Eight years ago, when I originally wrote about the Tainan Martial Arts Hall, I was still a novice at writing, and although I was quite interested in these topics, admittedly, I didn’t really know all that much. Spending the better part of the last decade researching the Japanese-era, and traditional Japanese architecture with more than a hundred articles under my belt, I figured it was probably a pretty good time to give this article an update.

Looking back, some of the things I wrote in the original article weren’t factually correct, and there was also an embarrassing lack of detail with regard to both the history and the architectural design of this iconic building, which is the grandest of all of the Martial Arts Halls remaining in Taiwan today. To solve those problems, I’ve gone ahead and deleted all of the text in the original article and have written an entirely new one in order to give this beautiful building the respect it deserves. In addition to writing an entirely new article, I’ve also taken a look at the original photos and have put some more work into them, as my photo editing skills have also improved in the years since I first published this article.

As part of my ongoing project to improve some of the older content on my blog, I’ll be giving some extra attention to some of my older articles about Taiwan’s historic Martial Arts Halls in order to better tell their stories. Thankfully, even though rewriting these articles takes a considerable amount of time away from my long list of other places to write about, it also helps me keep up with everything that’s happening with these halls as the list of Martial Arts Halls that have been restored and opened up to the public continues to grow, with another two or three of these historic buildings expected to make an appearance within the next year or two.

Something I’ll never need is an excuse to take a trip to Tainan, which is (and always will be) one of my favorite places to visit in Taiwan. I have a long list of places in the city to visit and take photos of, and since my last visit, that list has grown a lot longer thanks to the hard work of the city’s Cultural Affairs Bureau, which has invested a considerable amount of time and money into the restoration of the city’s remaining Japanese-era places of interest. One of those restoration projects that I’ve been keeping a keen eye on is the historic Tainan Prison Martial Arts Hall (臺南刑務所演武場), which should be completely restored and reopened in the near future.

Although Tainan is widely known as one of the nation’s most historic cities, it has given itself something of a facelift in the years since I originally wrote this article. Today the city not only prides itself on its historic attractions, but it has also become an important hub for the youth of Taiwan to put their skills on display with hip new restaurants, cafes, cocktail bars, art galleries, etc. Within walking distance of the Tainan Martial Arts Hall, you’ll not only find the Confucius Temple and the Grand Mazu Temple, but you’ll also find a few of the best cocktail bars in the country, and a plethora of hard-to-reserve restaurants that celebrate the history of this beautiful town.

If you’re planning a trip to Tainan, there’s obviously a lot to see and do, and visiting has been made even better by a concerted effort by the city government to promote English-language accessibility for International tourists at tourist destinations, restaurants and shops - something that should help out quite a bit. That being said, despite their best effort, the English-language information available about some of the city’s most important attractions remains somewhat limited, or at least, basic. Although, I guess I should probably also mention that most of the time Chinese-language info is also quite limited. So, if you’re planning a visit to the city and would like to check out the Tainan Martial Arts Hall, look no further, I’m going to provide an information overload!

Below, I’ll introduce the history of this Martial Arts Hall and it’s architectural design, two things that I didn’t really explain very well in my original attempt at writing about the building. Before I start, though, if you haven’t already, I recommend stopping here and first reading my introduction to Taiwan’s Martial Arts Halls, which provides an explanation of the purpose of the buildings, their history and where else you’re able to find them around the country!

Link: Martial Arts Halls of Taiwan (臺灣的武德殿)

If you’re up to date with all of that, let’s just get into it!

Tainan Martial Arts Hall (臺南武德殿)

I’ll start with one important fact regarding the Tainan Martial Arts Hall - This is one of the only two remaining ‘Prefectural Level’ Martial Arts Hall in Taiwan today, and its history also makes it one of the oldest in the country.

The key thing to remember here is that as a prefectural level building, it served as the headquarters of all the Martial Arts Halls in the Tainan area, which in turn meant that it was the largest and grandest of them all. However, even though it’s often referred to as one of the ‘oldest’ in Taiwan, that’s not necessarily the case, which is why I need to do a bit of explaining so that you can better understand it’s complicated history.

In my article about the Martial Arts Hall of Taiwan linked above, I explained that in 1895 (明治28年), the same year that the Japanese took control of Taiwan, the ‘Dai Nippon Butoku Kai’ (大日本帝國大日本武德會) was formed in Japan. Translated literally into English as the “Greater Japan Martial Arts Society,” the organization held strong ties to Japanese government, and many of its instructors were former samurai, tasked with bringing martial arts training to the general public.

