Walking through the recently restored Datong Police Precinct, it’s difficult not to respect the architectural beauty of the building. Like many of the places that I write about these days, it was constructed during the island’s five-decade long Japanese Colonial Era, and even though it was simply one of several police stations constructed in the capital, compared with contemporary stations, it seems like they put a little extra love into its design that is unparalleled these days.

However, while I was walking through the building and taking photos of its stunning architectural beauty, I came across an elderly volunteer, who found it interesting that a foreigner was visiting the building. After the typical awkward introductions in English, there was a sigh of relief when I let him know that I speak Mandarin. These encounters with (talkative) elderly volunteers have become common for me in recent years, and although it’s nice to chat with them (and learning from them) from time to time, I’m usually on a tight schedule trying to take photos, so I try to keep conversations short. Nevertheless, in this case, the volunteer had some things that he wanted to get off his chest, and likewise had some things to show me that I wouldn’t have otherwise noticed.

I was simply there just to take photos of the beautiful Japanese-era architecture, but what I got was a quick crash course on why this historic police precinct was ‘re-born’ as the “New Cultural Movement Memorial Hall,” which is ultimately a sad story about the struggles of the past eight decades of Taiwan’s history.

The elderly volunteer explained that when the Japanese constructed the building in the late stages of their control of Taiwan, the situation around the capital was quite stable. The building came complete with jail cells, but the crime rate was pretty low, so it was mostly used as a place for drunken and disorderly members of society after a night out on the town. Obviously, I’m sure that’s a rose-colored glasses version of history, but the point he was making was to differentiate the Japanese-era experience with what came afterwards.

Pointing at one of the walls in the the jail cell, the elderly volunteer asked me to take a look at words that were etched into the concrete that read: “Down with the Republic of China” (打到中華民國), something that was intentionally left there when the building was restored. The volunteer then ushered me to the other side of the room where he showed me what looked like a water tank, but was actually a torture device known as a water dungeon. Noting that the device was used rather extensively to torture political prisoners during the White Terror (白色恐怖) era of repression from the late 1940s to the 1980s.

Quickly realizing that my photo excursion to this historic building was turning into a learning experience, it became obvious that the elderly volunteer had a lot to say about the subject, but it was also quite clear that as a resident of the area, he also lived through much of the political repression that the people of Taiwan suffered after the arrival of the Chinese Nationalists.

This building wasn’t simply just another one of the pretty Japanese-era buildings that I frequent, it was one with a very dark history. One of the ‘historical sites of injustice’ (不義遺址), a collection of sites brought back to life to help people better understand the historic injustices suffered by generations of Taiwanese, destinations like this police station highlight the struggles of those who helped to bring about the end of Martial Law, and the nation’s transition into one of the region’s most vibrant democracies.

Link: Why People Are Flocking to a Symbol of Taiwan’s Authoritarian Past (Amy Chang Chien, John Liu and Chris Horton / NY Times)

In this article, I will introduce the history and architectural design of the historic police station, but I’ll also spend time introducing the purpose of the memorial hall that occupies the space today. Suffice to say, memorial halls like this are important for realizing transitional justice, and recognizing the crimes of the past while also helping educate younger people about the history of their nation so that they can forge ahead and continue on the road to helping Taiwan become a freer and fairer country.

North Taipei Police Station (臺北北警察署)

When the Japanese arrived in Taiwan in 1895 (明治28年), the capital was nothing compared to what we’re used to today. Taipei, or what became known as “Taihoku” (台北市 / たいほくし) was a walled area that was about five-kilometers in length accessible by the East Gate (景福門), North Gate (承恩門), West Gate (寶成門) and the South Gate (麗正門). For the Japanese, the confined area within the city was far too small given their plans for the future, so they quickly got to work on pulling down the walls and developing the city.

Where one might become slightly confused is that police service in the city was initially divided between the ‘northern’ and ‘southern’ sections of the city, which at the time wasn’t actually that large of an area. The ‘Southern Police Precinct’ (臺北南警察署) was constructed close to where the ‘North Gate’ is located, and the original Northern Police Precinct (臺北北警察署) was located in Dadaocheng, the most commercially prosperous area of the capital. Geographically, this makes sense, but if you’re not really familiar with the city’s historic set-up, you might find the naming somewhat baffling in that the ‘Southern Police Station’ was located next to the ‘Northern Gate.’ The simple answer here is that prior to the arrival of the Japanese, the northern section of the city only extended to the North Gate area, growing exponentially since then.

