When I first started writing on this website, I spent quite a bit of time focusing on Taiwan’s historic places of worship, or at least, some of the more popular and well-known temples in the country. Why? Well, its pretty simple, its what I was interested in, and it goes without saying that temples here are absolutely beautiful.

Later, when I branched out and started publishing articles about other kinds of tourist destinations and attractions around Taiwan, I made sure to maintain a focus on the subjects that I enjoy, which for the most part have to do with the local religion, mountains and nature, and urban exploration. It takes quite a bit of my personal time to write these articles, so its important that I write about the things I care about. Thus, one of the common themes that you may have noticed by now is that the places I write about almost always share a relationship with the history of Taiwan, and are destinations that have an interesting story to tell. Afterwards, when I started writing about destinations related to the fifty year period of colonial rule, known as the Japanese-era, my research forced me to spend a considerable amount of time learning more about the architectural design characteristics of those historic places I was writing about, so that I could better explain their significance.

On a personal note, something I’ve probably never mentioned is that both my father and my late grandfather are (were) highly-skilled and widely-sought master carpenters back home. After my parents divorced, I’d sometimes get taken to a work site where they were in the middle of constructing some beautiful new house (likely in the hope that I’d carry on the family tradition), and although our relationship was never really that strong, I had to respect the mathematical genius it took for them to construct some of the things they were were building. Looking back, I probably never expected that years later, I’d be spending so much time researching and writing about these things, but in order to better understand the complicated and genius designs of those historic places I was writing about, I had to put in the extra effort to learn about their design characteristics.

Getting to the point, recently, while writing an article about Taipei’s Jiantan Historic Temple (劍潭古寺), I figured I’d do what I normally do and spend some time writing about the its special architectural characteristics. Sadly, writing that article forced me to face the sad truth that after all these years learning about the intricacies of traditional Japanese architectural design, that I actually knew very little about traditional ‘Taiwanese’ design. Finishing that article ended up taking considerably longer than I originally expected because I spent so much time researching and learning about the various elements of local architectural design, and the terms, many of which were completely new to me, that would be necessary to properly describe the design of the temple.

Suffice to say, much of what I ended up learning during those days spent in coffee shops researching the topic were things that I could go back and apply to dozens of articles that I’ve published in the past, but going back and adding descriptions of the architectural design of all of those places feels like a daunting task at the moment - so, for the time being, I’ve decided to make use of a collection of photos that I’ve taken over the years to offer readers a general idea about the intricacies of one of Taiwan’s most common styles of architectural design, and more specifically the decorative elements that make these buildings so visually spectacular.

While this might sound corny, when it comes to traditional Taiwanese architectural design, the old adage, “a picture is worth a thousand words” is something that I think can be expanded upon as “a Taiwanese temple is worth a thousand stories,” each of which you’ll find is depicted in great detail in every corner of a temple. Unfortunately, for most people, locals included, these stories remain somewhat of a mystery, and for visitors to Taiwan, this is a topic that hasn’t been covered very well in the English-language.

Obviously, the intent here is to help people better understand what they’re seeing when they’re standing in front of one of these buildings, however even though this article will be a long one, it’s important to keep in mind that I’m only touching upon the tip of the iceberg of this topic, which is something that is deserving of years of research.

‘Hokkien’ or ‘Taiwanese’?

To start, I should probably first address the wordage I’m using here, which should help readers understand some of the complicated cultural and historic factors involved. People often find themselves in heated arguments online when it comes to this topic, and although that’s something I’d prefer to avoid, as is the case with almost everything in Taiwan these days, there are some political factors involved. Whether or not you agree, when I use the term “Taiwanese-Hokkien,” I’m doing my best to use an inclusive term that reflects the history of Taiwan, and the current climate we find ourselves in with regard to the complicated relationship that Taiwan shares with its neighbor to the west.

Over the years, one of the things I’ve noticed that causes the most amount of confusion, and debate, is with regard to the difference between ‘nationality’ and ‘ethnicity.’ This is something that I’ve always found particularly confusing, mostly due to my own personal background; So, if you’ll allow me, let me make an analogy, I’ll try to explain things that way.

If you weren’t already aware, I grew up in the eastern Canadian province of Nova Scotia, an area that has been colonized by both the French and English. However, for much of its modern history, Nova Scotia, which is Latin for ‘New Scotland,’ was predominately populated by immigrants hailing from Scotland.

Being of Scottish ancestry myself, people at home would probably think I had mental issues if I suddenly started claiming that the province was part of Scotland’s sovereign territory, simply because of the history of immigration.

Similarly, in Nova Scotia, we speak a dialect of French, known as ‘Francais Acadien’ which, unlike the language spoken in Quebec or France, is a variation that hasn’t really changed much over the past few hundred years.

Thus, if I were to contrast the history of my homeland with that of Taiwan’s history, Chinese immigration to Taiwan is an example of how colonization in the early seventeenth century brought about a divergence, and a split, when it comes to language and culture.