These days, taking up any Martial Arts discipline is pretty cool hobby, and part of my personal interest in the subject is due to my many years of studying Tae Kwon Doe back in Canada. During the Meiji-era in Japan however, the political climate was a lot different than today, and martial arts education was meant more as a propaganda tool to fuel nationalism and militarism.

With its headquarters located in the cultural capital of Kyoto (京都), Martial Arts Halls slowly started popping up all over Japan, and by 1900 (明治33年), they started appearing here in Taiwan as well. The first three constructed in the Japanese empire’s new colony were located in the capital of Taihoku (臺北), Taichu (臺中) in central Taiwan, and Tainan (臺南) in the south.

This is where some of the problems arise with regard to the literature about the Tainan Martial Arts Hall, and admittedly, I fell for some of that lack of clarity in my first attempt at writing about the hall. Taking a look at the name used to refer to the Tainan Martial Arts Hall today, it is best translated literally as ‘The Original Tainan Martial Arts Hall’ (原臺南武德殿), so a lot of people end up thinking that it was the first hall in town.

In fact, the building that we’re able to visit today is actually the ‘Second Generation Tainan Martial Arts Hall’ (第二代臺南武德殿), which means that although it’s quite large, it’s not as old as some of the literature insists. Unfortunately, another reason why the resources regarding the hall can be confusing is because there is very little credible information regarding the history of the original.

What we do know is that the First Generation Tainan Martial Arts Hall was constructed in the Saiwaichō (幸町 / さいわいちょう) neighborhood of the city, which was a short distance from the railway station. Essentially the governing district of Tainan Prefecture, the area near the original Martial Arts Hall was home to the Tainan Prefectural Hall (臺南州廳), Tainan City Hall (臺南市役所), Tainan Prefectural Police Bureau (臺南警察署) and the Tainan Confucius Temple (臺南孔廟).

In today’s terms, the original hall was situated on the eastern side of the traffic circle where Tang Te-chang Memorial Park (湯德章紀念公園) is currently located. Today, you’ll find the Tainan City West Central District Office (台南市中西區公所) standing on the land where the original was once located. The area does however retain some of its Japanese-era charm with a number of the original buildings constructed for the governing district remaining in place.

From the few historic photos of the First Generation Hall that can still be found, it was a relatively small building, similar in architectural design to the Daxi Martial Arts Hall in Taoyuan, which itself was quite low on the hierarchy of halls. However, something that I’ve learned over the years is that when the Japanese arrived in Taiwan, a large number of the official buildings that were initially constructed by the government were more or less deemed as temporary in nature. Once the infrastructure was in place around the island to start constructing more suitable and permanent buildings, the originals were either torn down or repurposed. In fact, the original Taipei and Taichung Martial Arts Hall were eventually replaced by much larger Second Generation Halls as well.

Over the first few decades of the Japanese era a number of Martial Arts Halls were constructed around Taiwan, coinciding with the growth of Taiwan’s towns and cities, but as the political climate became increasingly militaristic, the brass at the headquarters in Kyoto issued a directive to Taiwan’s Governor Generals Office to assist in providing funding for the establishment of Martial Arts Halls around the island. Thus, the 1930s essentially became the most important years with regard to the establishment of these halls across Taiwan.

The directive insisted upon a hierarchy of Martial Arts Halls to be constructed at the village and borough level (分會), town and city level (支所) and at the prefectural level (支部), all of which would report to the headquarters branch in Taipei. In most cases, construction on the Martial Arts Halls started from the top down with those of the Prefectural Level (州廳) constructed first, but this posed a problem in Tainan as the existing building was clearly not sufficient. So, in the early 1930s, plans were drawn up by the Tainan Prefecture Civil Engineering Team (臺南州廳土木營繕組設計) for a project that would move the Martial Arts Hall from its original location to another plot of land nearby.

Located in the space between the Tainan Confucius Hall (臺南孔廟) and the Tainan Shinto Shrine (臺南神社/たいなんじんじゃ), the construction of the new Martial Arts Hall would coincide with an expansion project at the Shinto Shrine, which suffered from similar (lack of ) size issues. Construction on the Second Generation Martial Arts Hall started in February of 1936 (昭和11年), and amazingly, given the size of the building, was completed just eight months later. While it may seem like somewhat of a rush, the official opening ceremony for the building was meant to be part of a much larger schedule of events in the city that coincided with the completion of the Shinto Shrine’s expansion project, and the enshrinement of the God of Military Arts (武神鎮座祭 / ぶしんちんざまつり) at the shrine.

