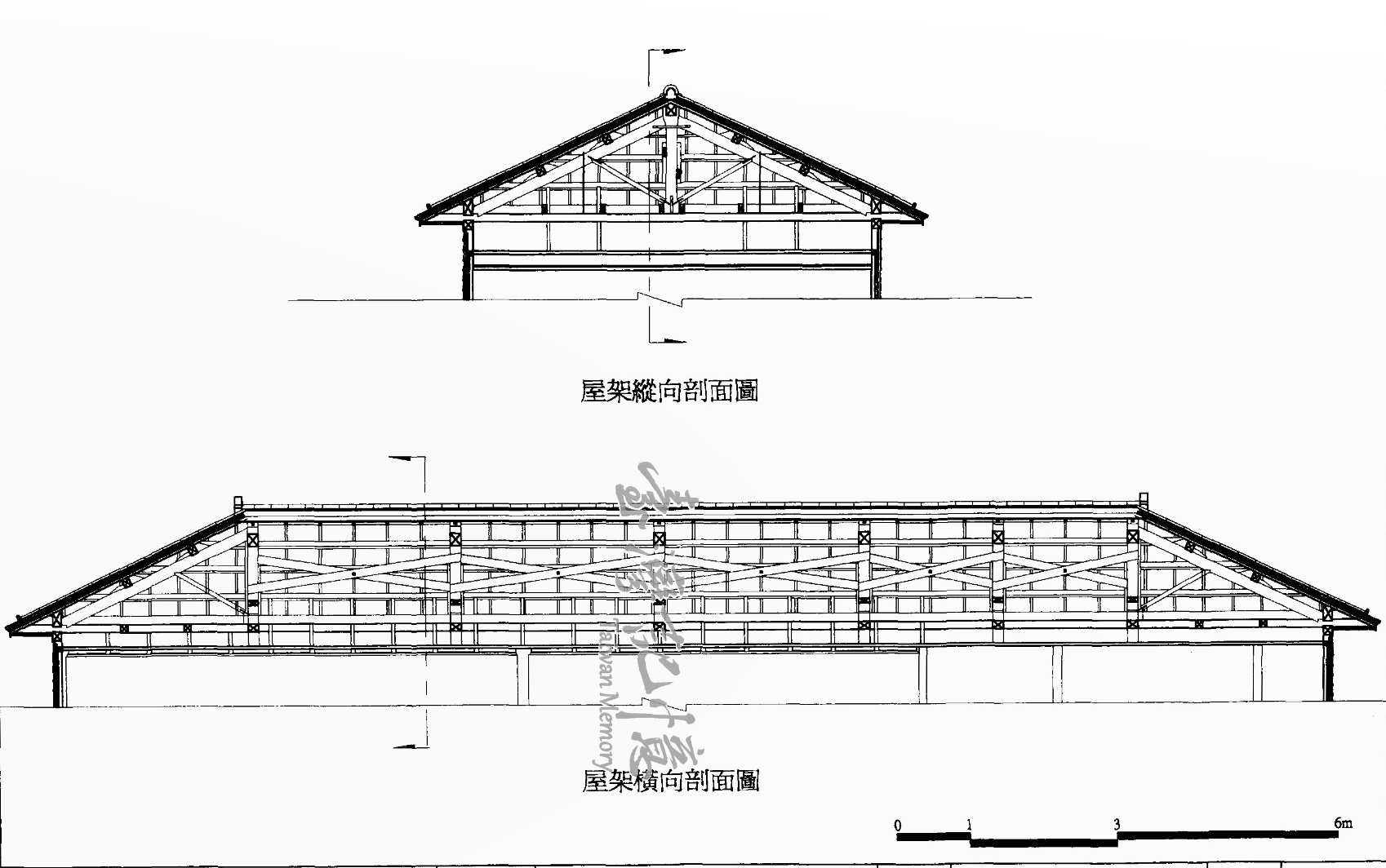

To describe the station’s architecture, let’s start with the basics: Rinhoei Station was designed using elements of Western Baroque (巴洛克建築) combined with traditional Japanese design. However, for cost-saving measures, the western elements were subdued, making the Japanese elements stand out more. The station was constructed using irimoya-zukuri (入母屋造 / いりもやづくり) style of design, most often referred to in English as the “East Asian hip-and-gable roof,” which is a translation that I have issues with.

What ‘irimoya’ actually means is that the building was constructed in a method that ensures that the building is structurally sound enough to be able to withstand the weight of a roof, which usually eclipses the size of the base. This style of design is set up to support a number of traditional Japanese-style roofs, some of which can be quite elaborate, while others, like this one are quite plain. In order to support the roof, which is usually covered with heavy tiles, the base is equipped with pillars on both the interior and exterior and are connected to a network of trusses, which allow the building to not only sustain the weight of the roof, but offer stabilization during earthquakes.

The roof was constructed using the four-sided ‘yosemune’ style (寄棟造 / よせむねづくり) of design, which is one of Japan’s more simplistic styles of architectural design, and somewhat comparable to the four-sided roofs we’re used to in western countries. With four sloping faces and two trapezoid-shaped ends. The tiles that cover the roof were replaced at some point, and although they’re still stone tiles, the original tile ends, known in Japanese as ‘onigawara’ (鬼瓦 / おにがわら) were replaced with tiles that have the words ‘fortune’ (福) on them.