The earliest Chinese migrants to the island hailed from what is now China’s Fujian Province (福建省), more specifically Chaozhou (潮州), Zhangzhou (漳州) and Amoy (廈門), and like the Scots who fled to Canada, many of those who came to Taiwan did so to escape economic hardship and persecution at home. This mass movement of people, the vast majority of whom were of ‘Southern-Fukienese’, or ‘Hokkien’ (閩南) in origin, sent most people on their way to more hospitable locations, such as Singapore, Malaysia, the Philippines, Indonesia, Myanmar, Southern Thailand, Cambodia and Vietnam, and is why you’ll still find considerably large ethnic Chinese populations in those countries today.

Similarly, Taiwan just so happened to be another one of the destinations where the immigrants came by the boatloads, but unlike the other areas mentioned above, the island wasn’t exactly what would be considered the ‘choice’ destination for most of the migrants due to the lack of development and the harsh conditions on the island.

Coincidentally, this is a topic that I covered quite extensively after a trip to Vietnam with regard to the Assembly Halls (會館) that were constructed in the historic trading port of Hoi An (會安), where groups of migrants pooled their resources together to create places to celebrate their language and cultural heritage.

With regard to those Assembly Halls, what is interesting is that the Hokkien were just ‘one’ of the ethnic groups hailing from that particular region of China that ended up migrating south, starting mostly during the Ming and Qing Dynasties. In fact, even though the term “Hokkien” refers to the people from “Southern Min”, they are part of a large number of ethnic groups, whose ancestry originated in the Central Plains of China several thousand years ago. However, similar to Taiwan’s other major ethnic group of migrants, the Hakka (客家), the Hokkien people are renowned for being well-traveled, and within ethnic-Chinese communities around the world, you’ll be sure to find a large portion of Hokkien people who have brought with them their own own particular style of architectural design, folk arts, cuisine, religious practices, and folklore, they have also adapted influences of their new homelands.

In Taiwan’s case, over the past few centuries, Hokkien language and culture has been influenced by their interactions with the Hakka, Indigenous Taiwanese, Europeans, and the Japanese. Such is the case that linguistically-speaking, the language spoken in Taiwan makes it difficult (not impossible) for speakers of the language hailing from China or South East Asia to comprehend, which have also had linguistic divergences of their own. Sadly, though, the Hokkien language has had a complicated history in Taiwan given that it was suppressed by both the Japanese and Chinese Nationalist colonial regimes.

Yet, despite the language going through a period of decline in the number of speakers over the past century, it has gone through somewhat of a revival in the decades since the end of Martial Law (戒嚴時期), thanks to the ‘mother-tongue movement’, which seeks to revive, restore and celebrate Hokkien, Hakka and Taiwan’s indigenous languages.

Nevertheless, as I mentioned earlier, an area of contention with regard to the language has to do with its official name, which tends to be quite political, and how it is named really depends on who you’re talking to. As is the case with Mandarin, which is referred to in Mandarin as the “National Language” (國語), “Chinese” (中文), or the “Han Language” (漢語), Hokkien is often also referred to as “Taiwanese” or “Tâi-gí” (台語). People who refer to the language as Hokkien often do so because they feel the name ‘Taiwanese’ belittles the other languages spoken on the island while the opposing side considers the term “Hokkien” inadequate because it refers to a variation of the language spoken in China, and not a language that is part of the beating heart of Taiwan’s modern identity. I’m not here to tell you what name you should use to refer to the language. That’s entirely up to you, and no matter what term you prefer, you’re not likely to end up insulting anyone.

Obviously, many things have changed since the seventeenth century, and both China and Taiwan have developed separately, and in their own ways. Shifting away from the divergence of the language, one of the other more noticeable areas where the two countries share some similarities, yet also diverge at the same time (at least from the perspective here in Taiwan) is with regard to the way Hokkien architectural design, and its adherence to cultural folklore is both created and celebrated.

One claim you’ll often hear on this side of the Taiwan strait is that Communism, and more specifically, the Cultural Revolution (文化大革命) resulted in an irreparable amount of damage to traditional Chinese cultural values and traditions, whereas in Taiwan, you’ll discover that traditional culture is widely celebrated. Personally, having lived in both countries, I’d argue that this is a massive over-simplification of the issue, and not necessarily always the case, but it is true, especially in the case of religious practices, that many of the traditional cultural values that are widely practiced and accepted here in Taiwan have not fared as well in China over the past century.

If you’ve spent any time in Taiwan, it should be rather obvious that traditional culture is widely celebrated here, and most would agree that the nation is home to some of the most important examples of Hokkien architectural design and folklore that you’ll find anywhere in the world. This isn’t to say that you won’t find a considerable amount of traditional architectural design in China, or in immigrant communities in South East Asia, but no where will you find such a large concentration as in Taiwan.

Even though Taiwan has its own fair share of folklore and heroic figures, one aspect of Hokkien culture that you’ll find celebrated here is with regard to its cultural history, especially with events that took place in China hundreds, if not thousands of years ago. The historic events and legends that you’ll find displayed on the walls and roofs of these buildings across Taiwan are quite adept at putting that relationship on display. This is the case not only with the architectural and decorative elements of Taiwan’s temples, but also with regard to the local folk religion figures who are worshiped inside, many of whom are historic Hokkien figures who have been deified for their heroic actions, but for the large part, have never stepped foot in Taiwan.