The new building was officially known as the “Tainan Branch of Tainan Prefectural Branch of the Taiwan Butokuden Branch of the Dai Nippon Butoku Kai” (大日本武德會臺灣分部臺南州廳臺南支部), and as mentioned above was strategically located within Tainan’s governing district of Saiwaichō, making it an important propaganda tool for the Japanese.

With that in mind, it’s important to note that the very year the Martial Arts Hall was completed, the infamous “Kominka” (國民精神總動員運動) policy came into effect in Taiwan.

Often referred to in English as ‘Japanization’, the basic translation of the policy’s name meant to “make people become subjects of the empire”, which was essentially just forced assimilation. After the policy came into effect, the government enforced strict language policies, required citizens to take Japanese names, instituted the “volunteers system” (志願兵制度), drafting Taiwanese into the Imperial Army and required locals to take part in Japanese cultural and religious activities, including visiting Shinto Shrines and of course, learning Martial Arts.

Link: Japanization | 皇民化運動 (Wiki)

Interestingly, after the Second Generation Martial Arts Hall opened, the original hall continued to be used by the local police, who for a period used the exterior of the building as a shooting range. Later, the Tainan Historical Museum (臺南史料館) took up residence within the building, but given its proximity to the Prefectural Hall and other governmental institutions, it was heavily damaged during American bombing runs in the latter stages of the Second World War. In the post-war era, the space was occupied by the Tainan City Reserve Command (臺南市團管區司令部), but then much later became the site of the Tainan City Central District Office (臺南市中區區公所), which continues to occupy the space today.

\Despite the rush to complete the construction of the building, once it was open, it was often referred to as the ‘most beautiful Martial Arts Hall in Taiwan’ (台灣第一演武場), and that’s probably one of the reasons that it wasn’t torn down like the hundreds of other Martial Arts Halls that were constructed around Taiwan. Suffice to say, the building was completed in 1936, and the Japanese Colonial Era came to a conclusion in 1945 (昭和20年), when the Japanese were forced to surrender control of Taiwan.

As a Martial Arts Hall, it lasted less than a decade.

In the post-war era, the building initially became home to the Tainan City Middle School (臺南市立中學), which was located primarily within the basement of the hall. Then, when Chiang Kai-Shek and the Chinese Nationalists fled to Taiwan in 1949, they brought with them almost two million Chinese refugees. The influx of new students meant that the space within the hall was insufficient, so the school exchanged campuses with an elementary school, which eventually became Zhongyi Primary School (忠義國民學校). Ultimately, the number of students that attended the elementary school far exceeded the available space within the hall, so they constructed a new building next to the Martial Arts Hall on the grounds that were once occupied as part of the Shinto Shrine. With most of the classes migrating to the newly constructed school, the Martial Arts Hall became the school’s auditorium and assembly hall, and has stayed that way for the past half century.

Finally, in 1998 (民國87年), the Martial Arts Hall was registered as a Tainan City Protected Historic Property (市定古蹟), which meant that public funding would have to be made available to keep the building in good shape. A few years later in 2005, the building underwent a two year period of restoration, but today it continues to remain an integral part of the elementary school, which limits what the city can do with the building as a tourist attraction. The good news is that the Martial Arts Hall continues to serve as a space for practicing martial arts, and it is open to the public on weekends, but if you visit during the week you likely won't be able to see the interior. The reason for this is actually quite understandable given that the building continues to be used primarily by the school as an auditorium for performances, gym class and school activities. Nevertheless, it does act as a popular tourist destination given that it sits next to Taiwan's first Confucius Temple (台南孔子廟), the recently revitalized Hayashi Department Store (林百貨) and the hip Fuzhong European-style Pedestrian Street (府中街) that is full of cute little coffee shops and bistros as well as vendors selling local crafts.

Below, I’ll provide a brief timeline of events with regard to the Martial Arts Hall before I move on to describing its architectural design.

Tainan Martial Arts Hall Timeline

1895 (明治28年) - The Japanese Colonial Era begins here in Taiwan and the ‘Dai Nippon Butoku Kai’ (大日本帝國大日本武德會) was formed in Japan in order to instruct ordinary citizens in the various Japanese Martial Arts disciplines.

1900 (明治33年) - The first Martial Arts Halls start to appear in Taiwan with branches in Taipei, Taichung and Tainan.

