One of the best ways to know what people are looking for when they visit this site is to make use of analytics tools made available to developers that analyze what visitors are looking for when they arrive. Sometimes though, I don’t really have to bother spending time looking at these things as people are often a little more direct, and when I don’t have what they’re looking for, they get in touch. Needless to say, over the years, I’ve discovered that in both cases the most important area where this site is lacking is on the subject of Taiwan’s most iconic tourist destination, Taroko Gorge.

So, when I receive emails asking: “Why can’t I find anything on here about Taroko Gorge?”, I can completely understand your frustration; I’ve been writing travel blogs about Taiwan for several years now, but have avoided the topic for far too long.

In my defense, there are actually a few reasons for this:

There are already some great travel guides dedicated to introducing Taroko.

I tend to focus on some of Taiwan’s lesser-known tourist destinations.

However, the main reason why I’ve avoided the topic is that I’ve always been of the opinion that when I did publish something about Taroko that it would have to be an extensive travel guide that encompassed the most popular stops within the National Park, as well as those that are considered much less accessible. I’ve always considered Taroko Gorge to be a subject that required a considerable amount of dedication, and until I was ready, I wasn’t really comfortable with putting anything out there to compete with what is already available. I also wanted to compile a large collection of photos from my many visits to the area to ensure that I had all my bases covered and would be able to provide a travel guide that I wish I could have had when I first visited the area well over a decade ago.

Ultimately, I’ve started to change the way I approach this blog and have come to the conclusion that any guide that I write about Taroko would essentially be a ‘work-in-progress’ article requiring regular updates, and a web of links to individual articles about the popular destinations with the massive park.

Taroko is deservedly one of Taiwan’s most popular tourist destinations and even though there is far too much to cover in any one guide, or any one visit - I think it’s best to start with some basics and build from there.

I’m not going to make any bold claims that this will an ultimate travel guide, but I will continue to update this space with new information, new photos and new destinations as time goes by, and hopefully at some point it will become a useful tool for anyone wanting to get the most out of their visit to one of the most beautiful natureal tourist destinations in Taiwan, if not the world.

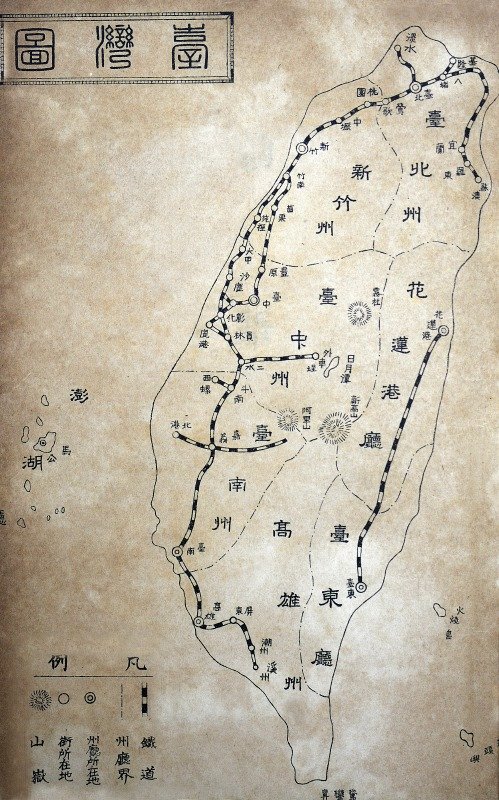

Taroko National Park (太魯閣國家公園)

Whenever I write an article, I like to start out with a bit of an introduction of the history of whatever I’m writing about. When it comes to Taroko though, that is a little more difficult as the origin of the gorge dates back to the origin of this beautiful island itself.

Essentially both Taroko Gorge and the rest of the island made its first appearance nearly four million years ago when the Philippine and Eurasian tectonic plates forced this absolutely beautiful landmass out of the Pacific Ocean in spectacular fashion.

Over the span of that several million year history, Taroko Gorge has been in a constant state of geological change as shifts in the tectonic plates have gradually reshaped the land in addition to natural forces such as earthquakes, typhoons and natural erosion which have taken part in shaping the rock walls and the landscape within the gorge.

Located on the East Coast of Taiwan, Hualien (花蓮) is one of the most geologically active areas in the country due to its proximity to the volatile Ring of Fire. That being said, Hualien’s proximity to what geologists refer to as a ‘subduction zone’ comprised of the two tectonics plates mentioned above, means that it would be an understatement to say that the area is no stranger to earthquakes. This is why you’ll find that the earth seems to be pretty busy moving around whenever you’re in the area. Fortunately for us, this is simply a natural method for the earth to release energy and it shouldn’t deter anyone from visiting the area, as this has been something people have had to put up with for as long as Hualien has been settled by humans.

It’s also one of the reasons why Taroko Gorge, and many other areas along Taiwan’s East Coast are so damned beautiful.