So, even though the topic might be uncomfortable for some, it doesn’t change the fact that Taiwan’s rich cultural history has been guided in part by immigrants from China, who brought with them their cultural values. That being said, even though the two sides of the strait share links with regard to culture, language and ethnicity, that doesn’t mean that they inextricably linked with one another, or that one side has the right to claim sovereignty over the other.

Link: As Taiwan’s Identity Shifts, Can the Taiwanese Language Return to Prominence? (Ketagalan Media)

Whether you refer to the language as ‘Taiwanese’ or ‘Hokkien,’ it is estimated to be spoken (to some degree) by at least 81.9% of the Taiwanese population today, and while it was once more commonly associated with older generation, and informal settings, Taiwanese has become part of a newly formed national identity. In recent years, the youth of the country have embraced the language as a means of differentiating themselves not only from the neighbors across the strait, but the Chinese Nationalist Party (國民黨), which ruled over Taiwan with an iron fist for half a century prior to democratization. Sorry Youth (拍謝少年), EggplantEgg (茄子蛋) and AmazingBand (美秀劇團) are just a few examples of some of the musical groups that perform primarily in Taiwanese, and television production has gone from low-budget soap operas for the older generation to contemporary large-budget Netflix-level productions that have become pop-culture hits.

Link: Beyond Pop-Culture: Towards Integrating Taiwanese into Daily Life (Taiwan Gazette)

The resurgence of Taiwanese since the end of Martial Law, however, is just one area where traditional ‘Hokkien’ culture has experienced a revival. One of the more admirable things about Taiwan, and is something that is (arguably) missing in China, is the amount of civil activism that takes place here. In China, for example, if the government proposes urban renewal plans that will ultimately destroy heritage structures, and displace people from their homes, there isn’t all that much in terms of opposition (this has been changing in recent years), but here in Taiwan, people have little patience for this sort of behavior, and are very vocal and willing to take to the streets to vigorously fight for the preservation of the nation’s heritage structures. Some might argue that this level of civic participation slows development, but when a government at any level is held to account, it is a good thing isn’t it?

Given that most the oldest heritage buildings that you’re likely to find in Taiwan today, are of Hokkien origin, what you’ll experience at some of the historic buildings that have become popular tourist attractions is a showcase in the masterful beauty of this style of architectural design. The Lin An Tai Mansion (林安泰古厝) in Taipei and the Lin Family Mansion (板橋林家花園) in Taoyuan are just two examples of historic mansions that have been restored and opened to the public in recent years. Similarly, places of worship, where this style of design shines at its brightest, such as Taipei’s Longshan Temple (艋舺龍山寺) and Bao-An Temple (大龍峒保安宮) are highly regarded as two of the most important specimens of Hokkien-style architecture anywhere in the world.

While the examples above are just a few of the more well-known destinations for tourists here in the north, its also true that no matter where you’re traveling in the country, you won’t find yourself too far from an example of this well-preserved style of architectural beauty. So, now that I’ve got that long-winded disclaimer out of the way, let’s start talking about what makes Taiwan’s Hokkien-style architecture so prolific.

Taiwanese Hokkien-Style Architecture (臺灣閩南建築)

Before I start, it’s probably important to note that Hokkien-style architecture in Taiwan shares similar elements of design with many of the other traditional styles of Southern Chinese architectural design. You may find yourself asking what makes this particular style of design so special and you’d probably also expect a long and complex answer, but that’s not actually the case. What stands out with regard to this architectural style is that (almost) every building is a celebration of their culture, history and folklore - and the means by which these celebrations are depicted is through a decorative style of art that is most common among the Hokkien people.

While its true that the Hokkien people who migrated to Taiwan originated in Southern China, and it’s also true that you’ll find some of these design elements adorning traditional buildings there as well, as I mentioned earlier, during the period that the two have been split, alterations to the style and the method for which these things are constructed have changed. Today, Taiwan is home to a much greater volume of buildings making use of this architectural design, and the Hokkien craftspeople here have perfected their art as they have adapted to their new environs, with modern construction techniques streamlining the process.

In this section, I’m not going to focus on specific construction techniques or the materials used to construct buildings. Instead, I’m going to focus on two elements that define Hokkien style architecture: The Swallowtail Roof (燕尾脊), and the cut-porcelain mosaic (剪瓷雕) decorative designs, both of which are the means by which the Hokkien people so eloquently tell their stories.

The Swallowtail Ridge (燕尾脊)

If you’ve been following my blog for any period of time, you’re probably well-aware that I spend quite a bit of time describing the architectural design of the roofs of the places I visit. For locals, these things are probably just normal aspects of life, so I doubt they put much effort into thinking about the mastery of their architectural design, but for me (and possibly you if you’re reading this), a foreigner, whenever I see these impressive roofs, whether they’re covering a Hokkien or Hakka building, or a Japanese-era structure, I’m always in awe of the work that goes into constructing them.

For most of us westerners, a roof is just a roof, it doesn’t really do all that much other than cover your house, and protect you from the elements. Here in Taiwan, though, when buildings are constructed, a lot of thought and consideration goes into the design, especially when it comes to the decorative elements that are added. So, even though the Hokkien-style Swallowtail Ridge roof has become one of the more common styles of traditional architectural design that you’ll find here in Taiwan, they’re still quite amazing to behold.