As the capital grew in both area and population, both the north and south stations became far too small for the purpose they served, so starting in 1929 (昭和4年), the second generation South Taipei Police Station was constructed, and then four years later in 1933 (昭和8年), the Taipei North Police Station was completed.

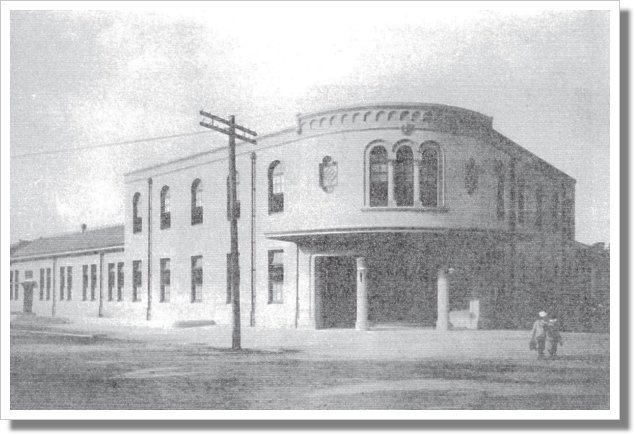

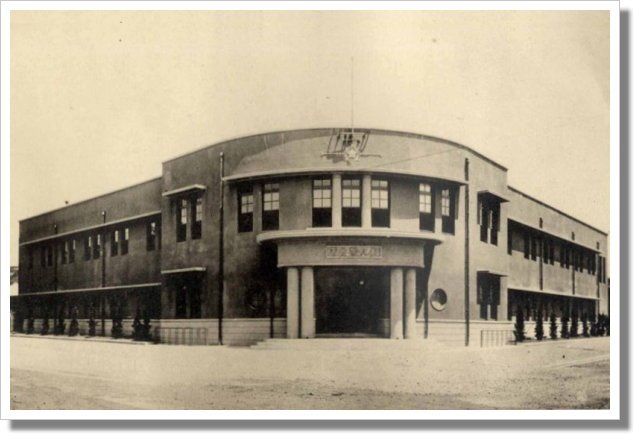

Interestingly, if you take a look at historic photos of both of the buildings (below), you’ll probably notice that they look quite similar in design. This is because they were actually quite generic as the architectural style used to construct these buildings had become common for larger police stations in Japan at the time, which is something I’ll explain in further detail below.

Note: The South Taipei Police Precinct has already been torn down.

Officially opened on April 26th, 1933, the North Taipei Police Station (臺北北警察署 / たいぺいきたけいさつしょ) was constructed a short distance from the original. Replacing a much smaller Qing-era building, which had a bit of a bad reputation (due to protests and arrests of intellectuals in the 1920s), the newer, much larger building was constructed using modern design techniques. Sadly though, it wouldn’t be long until it’s reputation would become exponentially worse than its predecessor.

For the remainder of the Japanese-era, the station remained in operation as normal, but when the Second World War came to an end and the Japanese were forced to surrender control of Taiwan, a number of changes took place, in addition to some pretty terrible events that cemented the station’s place in history. Playing a role in what has become known as the 228-Incident (二二八事件), an island-wide event that started in Daodaocheng, a short distance from the station. It also became home to the Criminal Investigation Corps (臺灣省警務處刑警總隊拘留所), which was later discovered to be part of the state intelligence apparatus that worked hand-in-hand with the infamous Taiwan Garrison Command (警備總部).

Investigations into the history of the White Terror Period (白色恐怖) from 1947 to 1987 are ongoing, so the actual number of political prisoners who passed through the station remains, but what we do know is that the building and the jail within were used extensively to ‘temporarily’ house political prisoners, who were interrogated and tortured in the building, prior to being sent to more ‘private' locations where they were likely to never be seen again.

Considered by the National Human Rights Museum as one of the historical sites of injustice’ (不義遺址) mentioned earlier, the number of political prisoners who passed through the station is unlikely to be an insignificant number, nevertheless, as the political situation in the country started to stabilize by the 1990s, the building became just a regular police station, until it was finally put out service in 2012.

Soon after the ‘Datong Police Station’ (大同分局) moved to a much larger building next door, the original was designated by Taipei City as a Protected Historic Property and plans for restoration were drawn up.