1906 (明治39年) - The Taiwan Branch of the Dai Nippon Butoku Kai is officially established. (大日本武德會臺灣支部) with its headquarters (大日本武德會臺灣本部) located within the Taipei Martial Arts Hall

1920 (大正9年) - A governmental directive is made to construct Martial Arts Halls in each of Taiwan’s prefectures, towns, villages and boroughs.

1936 (昭和11年) - Construction on the Second Generation Martial Arts starts in February with much of the work completed by October. The official opening ceremony was held on October 24th and coincided with the consecration of the expansion of the Tainan Shinto Shrine.

1936 (昭和11年) - The Colonial Government’s “Japanization” or ‘forced assimilation’ Kominka (皇民化運動) policy comes into effect in Taiwan.

1945 (昭和20年) - The Second World War comes to a conclusion and Japan is forced to surrender control of Taiwan.

1946 (民國35年) - Tainan City Middle School (臺南市立中學) was established within the Martial Arts Hall.

1949 (民國38年) - Chiang Kai-Shek and the government retreat to Taiwan and bring with them several million refugees displaced by the Chinese Civil War.

1953 (民國42年) - Due to insufficient space, Tainan Middle School moves out of the former Martial Arts Hall to another campus, exchanging space with another school that changed its name to Tainan City Central District Zhongyi National Primary School (臺南市中區忠義國民學校).

1968 (民國57年) - The Martial Arts Hall becomes the auditorium for Zhongyi Elementary School, which constructed a new campus next to the Martial Arts Hall, but some classes remain in the basement of the building.

1998 (民國87年) - The Martial Arts Hall is registered as a Tainan City Protected Historic Property (市定古蹟).

2005-2007 (民國94-96年) - The Martial Arts Hall underwent a two year period of restoration repairing the roof, ceiling, floors, windows, plumbing and electricity.

Architectural Design

Historians in Taiwan generally agree that the Daxi Butokuden (大溪武德殿) is the most well-preserved of the handful of Martial Arts Hall that remain in Taiwan today, but the Tainan Martial Arts Hall is the grandest of them all. As one of the only remaining Prefectural Level Hall, the building is considerably larger than all of the other remaining Martial Arts Halls in Taiwan today, and its size is likely one of the main reasons why it has been able to escape being torn down like so many of its contemporaries.

Similar to the other Martial Arts Halls that I've written about thus far, the Tainan Hall was a product of its times, constructed during the Showa era with a fusion of Japanese and Western construction techniques mixing brick, concrete and beautiful Taiwanese cypress. However, where this particular building stands apart from its contemporaries is in its scale. Not only is it the largest remaining Martial Arts Hall in Taiwan, it’s also the only one that has multiple levels. In most cases, Taiwan’s Martial Arts Halls were designed to be elevated off of the ground in order to have their iconic spring floors installed, but this one is different in that it consisted of multiple levels with the springs loaded in a space between the upper floor and the ceiling of the basement.