The ‘swallow’ (燕子) is a pretty common species of bird here in Taiwan, so common in fact that as I’m sitting in a coffee shop writing this article, there are about twenty of them relaxing on a power line just outside the window. Even though swallows are considered to be quite beautiful, I’d (probably unfairly) compare them to crows back home in Canada. The biggest difference between the two, though, is that crows in Canada are considered pests, and if they construct a nest near your home, you do your best to get rid of it. In Taiwan on the other hand, if a pair of swallows construct a nest near your home it is considered to be good luck and people will often make an effort to ensure that the nest is safe, and that that babies won’t fall to their deaths.

With that in mind, it is common in Taiwan for people to say that ‘swallows always return to their nest,’ a metaphor for the feeling of ‘homesickness’ people have while living far away. Given that the Hokkien people are a well-traveled bunch, the swallow, and more specifically, the swallowtail roof is a reminder of home, childhood memories, and is one of the reasons why this is a style of design that never gets old, as it is so culturally entrenched in the hearts of the people here.

So what exactly is a Swallowtail Roof? Well, that answer is something that I personally found surprising.

Speaking to the different styles of roof mentioned earlier, before I give you the answer to the question above, it’s probably a good idea to provide some ideas of the common styles of architectural design that are common in Taiwan. I’ve seen estimations that there are at least sixty different variations of roof design common within Southern-Fujianese architecture, but those variations can be easily divided up into six specific styles of design, many of which can be found all over Taiwan today.

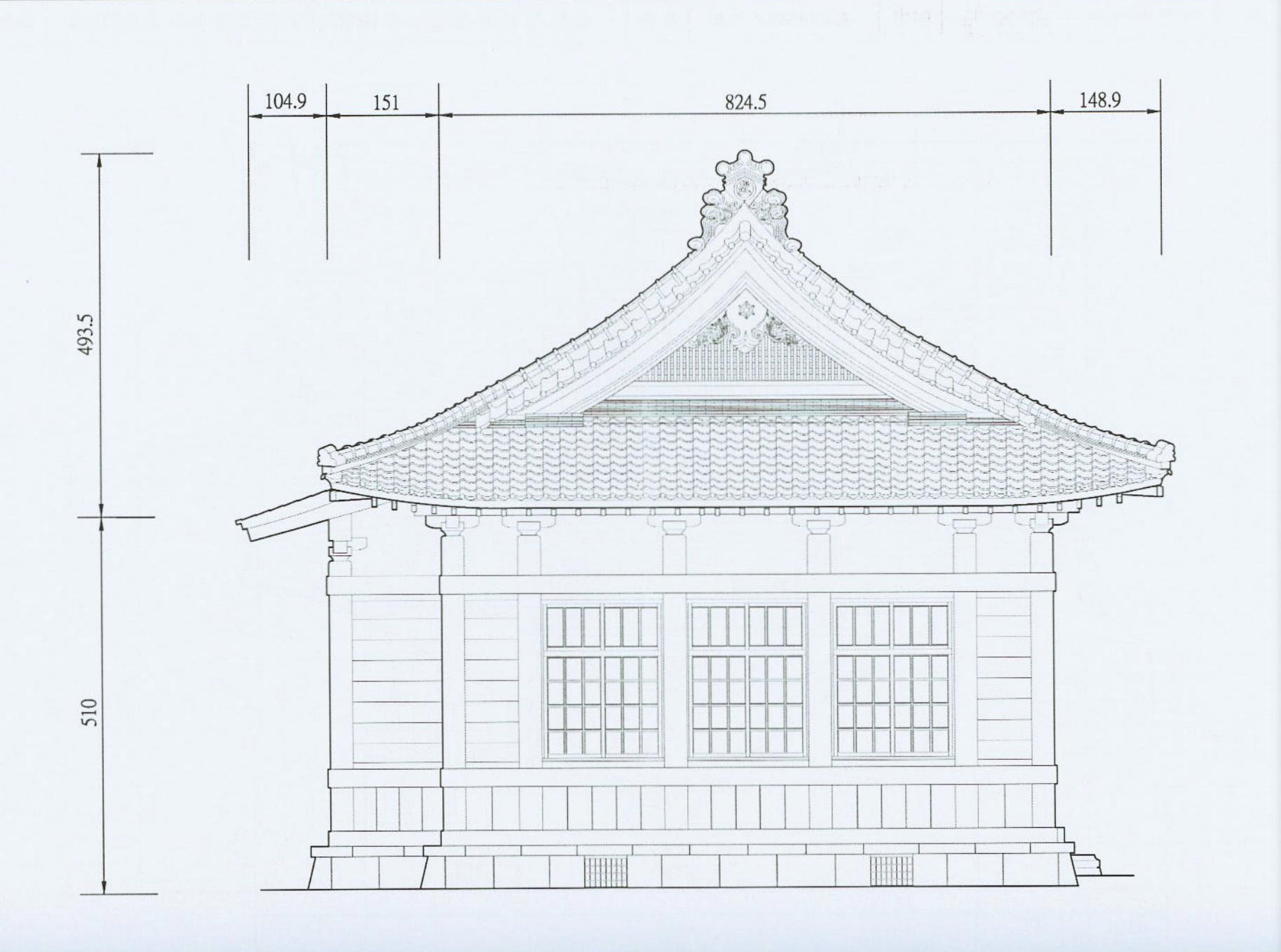

Hip Roof Style (廡殿頂) - a style of roof with four slopes on the front, rear, left and right. It is the highest ranking of all of the styles of architectural design and is reserved only for palaces and places of worship. The National Theater and Concert Hall (國家兩廳院) at Chiang Kai-Shek Memorial Hall are pretty good examples of this style of design.