Below, I’m going to provide a brief timeline of the station’s history before I move onto its architectural design:

North Taipei Police Precinct Timeline

1920-1932 (大正9年 - 昭和7年) - The first generation Taipei North Police Station was located within a much smaller building for a twelve year period where the Carrefour hyper-mart exists today. This was the building where Chiang Wei-shui and others were imprisoned.

1932 (昭和7年) - Construction on the new police station starts on August 8th.

1933 (昭和8年) - Construction on the new station is completed on April 15th, and the building is officially opened on April 26th.

1945 (昭和20年) - Soon after the Chinese Nationalists take control of Taiwan, the station is renamed “Taipei #1 Precinct” (第一分局).

1949 (民國38年) - The police station becomes home to the Criminal Investigation Corps, which is officially a ‘police’ organization but is under the umbrella of the state intelligence apparatus, and the building is used for the imprisonment and torture of political prisoners.

1985 (民國74年) - The station is renamed “Ningxia Police Station” (寧夏分局)

1990 (民國79年) - The station is renamed “Datong Police Station” (大同分局)

1998 (民國87年) - The building is officially recognized as a Taipei City Historic Property (市定古蹟)

2006 (民國95年) - Plans are made by the city government to restore the building and convert it into the New Cultural Movement Memorial Hall, once construction on the new Datong Police Branch is completed.

2012 (民國101年) - The Datong Police Station officially moves to its new location (next to the original building) and once the building is vacated, preparations are made for its restoration.

2018 (民國107年) - The Taiwan New Cultural Movement Memorial Hall officially opens on October 14th.

Architectural Design

At this point, you’re probably thinking, is it really necessary to describe the architectural design of a police station? It is after-all just an old building where some terrible things happened. To answer your question yes, I think it’s important to (at least) briefly talk about the design of the building, because there are some tidbits of information that make it quite interesting.

I promise though, I won’t spend as much time as I usually do on this section.

To start, I suppose the first interesting thing about the design of the building is that it part of a very formulaic as far as police stations like this go - If we take a look at the historic police stations constructed during the early years of the Showa-era in both Taiwan and Japan, there are some architectural characteristics that are shared by all of them. So, let’s first take a look at some of historic stations (of a similar size) here in Taiwan so you’ll better understand what I’m talking about.

What you’ll notice in each of the examples above is that they were all similarly constructed on the corner of a road in either a “L” or “V” shape, were generously sized two-leveled structures, and more specifically ranged from 524.6 - 565.2 square meters in total. Essentially, despite a few minor decorative differences, they all more or less followed the same architectural style and size.

After almost forty years of development, by the time the Showa-era came along, the Japanese had become rather adept and had all of the infrastructure in place to construct modern buildings like this in Taiwan. The combination of improved construction techniques, a better understanding of Taiwan’s natural environment, and the availability of construction materials made it much easier for the authorities to construct larger buildings that would be able to withstand the test of time, for a fraction of the price, which made projects like this much more feasible.

If you’ve been reading my articles for any period of time, you’ll probably notice that I tend to focus more on the traditional-looking Japanese-style buildings, most of which were constructed with timber. What’s important to keep in mind with regard to these larger civic buildings, however is that in the aftermath of the devastating Great Kanto Earthquake (関東大地震) in 1923 (大正12), attitudes regarding construction and building safety became an important issue within Japanese society. It was around this time that the use of reinforced concrete structures started appearing more regularly as a more modern approach to construction, safety and the longevity of buildings became paramount. Earthquake-proofing, however became essential within the Governor General’s official building-standard codes after the Shinchiku-Taichu Earthquake (新竹‧台中地震 / しんちく‧たいちゅうじしん) of 1935 (昭和10年) caused massive damage around the island.

Constructed using reinforced concrete with brick load-bearing wall elements and a steel frame, the ‘modern approach’ to architectural design that was taking place here differed from the traditional approach. In the latter, designers placed more importance on the load-bearing ability of the walls to withstand the weight of the roof and the floors above. In this case, the steel frame, brick walls and a network of columns and beams on the ground level and the second floor were better suited to maintain the stability of the building, especially in the case of an earthquake.

One of the most interesting tidbits of information regarding the reinforced concrete that was used to construct this specific building (and several others around the capital) is that the same stone that was made up the original walls that surrounded Qing-era Taipei City. So even though the stone was re-made into the exterior of the building that we see today, the concrete predates the building by more than half a century.