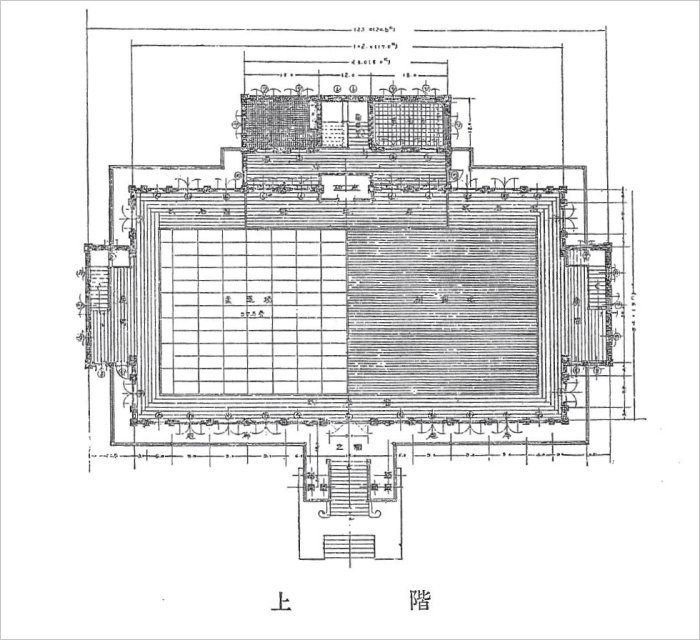

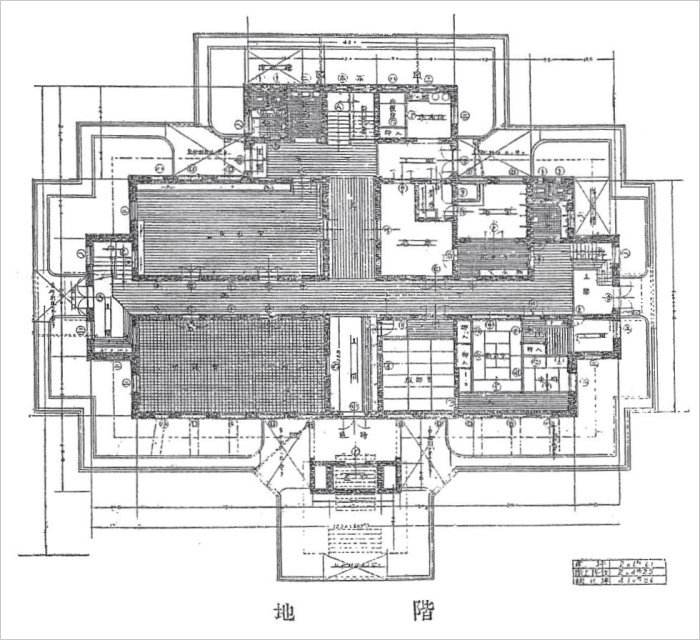

The ground level of the building was initially used primarily for office and classroom space in addition to providing changing rooms for people taking part in classes. The second floor on the other hand was dedicated solely to the practice of martial arts and offered significantly more floor space for classes than any of the others.

In what is probably confuses most people, the building is officially listed as ‘four bays wide and four bays in length’ (左右各面寬四開間), which means that it is about 661㎡ (200坪) in size. The ‘bays’ (開間) measurement is an old style of measurement that you won’t see mentioned very often in Taiwan these days, but when it comes to Tainan, most of the places of worship and other historic buildings are still measured in bays, which are about 3.6 meters in length.

Admittedly I only know about these measurements because I recently just finished writing an article about the historic Grand Mazu Temple (臺南大天后宮), which is close to the Martial Arts Hall.

To give you an idea of the size of the building, the Martial Arts Hall in nearby Xinhua is 238㎡ (72坪) in size while the next largest in Taiwan, the Changhua Martial Arts Hall is 390㎡ (118坪).

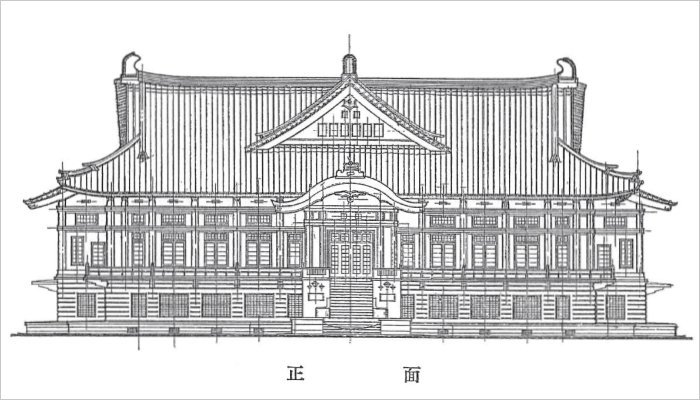

Given that this was a Prefectural Level Martial Arts Hall, there are quite a few finer details in the architectural design that make the building stand apart from the others you can see in other areas around Taiwan, but it’s probably easier to start describing some of the design basics that it shares with the others. To start, Taiwan’s Martial Arts Halls were all designed in what should be considered traditional Japanese architecture, but it’s important to note that this style of architectural design was heavily influenced by the architectural style of the Tang Dynasty (唐朝) in China. You’ll find quite a few elements in its design that imitate that of a Tang palace and no where is that more obvious than in the design of the roof, which is characteristic of Tang-style architecture. Obviously, the roof remains very much 'Japanese' in design, but it’s important to note that the architectural style is a nod to Japan's historic relationship with China.

Having been in control of Taiwan for over four decades prior to it’s construction, all of the infrastructure was in place to ensure that the building could be constructed quickly and efficiently, and like all of the other Martial Arts Halls that were constructed during the Showa-era, the Tainan Hall was built with a combination of Japanese and Western construction techniques mixing brick, concrete and beautiful Taiwanese cypress that ensured the structural stability of the building. Known as east-west fusion (和洋混和風建築), this particular style of fusion design was popular with the Japanese architects at the time, who expertly blended traditional architectural design with modern western construction techniques. More importantly, the fusion design became essential in the colonial government’s building standards code as modern construction techniques helped to ‘earthquake proof’ buildings, something the Japanese authorities learned the hard way over their fifty years of controlling Taiwan.