Hip-and-Gable Style (歇山頂) - One of the most common styles of roof design, the hip-and-gable roof is a three-dimensional combination of a two-sided hip and four-sided gable roof. Many of Taiwan’s places of worship, ancestral shrines, and historic mansions use this style. It is a style of architectural design that is thought to have originated during the Tang Dynasty (唐朝), and is used all over East Asia, most significantly in Japan.

Pyramid-Roof Style (攢尖頂) - a style of roof that is more common for ‘auxiliary buildings’ rather than temples. You’ll often find this style of roof covering pavilions in parks, drum towers at temples, etc. Within this specific style, it is uncommon to encounter swallowtail designs, although they might be adorned with some of the porcelain art that I’ll introduce below.

Hard Mountain Style (硬山頂) - a basic style of roof design that features two slopes on the front and rear of the building. This style of design is most common in Hokkien houses and mansions around Taiwan. Despite being more subdued compared to the other styles of roof, it is a functional and practical roof that is easily repaired.

Overhanging Gable Style (懸山頂) - a style of roof that became common in Taiwan during the half century of Japanese Colonial rule. This type of roof is a variation of the hip-and-gable roof mentioned above and features steep sloping hips in the front and rear of the building with triangular ends on both sides of the building.

Rolling Shed Roof (捲棚頂) - considered to be similar to both the Hard Mountain and Overhanging Gable styles above, this specific style of roof is common in historic homes in Taiwan, but doesn’t feature a vertical ridge on top.

Of the six styles of roof listed above, it has been most common for the Hokkien people to make use of the ‘Hip-and-Gable’, ‘Hard Mountain’, and more recently, the ‘Overhanging Gable’ styles of architectural designs for their homes and places of worship. Notably, these particular styles of design were the three that are most easily adapted to Hokkien decorative elements, and the natural environment of Southern Fujian and Taiwan. It’s important to remember that in both of these coastal areas, any building that was constructed would have to be able to respond to the area’s natural environment and thus, sloping roofs like these helped to ensure that they were protected from periods of torrential rain.

Ultimately, the alterations that the Hokkien people made were to better fit their needs in ways that were both functional and decorative at the same time. To answer the question above, though, one thing that doesn’t often get mentioned in literature about Hokkien ‘Swallowtail Roofs’ is that they’re not actually a specific style of architectural roof design. In fact, the so-called ‘swallowtail’ is just a decorative modification of a traditional style of roof. The ‘swallowtail’ as we know it today, though, comes with several additions and decorative elements to a roof’s design that helps to ensure its cultural authenticity.

Obviously, the most important aspect is the curved ‘swallowtail ridge’ (燕尾脊 / tshio-tsit) located at the top of the roof of a building. With both ends of the ridge curving upwards, it is a design that is likened to the shape of a sharp crescent moon, and the straight lines on the ridge add beautiful symmetry to a structure. The Mid-Section (頂脊 / 正脊) of the curved ridge tends to be flat, and is an important section of the swallowtail where decorative elements are placed that assist in identifying the purpose of the building. The curved ridge also features a flat section facing outward, known as the ‘Ridge Spine’ (西施脊), where you’ll often find an incredible amount of decorative elements in the form of Hokkien cut porcelain carvings (剪瓷雕). Connecting to the ridge spine, you’ll also find Vertical Ridges (規帶) running down both the eastern and western sides of the sloping roof. These ridges are functional in that they help to keep the roof tiles locked in place, but they’re also decorative in that they feature platforms (牌頭) on the ends where you’ll find even more elaborate decorative additions.

Finally, one of the more indicative elements of Hokkien style roofs are the red tiles that cover the roof. As mentioned earlier, it is important for these roofs to be able to take care of rain water, so you’ll notice that these roofs feature what appear to be curved lines of tiles that look like tubes running down the roof. Between the tube-like tiles (筒瓦), there are also flat tiles (板瓦), which are meant to allow rainwater to flow smoothly down the roof. Crafted in kilns with Taiwanese red clay, the tiles might not seem all that important, but they do offer the opportunity to add more decorative elements in that the tube-like tiles have circular ends (瓦當) where you’ll find a myriad of designs depending on the building.

Suffice to say, when it comes to the addition of a swallowtail ridge to a building’s roof, there are a number of considerations that factor into their construction. The length, degree of curvature and decorative elements are all aspects of the design that are carefully planned, but are mostly determined by the size of a building, and more importantly the amount of money that is willing to be spent.

You’ll probably notice that the grander the swallowtail, or the number of layers to a building’s roof, is usually a pretty good indication of how important a place of worship is, or the deities who are enshrined within. In Taipei, Longshan Temple (艋舺龍山寺) is probably one of the best examples of the grandeur of a historic temple of importance, while the recently reconstructed Linkou Guanyin Temple (林口竹林山觀音寺) is probably one of the best examples of the spectacular things one can do with this style of design if you have deep enough pockets to throw at it.