What’s most noticeable with regard to these modern civic buildings is that they were constructed with fewer decorative elements than traditional style buildings. That doesn’t mean they didn’t add any special touches to the building, instead, I’d argue that the what they did add, stands out as somewhat of a lost art-form within modern construction as the Art-Deco architectural style turned what was a simple police station into an elegant building.

Starting from the shape of the building, it may not seem obvious, but the “L-shape” on the corner makes it an opposing structure as it stretches along two different roads. The modern building techniques and steel-frame permitted exterior walls that feature a number of arched and semi-circular windows, which allowed for a considerable amount of natural light to enter the building. The most impressive aspect of the exterior is where the building curves in a ‘half-moon’ shape on the corner, which is where you’ll find the covered portico that feature columns and a set of stairs that open up to the front door.

Once inside, you get to see more of the Art-Deco decorative elements at work with the spacious front hall, high ceilings, large arched corridors and the absolutely beautiful staircase located in the center of the building. Suffice to say, over the past nine decades, a considerable amount of alterations have taken place within the interior of the building, so the number of rooms within the space is somewhat unclear, but what remains true is that after the war, the station was home to more than two-hundred officers, making it a pretty cramped space. This ultimately necessitated a third floor expansion in the 1960s, which has since been removed to restore the building to its original likeness.

One of the main attractions for most visitors today is the jail area (拘留所) of the building, which is connected to the rear of the building. The fan-shaped jail allowed for a single officer to watch over seven triangular jail cells from a station in the middle. For most visitors, it’s likely their first time to encounter such a space, but it’s important to remember the nefarious events that took place in Taiwan over the past century, making this a solemn place for the people who suffered political persecution within the building and elsewhere. Much of the jail has been restored to its original condition and visitors are free to enter one or two of the cells to experience the cramped space.

Directly to the rear of where the presiding officer would have watched the prisoners is a room that is home to the infamous Water Dungeon (水牢), a torture device that was constructed during the Japanese-era, but widely used later on as a means of extracting confessions out of political prisoners. A live-feed has been installed to allow visitors to view what it looks like within the dungeon, but you can’t actually go down, nor would you probably want to.

On that note, I’m going to move on to why this historic building has become home to a memorial hall for the political prisoners who had the misfortune of being brought to the building both during the Japanese era and the current era.

Taiwan New Cultural Movement Memorial Hall

(臺灣新文化運動紀念館)

Now that I’ve introduced the history and architectural design of the building itself, I think it’s important to first expand on the history of the “New Cultural Movement” (新文化運動) before I introduce the memorial hall that occupies the building today, so that readers have a better understanding as to why it’s a significant memorial for the people of Taiwan, and especially with regard to the neighborhood where it’s located.

Having written about the history of the Dadaocheng area several times already, I’m going to start simply by explaining briefly some of the important events that led up to the formation of the New Culture Movement: Originally the Bangka (艋舺) area, known today as “Wanhua District” (萬華區) was the first part of the capital that was opened up for international exchange and trading with a port that allowed boats to travel up the Keelung river and out to sea. The economic prosperity of the area however brought about issues between groups of immigrants that hailed from different regions of China’s Fujian Province (福建省).

Most importantly with regard to the Dadaocheng area, the immigrants who came to Taiwan from Tong-An County (同安縣), which is today a northern district of Xiamen city (廈門市) were the ones who had the most trouble as the more dominant groups weren’t willing to share their economic prosperity with them.

In 1853, hostilities broke out (頂下郊拚) between the four major groups of immigrants who occupied the port area, and ultimately finding themselves on the losing side of the conflict, the immigrants hailing from Tong-An county packed up and moved out of Bangka, resettling in nearby Dadaocheng.

Settlement in the Dadaocheng area (pronounced: Tōa-tiū-tiâ in Taiwanese Hokkien) starting a few years prior by another group of immigrants from Tong-An, who had migrated from Taiwan's northern port of Keelung to do business in the city, so those who found themselves fleeing Bangka were welcomed. It was a move that ultimately proved to be extremely beneficial for those displaced as they used their resources and knowledge to further develop Dadaocheng, which also had its own wharf.

Looking back, losing the feud was probably the best thing that could have happened given that the port in Bangka shortly after started having silting issues, making the it unusable for the boats that would have docked there, allowing Dadaocheng to transform itself into a commercially successful port of trade. By the time the Japanese took control of Taiwan in 1895, the Dadaocheng area was the most commercially successful area of the island with international exchange and trade fueling economic prosperity, and more importantly for today’s topic, attracting literati and scholars from all over Taiwan.