When you look at the roof of this building, you’ll probably notice a pretty big difference from the other Japanese-era buildings that remain around Taiwan, because it’s about as basic as you’ll get with the architectural design of that era. It’s not particularly that impressive, but its functional, which is the most important thing, right?

Despite the simplicity of the roof’s design, like every building constructed in the irimoya-style, it eclipses the base of the building, offering protection from the elements for anyone waiting outside the station for friends and family to arrive. To assist with the stabilization, there is a series of pillars outside of the passenger-side of the building that surround the station on three sides. In the past, passengers would have been able to exit the station without actually passing through the turnstiles, but since the introduction of the e-card swiping system, that has been changed.

What hasn’t changed, though, is the extension of the roof that covers the eastern-side of the building is quite large, with a side exit that provides access to the station’s waiting room.

Once again, to make a comparison, with regard to the cost-saving measures when it came to the construction of this building, if we take a look at Bao-an Station (保安車站), south of Tainan Station, you’ll discover that there is an absence of the traditionally designed roof-covered ‘kurumayose' (車寄/くるまよせ) porch that protrudes from the flat front of the building. There’s a porch here, but it’s about as basic as you’re going to get from Japanese-era architectural design, although when paired with the roof, one of those flashy porches probably wouldn’t really mix well anyway.

Moving onto the interior, the base of the building is essentially a rectangular-shaped structure that is split into two sections, with the larger eastern side reserved for passengers, and the smaller western side used by the staff working at the station. Obviously given that the station remains in operation, there’s not much I can say about the interior of the staff section of the station as its not accessible to the public. The eastern-side of the building that’s reserved for passengers, however, is interesting, as it’s cleverly split into two sections.

From the entrance, you’ll enter the main lobby of the building where the turnstiles to the platform are directly in front of you. The ticket window and the private section of the station is directly to your left while there’s waiting lobby to the right. The passenger side is considerably larger, and features beautiful wooden benches and features beautiful Japanese-style paneled sliding glass windows (日式橫拉窗) on all four sides, which assist in providing a considerable amount of Tainan’s natural light into the interior as well as a bit of breeze on hot days. There’s also an alternate exit within the waiting lobby that previously allowed people to exit through a different set of turnstiles, but currently offers faster access to a recently constructed detached public washroom space a short distance from the building.

Within the interior of the building, there’s not all that much that you need to pay attention to, but I’d like to point out three things that some people might not realize the significance of. The first is the small wooden gate located near the ticket booth. Gates like this were once very common in train stations during the Japanese-era as a means to help filter people in and out while waiting in line, but, sadly, very few of them remain these days. The gate was originally constructed to look like the Japanese word for ‘money’ (円), but was likely replaced at some point and looks a little different now.

The second thing you’ll want to take note of is probably a little more obvious, and already mentioned above, but it’s important to note that the long wooden benches in the waiting room are originals, and even though they’ve been poorly painted over a few times, they’re quite nice, and like the wooden gate, are part of a dying breed in Taiwan’s train stations.

Once you’ve passed through the turnstiles to the platform space, you can get a pretty good look at the rear of the station, especially the roof as you climb the stairs to the overpass that brings you to the railway platform. As the railway has widened and been electrified in the decades since the station was constructed, this entire area has transformed considerably. What hasn’t changed, though, is that while you’re waiting for your train to arrive and take you away, you get to enjoy one last look at this historic station.

Getting There

Address: Linfengying #16, Liujia District, Tainan (臺南市六甲區林鳳營16號)

GPS: 23.238889, 120.320556

Whenever I write about one of Taiwan’s historic train stations, obviously the best advice for getting there is to simply take the train, and in this case, I really don’t think there’s any better option. The thing about Linfengying is that it’s pretty much in the middle of nowhere, in an awkward position just south of Chiayi Station, and several stops north of Tainan Station.

If you have your own means of transportation, you can simply input the address listed above into your vehicle’s GPS, or on Google Maps to get to the station. There’s a parking lot to the left of the main entrance of the station, so you’ll be able to park your car or scooter for a short time to go check it out.

There’s also a Youbike Station at the station with about two dozen bikes available, so if you feel like exploring the area by bicycle, you can hop on a bike and go for a ride through the village, which is mostly just farmland.

Bus

Just outside of the station, there’s a bus station that is serviced by a number of bus routes. Most of the routes head in the direction of Xinying (新營), Liujia (六甲) or Madou (麻豆), and are set up more for the local citizens than they are for tourists, so I’m not sure how much help they’ll be for the average visitor.

Trust me, you’re much better off taking the train.

Whether you look at this station with a 120 year history, or as an eighty-year old building, it’s quite remarkable that it has been able to withstand the test of time, and the constant modernization efforts made by the Taiwan Railway.

There aren’t many stations like this remaining in operation today, so if you find yourself passing through the area, you might want to stop by and check it out. It’s a part of Taiwan’s living history, and even though it’s not a major tourist attraction, it does deserve a bit of appreciation and attention.

References

Linfengying railway station | 林鳳營車站 中文 | 林鳳営駅 日文 (Wiki)

Tainan Prefecture | 臺南州 中文|台南州 日文 (Wiki)

林鳳營車站 (國家文化記憶庫)

林鳳營車站 (國家文化資產庫)

林鳳營車站 (臺灣驛站之旅)

林鳳營車站‧用心生活品出的濃醇香 (旅行途中)