Cut porcelain carvings (剪瓷雕)

Hokkien-style ‘Cut Porcelain Carvings’ come in several variations, each of which represent different themes or types of objects that are considered culturally or historically significant to the community, and the local environment. The art of cut porcelain carvings is thought to have been brought to Taiwan by Hokkien immigrants at some point in the seventeenth century, and while there are arguments as to whether Taiwan’s porcelain art originated in Chaozhou (潮州), Quanzhou (泉州) or Zhangzhou (漳州), it’s important to note that the craftsmen in Taiwan today have made a number of alterations to the traditional style which makes it difficult to determine the origin.

So, let’s just call it Taiwanese, then?

Another reason why its difficult to know how the decorative art arrived in Taiwan is due to the fact that authorities during the Qing Dynasty placed a ban on migration across the strait, which means that it was likely brought by undocumented migrants who fled the political situation in China, possibly during the late stages of the Ming Dynasty (明朝) when Koxinga (鄭成功) and his pirate navy arrived on the island given that they set off from the port in Amoy, which is today Xiamen City (廈門市) in Fujian.

One would think that this traditional style of art might be suffering from a lack of craftsmen in the modern era, few homes today are constructed in the traditional Hokkien style of architectural design, but you’d probably be surprised to learn that the creation of this cut porcelain art remains a thriving business in Taiwan, with newly constructed temples requiring new designs in addition to the thousands of already well-established places of worship across the country requiring some restoration work. Suffice to say, the creation of these carvings takes a considerable amount of time and craftsmanship, which also means that they’re quite expensive. Thus, you’ll find several large and well-known workshops owned by craftsmen, who have been working in the field for generations, but you’ll also find people who have branched out on their own and started creating their own work.

‘Cut porcelain carvings’, which are likened to life-like mosaics, are essentially a collage of small pieces of porcelain fixed to a pre-formed plaster shape, craftsmen recycle material from bowls, plates and pots, which they then crush into smaller pieces, dye with bright colors, and then attach to an object, which could be human-like figures, animals, flowers, etc. Decorative in nature, the carvings are also considered to represent themes such as ‘good luck’, ‘good fortune’, ‘longevity’, ‘protection’, etc.

As mentioned earlier, one of the major differences between the traditional Hokkien art and what’s practiced today is that artisans first form an object with wire frames that are then covered in high quality plaster with the porcelain then glued on top, which is a method that helps to ensure longevity.

When it comes to these carvings, you’ll have to keep in mind that what you’ll see really depends on the specific kind of building you’re looking at, and where you are, as the decorative elements tend to vary between different regions in Taiwan. With a wide variation of decorative elements, what you’ll see depicted on a Buddhist temple, Taoist temple, or even on a mansion may include some of the following elements:

Human Elements: The Three Stars (福祿壽), Magu (麻姑), the Eight Immortals (八仙), Nezha (哪吒), the Four Heavenly Kings (四大天王), Mazu (媽祖), Guanyin (觀音), and depictions of stores from the ‘Romance of the Three Kingdoms’ (三國演義) and the ‘Journey to the West’ (西遊記), etc.

Animals and Mythical Creatures: Phoenixes (龍鳳), dragons (龍), peacocks (孔雀), Aoyu (鰲魚), carp (鯉魚), Qilin (麒麟), lions, elephants, tigers, leopards, horses, etc.

Floral and Fruit Elements: Peonies (牡丹), lotuses (蓮花), narcissus flowers (水仙), plum blossoms (梅花), orchids (蘭花), bamboo (竹子), chrysanthemum (菊花), pineapples, wax apples, grapes, etc.

While some of these elements are quite straight-forward, quite a few of them are completely foreign to people who aren’t from Taiwan, so I’ll offer an introduction to some of the most important of the ‘Cut Porcelain’ decorative elements.

The Three Stars (三星 / 福祿壽)

One of the more common roof-decorations you’ll find in Taiwan are the depictions of the three elderly figures at the top-center of a swallowtail roof. Known as the ‘Sanxing’ (三星), which is literally translated as the ‘three stars’, you might also hear them referred to as ‘Fulushou’ (福祿壽), a Mandarin play-on words for ‘Fortune’, ‘Longevity’ and ‘Prosperity’.

In this case, Fu (福), Lu (祿), and Shou (壽) appear as human-like figures and are regarded as the masters of the three most important celestial bodies in Chinese astrology, Jupiter, Ursa Major and Canopus. When you see the ‘Sanxing’ on top of a temple, they appear as three bearded wise men. Coincidentally they might also look a bit familiar to the average observer as ‘Fuxing’ (福星) is depicted as Yang Cheng (楊成), a historic figure from the Tang Dynasty, while ‘Luxing’ (綠星) is represented by the ‘God of Literature’ (文昌帝君), and Shouxing (壽星), who is represented by Laozi (老子), the founder of Taoism.

Within Chinese iconography, these ‘three wise men’ are quite common, and their images can be found throughout China, Vietnam and South East Asia. Here in Taiwan, you’ll most often find them adorning the apex of a Taoist or Taiwanese Folk Religion Temple.