By the 1920s, intellectuals in Taiwan, influenced by social movements taking place elsewhere around the world, started forming groups advocating for an end to colonial rule and for national self-determination. Scholars such as Chiang Wei-shui (蔣渭水) and Lin Hsien-tang (林獻堂) founded groups like the Taiwan Cultural Association (台灣文化協會), and the Taiwanese People’s Party (臺灣民眾黨), one of which is the inspiration for the memorial hall today.

Links: Chiang Wei-shui | Lin Hsien-tang (Wiki)

The New Culture Movement advocated for ‘a self-help enlightenment movement for the social liberation and cultural advancement of the Taiwanese people’ inspired by President Woodrow Wilson’s promotion of the ideology of national self-determination. Even though many of the intellectuals in the group were among the few lucky enough to be highly educated in Japanese universities, they still advocated that the ‘cure’ for Taiwan’s sociocultural and national illnesses were simple things such as access to formal education, professional training, kindergartens, libraries and newspaper reading clubs.

To assist in solving these problems, the association published the Taiwan People’s Daily (台灣民報), a newspaper that served as an alternative to the colonial government’s official newspaper, and they organized ‘cultural schools’ for the less fortunate in society, held cultural lecture groups and seminars, established ‘newspaper reading clubs’ (a topic that is wonderfully put on display at the museum today), organized and performed cultural plays and showings of foreign films, and opened book stores around the island.

All in the hope of cultivating the seeds of literacy and social enlightenment among the people of Taiwan.

To say the least, in many ways, the New Cultural Movement’s goals started creating change throughout Taiwan, and many of their ideologies continue to be promoted today on the road to strengthening the nation’s democracy and civil society.

However, even though it all might sound utopian, the reality is that the Japanese empire at the time was quickly turning into a fascist state, and these social movements seeking to promote Taiwanese self-determination weren’t exactly looked upon favorably by nationalists. Thus, the government cracked down on these groups and members were arrested and imprisoned. Commemorating those efforts, the New Culture Movement Memorial Hall (臺灣新文化運動紀念館) was established within the very same police station where Chiang Wei-shui, and many of his contemporaries were held after their arrests.

Established on October 14th, 2018 (民國107年), the historic police station has been completely restored and features educational exhibits about the New Culture Movement on the first floor and a number of revolving exhibitions on the second floor that focus on the various aspects of the movement and it’s effect on Taiwanese society from the 1920s until now.

In addition to the permanent and revolving exhibitions within the memorial hall, the staff is tasked with organizing seminars, forums, book exhibitions, guided street tours, bazaars and concerts throughout the year, making a visit to the hall one that tourists and every day citizens alike can enjoy on more than one occasion.

And hey, if you’re in the area and are simply looking for a relaxing place to sit and enjoy a coffee, you can visit the 8jincafé (八斤所) on the first floor, to the left of the main entrance, where you’ll get to enjoy the historic ambiance of the old building while enjoying some freshly brewed single-origin coffee.

Link: 8jincafé (八斤所)

As one of the (current) thirty-one sites under the stewardship of the National Human Rights Museum’s (國家人權博物館) ‘Historical Sites of Injustice’ (不義遺址) project, the memorial hall located within the historic police station today focuses on the Cultural Movements of the Japanese-era, but it goes without saying that the police station was also involved in what the Human Rights Museum defines as a “detention, interrogation, torture, coercion, prosecution, trials, and internment of political dissidents during the White Terror period’ which “can be found all over Taiwan, including on the islands of Kinmen, Matsu and Penghu” and “were witnesses to the major historical traumas undergone by Taiwan in its development of human rights.”

As the police station became home to the Criminal Investigation Corps (臺灣省警務處刑警總隊拘留所), which unofficially acted as part of the state intelligence apparatus with police serving a dual-role as members of the infamous Taiwan Provincial Security Command (省保安司令部) and the Taiwan Garrison Command (警備總部) who used the building as a temporary detention center for confining political prisoners during the White Terror period where they would be questioned and tortured prior to being sent elsewhere.

The topic of transitional justice is a heavy one, especially as the historic crimes of the White Terror Period (白色恐怖) continue to come to light, but I do recommend anyone reading this to take some time to check out the Sites of Injustice website linked below, which provides excellent resources in both Chinese and English regarding one of the longest periods of imposed Martial Law in the world’s history, where the people of Taiwan were subjected to political repression and unspeakable cruelty. The website provides information on what has been uncovered as well as the sites that we’re able to visit to learn more about the topic.