In another similarity with the other Martial Arts Halls around the island, the Tainan Hall was constructed using the ubiquitous irimoya-zukuri (入母屋造 / いりもやづくり) layout. The most important thing to keep in mind about this design is that the ‘moya’ (母屋 / もや), which is literally translated as “mother house” is considerably smaller than the roof above it - In most cases with this style of design, the weight of the roof is stabilized by a network of pillars and trusses within the ‘moya’ or the base that help to distribute its weight. However, thanks to the modern construction techniques and the concrete base, the building is easily able to sustain the weight of the roof, which is the largest and most elegant of all of the remaining Martial Arts Halls in Taiwan. Another area where the concrete base helped with the decorative elements of the building’s design is with regard to the large rectangular sliding windows that the designers were able to add to all four sides of the ‘moya’, which allowed for a considerable amount of natural light and fresh air into the martial arts space during the day.

Link: Irimoya-zukuri (JAANUS) | East Asian Hip-and-Gable Roof (Wiki)

As the building was constructed in the irimoya-style, it goes without saying that it also features a hip-and-gable roof (歇山頂) as they more-or-less go hand in hand with each other. Keeping in mind that it was a high-level Martial Arts Hall, the design of the roof is a lot more grand than what you’d see with some of the others around Taiwan and is probably better compared, at least in its decorative elements, with what you’ll see at either the Taoyuan Shinto Shrine or the Puji Buddhist Temple in Taipei.

Within traditional Japanese architecture, there are a number of styles of roof design that fall under the ‘irimoya’ category, but those most commonly utilized in the construction of Taiwan’s Martial Arts Halls were a combination of the two-sided kirizuma-zukuri (切妻造 / きりづまづくり) and the four-sided yosemune-zukuri (寄棟造 / よせむねづくり), which work together to create a curvy design. To explain both of these terms in a simple way, the lower ‘yosemune’ section is the four-sided ‘hip’ section of the roof that both covers and extends beyond the base. The upper ‘kirizuma’ section is a two sided sloping ‘gable’, which is likened to an open book, or the Chinese character “入” which faces toward the front and rear of the building.

On all four sides, the hip slopes at a downward angle and eclipses the base of the building by several meters. On the top section, the two-sided sloping gable is shorter in length in the front than it is on the rear, where it extends well beyond the base of the building. The interesting thing about this fusion roof design is that it plays somewhat of an optical illusion on whoever is looking at it as the upper-section appears smaller than the lower section, but in actuality covers the entirety of the ‘moya.’ This allows the lower area of the roof to extend well beyond the perimeter of the building while also distributing the weight evenly to ensure structural integrity.

Adding to the complexity of the roof’s decorative elements, you’ll find triangular ‘chidori hafu’ (千鳥破風 / ちどりはふ) dormer gables on both the northern and southern sides of the roof. Decorative in nature, the gables also play a functional role in that (in this case) they feature windows that allow for even more natural light into the interior of the main hall. That being said, this is a style of architectural roof design that is most associated with castles back in Japan, which goes to show that they spared no expense in ensuring that the building stood out from the rest.

Another area where the roof of the Martial Arts Hall differs from almost all of the other remaining halls in Taiwan is that it features what are known as ‘shibi’ (鴟尾 /しび) on the two ridge-ends. Meant to symbolize ‘protection’, these ornaments are curved to look like the end of a birds tail and like many other elements of the roof, this is a common architectural design that you’ll find within places of worship and castles in Japan.

Unfortunately, by this point most of you are probably already a bit confused by all of these terms, and it is difficult to actually explain each of these parts in an easy to understand way, so I’ve designed a helpful diagram that should help illustrate and help you better understand what I’m trying to explain here.

Hiragawara (平瓦 /ひらがわら) - A type of arc-shaped clay roofing tile.

Munagawara (棟瓦 /むながわらあ) - Ridge tiles used to cover the apex of the roof.

Shibi (鴟尾 /しび) - ornamental ridge-end tiles that are used to symbolize protection.

Nokigawara (軒瓦/のきがわら) - The roof tiles placed along the eaves lines.

Noshigawara (熨斗瓦/のしがわら) - Thick rectangular tiles located under ridge tiles.

Sodegawara (袖瓦/そでがわら) - Cylindrical sleeve tiles

Tsuma (妻/つま) - The triangular-shaped parts of the gable on the roof under the ridge.