The Double-Dragon Pagoda (雙龍寶塔)

Known by a number of names in both Mandarin and English, the ‘Double-Dragon Pagoda’ (雙龍寶塔) or the ‘Double Dragon Prayer Hall’ (雙龍拜塔) is essentially a multi-layered pagoda that is similarly placed at the top-center of a Buddhist temple, or a mixed Buddhist-Taiwanese folk-religion place of worship.

As usual, while acting as a decorative element, the pagoda also represents a number of important themes - it is used as a method of ‘warding off evil spirits’ and for disaster prevention, in addition to representing both filial piety and virtue. For Buddhists in particular, pagodas have been important buildings with regard to the safe-keeping of sacred texts, so having the dual dragons encircling the pagoda in this way can also be interpreted as ‘protecting the Buddha’ or ‘precious things’.

Whenever you encounter a temple with one of these Double-Dragon Pagodas, if you look closely, the pagoda will have several levels, with two green dragons on either side, or encircling it. In Mandarin, there’s a popular idiom that says “It is better to save a life than to build a seven-level pagoda” (救人一命、勝造七級浮屠), so having the dragons protecting the pagoda speaks to the salvation one might receive while visiting the temple as it is protected by dragons from the heavens. That being said, the number of levels you see on the pagoda is also quite important as the number of levels indicates the rank of the deity enshrined within the temple.

Double-Dragon Clutching Pearls (雙龍搶珠)

One of the other common images depicted in the center of a roof of a temple is the ubiquitous ‘Double-Dragon Clutching Pearls’ design. However, unlike the two mentioned above, when it comes to the dragons clutching pearls, there is a wide variation of designs, so even though it’s a common theme found on Taoist places of worship, you may not encounter the exact same design very often. Nevertheless, no matter how they might vary in appearance, what always remains the same is that there will be a glowing red pearl in the middle with dragons on either side.

Originating from an ancient folklore story, the image of two dragons surrounding a pearl is something that you’ll find not only on temples like this, but in paintings, carved in jade, and various other forms of artwork.

The origin of the story is a long one, so I’ll try my best to briefly summarize how the image became popularized - essentially, a long time ago, a group of fairies were attacked by a demon while resting near a sacred pond only to be saved by a pair of green dragons. When the ‘Queen Mother of the West’ (王母娘娘) heard about this, she gifted the two dragons with a golden pearl that would grant one of them immortality.

Neither of the dragons wanted to take the pearl, showing great humility to each other, so after a while the Jade Emperor (玉皇) gifted them a second pearl. Afterwards, the dragons devoted their immortality to helping others, and used their power to send wind and rain to assist with the harvest.

Thus, when it comes to this particular image, what you’ll want to keep in mind is that they are meant to highlight themes of ‘harmony’, ‘prosperity’, ‘humility’, ’good luck’ and the ‘pursuit of a better life,’ which makes them a perfect addition to a place of worship.

Dragons and Aoyu (雙龍 / 鰲魚)

In addition to being featured at the top-center of a roof, you’ll also find cut-porcelain depictions of dragons located in various other locations on the exterior of a Hokkien-style building. By this point, I’d only be repeating myself if I went into great detail about the purpose of the dragons, but it’s important to note that the ‘dragon’ is something that is synonymous with traditional Chinese culture, and given that people of Chinese ethnic origin consider themselves to be ‘descendants of the dragon’ (龍的傳人), and the emperors themselves regarded as reincarnations of dragons, they are particularly important within the cultural iconography of the greater-China region.

In the English-language, dragons are merely dragons, but in Mandarin, there are a multitude of names to describe these mythical creatures in their various forms. Similarly, for most westerners, dragons are regarded as fire-breathing monsters, but within Chinese culture, their roles are completely reversed. Dragons are noted for their power over water and nature, and instead of being aggressive creatures that bring about death and destruction, they’re known for their good deeds.

Most commonly found adorning the main ridge and at both of the ends, the cut-porcelain depictions of dragons that you’ll encounter on roofs in Taiwan are often the most complex decorative elements on a building and are meant to symbolize power, enlightenment and protection, especially with regard to their ability to prevent fire. The most common dragon that you’ll find adorning the roofs of Taiwan’s places of worship are of the ‘hornless-dragon mouth’ or ‘chiwen’ (鴟吻) variety. Translated literally as ‘owl mouth’, this type of dragon is known as one of the ‘Nine Dragons’ (九龍), each of which are known for specific protective functions. In this case, ‘chiwen’ dragons are known for their affinity for swallowing things, especially fire. They’re depicted as hornless dragons, with fish-like, truncated bodies, large wide-open mouths, and colorful scale-like spikes all over their bodies.

That being said, if you look closely at the ‘dragons’ that adorn the top of temple roofs, you might notice that they’re not always of the ‘chiwen’ variety and are often a complex fusion of other mythical creatures. While these creatures almost always appear with a dragon’s head, fooling most people, you’ll find that they may also feature the body of a phoenix, tortoise, horse, etc.

Similarly, sometimes what you might think is a dragon actually isn’t a dragon at all.

Which to tell the truth, can often be quite confusing if you’re not adept at examining the finer details of these decorative elements.