Link: Historical Sites of Injustice (不義遺址)

The Taiwan New Cultural Movement Memorial Hall is open from Tuesday to Sunday (Closed on Mondays) from 9:30 - 17:00 and visiting is free of charge.

Website: Taiwan New Cultural Movement Memorial Hall | Facebook (Both Chinese Only)

Getting There

Address: #87 Ningxia Road, Datong District, Taipei (大同區寧夏路87號)

GPS: 25.059430, 121.514900

Located in Taipei’s historic Datong District (大同區), the Taiwan New Cultural Movement Memorial Hall is conveniently positioned within walking distance from several of the city’s MRT stations, and is likewise serviced by numerous bus routes, making getting to the area relatively easy for most traveller.

Within walking distance from Ningxia Nightmarket (寧夏夜市) and the Dadaocheng (大稻埕) area, there are considerable amount of things to see and do while visiting the area, and the addition of this new memorial hall is an excellent stop for anyone hoping to learn more about Taiwan’s modern history.

Taipei MRT

One of the easiest ways to visit the Memorial Hall is to make your way to any of the three subway stations listed below and from there walking to the hall. From either of the three stations, it shouldn’t take any longer than ten minutes to reach the hall.

Shuanglian MRT Station (雙連捷運站) - From Exit 1, turn left on Minsheng West Road (民生西路) and continue walking straight until you reach Ningxia Road (寧夏路) where you’ll turn right and continue walking straight until you reach the hall.

Minquan West Road MRT Station (民權西路捷運站) - From Exit 3 walk south until you reach Jinxi Street (錦西街) where you turn right and walk straight until you reach the hall.

Daqiaotou MRT Station (大橋頭捷運站) - From the station simply walk south down Chongqing North Road (重慶北路) until you reach the Carrefour. The memorial hall is located to the rear of the building.

Bus

Located between the Minsheng Chongqing Road Intersection (民生重慶路口站) and the Liangzhou Chongqing Road Intersection (涼州重慶路口站) bus stops, travelers have a number of options for bus routes to the area. Both of the bus stops are located along the bus Chongqing North Road (重慶北路), and once you get off, you’ll have to cross to the side of the street where you see the Chongqing Road Carrefour (家樂福重慶店). From there, the memorial hall is a short distance to the rear of the building, which means that taking the bus is one of your best options.

The following buses are serviced by both of the stops: #2, #63, #215, #223, #250, #288, #300, #302, #304, #306, #639, #757, #966,

Click on any of the links above for the route map and real-time information for each of the buses. If you haven’t already, I recommend using the Taipei eBus website or downloading the “台北等公車” app to your phone.

Youbike

There are also a number of Youbike Docking Stations surrounding the area where the Memorial Hall is located. The closest of which can be found within the Chiang Wei-Shui Memorial Park (蔣渭水紀念公園), next to the current police station. If you’re making your way around town on one of the publicly available Youbike’s, you’ll be able to dock your bike nearby, or find another one once you’ve finished checking out the memorial hall.

If you haven’t already, I highly recommend downloading the Youbike App to your phone so that you’ll have a better idea of the location where you’ll be able to find the closest docking station.

Links: Youbike 1.0 - Apple | Android | Youbike 2.0 - Apple | Android

History in Taiwan can be a complicated subject at times, and even though this building’s history spans both the Japanese Colonial era and the subsequent Martial Law period, the architectural beauty of the historic building is foreshadowed by the terrible things that took place within. Now that the country is on the path to addressing transitional justice, the re-opening of this particular space as a memorial for those who suffered within is certainly a helpful way to educate people about Taiwan’s struggle to attain the democracy that it enjoys today.

References

Taipei New Cultural Movement Memorial Hall (臺灣新文化運動紀念館)

走訪台灣新文化運動紀念館,回顧台灣文化協會的百年奔放與啟蒙 (The News Lens)

臺灣新文化運動紀念館》茶金拍攝景點,水牢及互動體驗讓歷史變有趣 (可大王愛旅行)

臺灣省警務處刑警總隊拘留所 (不義遺址資料庫)

臺灣新文化運動紀念館 關不住的文化覺醒 (台北旅遊網)

臺北北警察署 (Wiki)

原臺北北警察署 (國家文化資產網)

原臺北北警察署 (文化部)

台北-大同 臺北北警察署 (Just a Balcony)