Hafu (破風板/ はふいた) - Bargeboards that lay flat against the ridge ends to finish the gable.

Working in tandem with the design of the roof, the Martial Arts Hall features a beautiful karahafu porch (唐破風 / からはふ), which is essentially an elaborately designed covered entrance that opens up to the main doors of the hall. The ‘hafu-style door’ is a popular addition within traditional Japanese architectural design, dating back to the Heian Period (平安時代) from 794-1185. However, it’s important to note that like the triangular gables mentioned above, these hafu-porches are most commonly associated with castles, temples, and shrines, so its inclusion here gives the Martial Arts Hall more prestige in its decorative design.

The covered roof section of the porch in this case was designed in the nokikarahafu (軒唐破風 / のきからはふ) style, which means that it flows downward from the top-center with convex-curves on each side. With the triangular Chidori Hafu gable just above the porch, these two decorative elements create a flowing effect that makes the roof stand out even more.

Moving onto the interior of the building, it’s important to remind readers that while much of the exterior has remained the same since 1936, the interior on the other hand has gone through considerable alterations to fit the needs of the school that occupies the space today. It’s also important to note that even though the Martial Arts Hall is open on weekends for public visits, the lower sections that are part of the school aren’t made available, which means that I won’t have photos from that area. That being said, my visit to the interior of the building wasn’t (technically) during the official opening hours, so when I did enter the building, I did so from an open door in the basement, so I do have a bit of an idea of what it looks like down there.

Starting with the upper level, the large open room was essentially split into two sections with half reserved as a space for Judo (柔道場) and the other for Kendo (劍道場). Both sides would have featured the same hardwood spring floor (彈簧地板), which would have allowed the floor to better absorb the shock of people constantly being thrown around. Located in the center-rear of the room (directly facing the front door) you would have found a small space reserved for a shrine (神龕), and likely some decorative additions that would have been related to Martial Arts or the word “budo” (武道), in addition to any trophies or awards that were won by members of the dojo. One of the areas that sets the interior space of this Martial Arts Hall apart from the others though is that the shrine area isn’t placed directly against the back wall. In this one, you can walk behind the shrine where you’ll reach a set of stairs that will bring you downstairs. Likewise, on both the eastern and western sides of the hall, you’ll find more stairwells leading to the basement.

Looking up, the ceiling is completely open and we are treated to a view of the intricate network of trusses that help to ensure that the heavy roof is held in place. With the addition of the triangular gables on the northern and southern sides of the building, there should be some beautiful natural light coming from the ceiling, so you should get a pretty good view of what’s going on. That being said, one of the recent restorations of the building included the addition of ‘modern’ trusses to replace some of the older ones.

Currently, the space is used as an auditorium for the elementary school and although it remains a large open space with beautiful hardwood floors, they’ve added a large red curtain on one end with a stage, which blocks a quarter of the natural light that could have come into the room.

Moving onto the lower level, comparing the original blueprints to the current blueprints, the partition of much of the space has remained the same with regard to the layout and the halls within, but what you’ll find within each of the rooms has changed significantly. For example, the changing rooms and locker spaces for the people practicing Martial Arts in the building has become space for music classes. The bathroom spaces have largely remained the same, but they have since been modernized to fit the needs of the school.

Nevertheless, despite all the changes within the interior of the building, one important thing remains the same: Today the Tainan Martial Arts Hall retains its role as an important space for learning martial arts and even though it remains an integral part of the elementary school, it is open to the public on weekends, and if you arrive at the right time, you might be lucky enough to see some people practicing Judo or Kendo, just like they would have done over nine decades ago.

Getting There

Address: #2 Section 2, Zhongyi Road, Tainan City (臺南市中西區忠義路二段2號)

GPS: 22.990634, 120.20364

Located within Tainan’s historic West-Central District’s (中西區) Chihkan Cultural Zone (赤崁文化園區), which is home to the famed Chihkan Tower (赤崁樓), the God of War Temple (武廟) and a ton of amazing restaurants that focus on local cuisine. The Tainan Martial Arts Hall is a short walk from quite a few of the city’s most important tourist destinations, including the Tainan Confucius Temple (台南孔廟), Grand Mazu Temple (大天后宮), the Koxinga Shrine (延平郡王祠), the Taiwan Prefectural City God Temple (臺灣府城隍廟), Shennong Street (神農街), etc.

If you weren’t already aware, Tainan is a very walkable city and every street and alley you pass by features an incredible amount of local history. You could easily drive a car or a scooter around town, but you’d really be missing out on a lot of the city’s charms. My best recommendation for getting around, if you’ve got your own means of transportation is to simply find a parking spot and from there enjoy the city on foot. That being said, Tainan is as modern as it is historic, so there are a number of public transport options for getting around the city.