Even though these other creatures appear dragon-like, especially with regard to the ‘chiwen’ variety, its very likely that you’ve encountered another common variety of Hokkien cut-porcelain decorative elements. Depicting a mythical creature known as an “Aoyu” (鰲魚), these creatures feature a dragon head and animal body fusion. An ‘Aoyu’ is basically a ‘carp’ that is in the process of transforming into a dragon. With one foot in the door regard to the transformation process, an Aoyu features the head of a dragon, but maintains the body of a fish. Similar to the role that the chiwen play, you’ll often find Aoyu featured on both of the ends of the roof’s ridge as they’re likewise known for their ability to ‘swallow fire and spit water’ meaning that they’re also there to offer protection to the temple.

Of all the cut-porcelain art that you’ll find decorating places of worship in Taiwan, you’ll probably notice that the dragons are often the most complex in terms of their design and the attention to detail that goes into crafting their images. The complexity of the dragon’s head and the spiky-scales on their bodies require a tremendous amount of work, which should highlight just how important they are.

Cut-Porcelain Decorative Murals

While the larger cut-porcelain decorative elements are much easier to identify, you’ll also notice that there are smaller, yet very elaborate mural-like decorations located along the roof’s main ridge, on the ridge platform and on the lower sections of the roof. Even though almost every place of worship in Taiwan features these types of murals, they are often quite small, and you have to look very carefully to actually identify them. If you find yourself traveling the country with a local friend, unless they’re a temple experts, it’s safe to say they won’t be much help in identify what story these murals are depicting, which is part of the reason why these things can be so confusing. If you find yourself really interested in knowing exactly what was going on, you’d be better off asking one of the temple volunteers inside, or trying to find the information online.

Even though there is a wide variation of stories that each of these murals depict, they generally illustrate the following themes: Mythology (神話), events from the Investiture of the Gods (封神演義), events from the Spring and Autumn Period (春秋時期), events from the Chu–Han War (楚漢戰爭), events from the Romance of the Three Kingdoms (三國演義), events from the Journey to the West (西遊記), Buddhist stories (佛的故事), and finally, Taiwanese Folklore Stories (台灣神明傳說).

To highlight the complexity of identifying what these murals depict, if I use the ‘Romance of the Three Kingdoms’ as an example, the novel is over 800,000 words long, features 120 chapters, and more than a thousand characters. So, even if someone tells you that the mural is depicting a story from the novel, you’d have to be quite well-versed in Chinese Classics to be able to identify the specific event.

However, when it comes to the local stories that you’ll find depicted on these buildings, you’re going to find murals depicting events in the lives of the most popular religious figures in Taiwan, and those that hail from the Hokkien homeland. Some of these stories are likely to include: Mazu conquering Thousand-Mile-Eye and Wind-Following Ear (媽祖收千順二將軍), Mazu Assisting Koxinga (媽祖幫助鄭成功), Tangshan Crosses the Taiwan Strait (唐山過臺灣), the Eight Immortals Depart and Travel to the East (八仙出處東遊記), the Eight Immortals Cross the Sea (八仙過海), etc. Similarly, it’s important to note that while these events are often depicted with the help of Hokkien cut-porcelain art, you’ll also find them carved into wood, painted on walls, and carved in stone.

If you’ve ever seen a Lonely Planet, or any travel guide about Taiwan for that matter, its very likely that you’ve seen a photo of one of a cut-porcelain dragon in the foreground with Taipei 101 in the background. While it may seem cliche at this point, the mixture of these two elements helps to illustrate both the traditional and modern fusion of contemporary life in Taiwan today.

The Hokkien people make up an estimated seventy-five percent of Taiwan’s population today, so even though it may seem like they are the predominant cultural force on the island, its also important to remember that the modifications that have been made to their style of design over the years have adapted elements of Taiwan’s other cultural groups, including the island’s Indigenous people, the Hakka’s, etc.

What you’ll see in Taiwan today, while similar to that of Southern Fujian is a style of architectural design that has been refined to meet the needs of the people of Taiwan, and thus, no matter where you fall on the argument of ‘Hokkien vs. Taiwanese’, it goes without saying that this style of design has become ubiquitous as an aspect of the cultural identity of the Taiwanese nation today.

Obviously, as I mentioned earlier, this article is only touching on the top of the iceberg when it comes to this topic. Sadly, it remains a topic that isn’t widely accessible in the English-language, and information tends to be hard to come by. Still, I hope it helps clear up any questions any of you may have with regard to what you’re seeing when you visit a temple or historic building in Taiwan during your travels. If not, feel free to leave a comment, or send an email, and I’ll do my best to answer any other questions you may have.

References

Taiwanese Hokkien | 臺灣話 (Wiki)

Hokkien culture | 閩南文化 (Wiki)

Hokkien Architecture | 闽南传统建筑 (Wiki)

Architecture of Taiwan | 臺灣建築 (Wiki)

台灣建築裡的秘密:從天后宮到行天宮,每間寺廟都是活生生的台灣移民史 (Buzz Orange)

台灣傳統民居簡介 (文山社區大學)

最常見的動物裝飾 (老古板的古建築之旅)

台灣民間信仰 (Wiki)