Walking

The best point of reference for getting to the Martial Arts Halls is to use the Confucius Temple as the north star, which is fortunately very accessible via the city’s various methods of public transportation. Personally, if I was just arriving in Tainan via the train or an inter-city bus, I’d probably just walk there directly as the Martial Arts Hall is a short distance from the train station. That being said, most people aren’t going to Tainan solely to visit the Martial Arts Hall. That being siad, it doesn’t really matter where you start out from as the hall is in a prime location within the historic area of downtown Tainan, so if you’re staying in that area, you shouldn’t have any problem finding it if you input the address provided above into Google Maps.

High Speed Rail / Train

If you’ve arrived in the city by way of the High Speed Rail, you have a couple of options for getting to the area. First, you can take the free HSR Shuttle Bus to Tainan Train Station (台南火車站) and from there making use of any of the public transportation options listed below.

Public Bus

There are three bus stops within the vicinity of the Martial Arts Hall and the Confucius Temple, so you have quite a few options for taking a bus from wherever you are. There are far too many buses that service each of these three stops, so instead of linking to each of them below, I’m just going to provide a Google Maps link to each of the stops which will provide the list of routes and allow you to figure out which one is best for you.

Zhongyi Road Stop (忠義路站)

Shared Bicycles

Unlike many of Taiwan’s other cities, Tainan has yet to succumb to the popular Youbike shared bicycle rental service. The city is sticking to its own ‘Tbike’ (臺南市公共自行車) service, and travelers can easily access the system with their EasyCard, iPass, iCash or credit card. But you’ll have to register your card at one of the kiosks around the city before taking off.

Link: T-Bike Rental Information (Tbike)

There are three docking stations located within a short walking distance of the Martial Arts Hall where you’ll be able to pick up or return one of the bikes. As is the case with each of the bus stops above, I’ll provide a link to the location of each of the docking stations in the area on Google Maps below. If you’ve just arrived in Tainan on the train, you can easily grab one of the bikes in front of the station and make your way over to the hall, which will probably take you less than five minutes.

The closest T-Bike Stations to the Martial Arts Hall are as follows:

Taiwan Museum of Literature Station (臺灣文學館站站)

Tainan City Museum of Arts Parking Lot (臺南市美術館站)

Koxinga Shrine Station (延平郡王祠站)

Car

Finally, if you’re driving a car, there are several parking lots nearby where you’ll be able to park your car and make your way to the Martial Arts Hall. Mind you, parking within this part of town is going to be a little more expensive than other parts of the city given that the area is a popular tourist area. The parking lots closest to the hall are as follows:

You-ai Street Parking Lot (友愛街機車停車張)

Tainan City Museum of Arts Parking Lot (臺南市美術館1館停車場)

Hongsui Construction Parking Lot (竑穗建業停車場(直線距離)

For most people, the Tainan Martial Arts Hall is probably best viewed from the exterior and given that it sits next door to the Confucius Temple, it’s likely that almost everybody who visits Tainan will see it at some point. Whether or not you decide to investigate further is up to you, but even if you’re just walking by, this majestic building from a long-gone era of Taiwan’s modern history is sure to impress. You don’t get to see traditional Japanese buildings of this size too often in Taiwan these days, so you should at least take a few minutes to enjoy the view of the building before making your way elsewhere. On the other hand, if you’re visiting the city on a day when the hall is open to the public, why not take a few minutes to walk inside and check it out? There are a lot of historic places of worship for you to visit in the city, but this building is a bit different and its history is an aspect of Tainan’s history that is just as important!

References

台南武德殿 (Wiki)

臺灣的武德殿 (Wiki)

Tainan Prefecture | 臺南州 | 臺南市 | 幸町 (Wiki)

武德會與武德殿 (陳信安)

失而复得的大唐建筑-台湾武德殿 (Willie Chen)

台灣武德殿發展之研究 (黃馨慧)

武德殿研究成果報告 (高雄市政府文化局)

原臺南武德殿 (國家文化資產網)

A Study of Spatial Hierarchy of Martial Arts Halls in Taiwan (Yu-Chen Sharon Sung, Liang-Yin Chen)

台南市市定古蹟「原台南武德殿」修護工程工作報告書 (臺南市政府)

台南市市定古蹟「原台南武德殿」調查研究與修護計畫 (臺南市政府