I suppose you could say that one of the most amazing things about those four million years of geological activity is that the changing faces of Taroko Gorge revealed a treasure of unimaginable proportions - The geological pressure that forced the island to emerge from the ocean has been a constant thing, with the land mass being pushed a few millimeters further out of the ocean as each year passes. So, in conjunction will all of this tectonic activity, millions of years of erosion revealed one of the largest deposits of marble in the world.

More specifically, you’ll find high concentrations of stone that are composed primarily of gneiss, green schist and metamorphic limestone, which is more commonly known as marble - in addition to granite and quartz, all of which works together to present a wide range of vivid natural colors, especially within the gorge.

While all of the rocks are pretty important, the Grand Canyon wouldn’t be as ‘grand’ if it weren’t for the Colorado River, and Taroko likewise wouldn’t the same without its Tkijig River (塔次基里溪), better known today as the Liwu River (立霧溪). Originating at an elevation of over three thousand meters high in the mountains, the beautiful river flows down into Tianxiang (天祥) and then into the gorge before emptying into the Pacific Ocean.

Today, Taroko National Park is recognized as one of Taiwan’s nine official National Parks and spans an area of 920 km2, encompassing land in Hualien (花蓮縣), Nantou (南投縣) and Taichung (台中縣).

The park is home to a considerable amount of flora and fauna as well as twenty-seven mountains over three thousand meters high, or around twenty percent of Taiwan’s one hundred highest peaks.

Link: 100 Peaks of Taiwan | 台灣百岳

Modern development in Taroko started during Taiwan’s Japanese Colonial Era (1895-1945) with the area becoming important for the extraction of natural resources. Once there was enough infrastructure in place, the Governor Generals’s Office established the Tsugitaka-Taroko National Park (次高タロコ國立公園) in 1937 (昭和12年), which was (interestingly) much larger than the park of today as it also included Tsugitakayama (次高山), known these days as Snow Mountain (雪山), Taiwan’s second highest peak.

The Taroko National Park as we know it today was established almost half a century later in 1986, and it seems like ever since then the area has been in a perpetual state of construction as the infrastructure within the park has never been adequate enough to accommodate for the amount of tourists wanting to visit, especially during weekends and national holidays. Fortunately, it seems like those problems have finally been solved and the park has become much more accessible than ever before as the problem with traffic jams on the narrow mountainous roads has been addressed by the government.

I could keep going into further detail about the origin of park, but I’m going to stop here and focus on something much more important - The name “Taroko” (太魯閣) is derived from the indigenous peoples who made the area their home thousands of years prior to the arrival of any other humans to Taiwan.

The Truku (太魯閣族), who are often also referred to as the “Taroko” people are one of the sixteen (currently) recognized groups of Indigenous peoples in the country, and it doesn’t matter what colonial power controlled Taiwan, the area has been a part of their ancestral home for thousands of years.

It’s important to remember that even though we’re able to enjoy the beauty of Taroko today. It’s theirs.

Link: Taiwanese Indigenous Peoples | 臺灣原住民族 (Wiki)

That being said, the changing eras in Taiwan have seen changes within the gorge - for example, when the Japanese controlled Taiwan, you’d find Shinto Shrines - These days you’ll find Buddhist temples and churches. The further you travel up into the mountains beyond all the tourist destinations however, you’ll start to find where the real inhabitants of Taroko have made their homes for the past few thousand years.

With that in mind, many of the tourist destinations and hiking trails within Taroko National Park have been given Mandarin names, reflecting Taiwan’s current (colonial) status, but its important to note that the vast majority of what we are able to enjoy today was once the territorial hunting grounds for the Truku people, who graciously share their homeland with the people of Taiwan, and the rest of the world today.

Note: As I introduce each of the National Park’s various tourist destinations below, I’ll do my best to include the original name of each of these locations, even though the current Mandarin names are often just transliterations.

It goes without saying that any visit to Taiwan should include a trip to the East Coast, so that you can experience the beauty of Taiwan. Even if you’re only in the country for a short period of time, a trip to Taroko should be on the top of your list of places to visit. I’ve personally been to the gorge well over a dozen times, and it never gets old. More importantly, even after visiting so many times, I’ve still only seen a fraction of what this massive National Park has to offer.

Things to see and do within Taroko National Park

If you haven’t already, Taroko National Park is the kind of place that’ll make you fall in love with Taiwan, and the great thing about this massive park is that one visit will never suffice!

Sure, you could do the typical day-trip thing and check out all the most popular sights, but if you’re able to invest a bit more time, you could easily spend days in the park and never grow tired with all the hiking trails, hot springs, camp grounds, luxury hotels, and so on.

For first time visitors, a trip to Taroko can be an overwhelming experience due to the sheer size of the park. This is why planning a trip can be overwhelming, especially international tourists who have a difficult time reading Mandarin. To solve this problem, Taroko National Park has been divided up into four different regions: Taroko Recreation Area, Bulowan Recreation Area, Tianxiang Recreation Area, and the Hehuan Mountain Recreation Area.

For most visitors, especially those who are day-tripping from Hualien, the majority of time spent within Taroko will be done between the Taroko Recreation Area and the Tianxiang Recreation Area. However, given that the highway can take you across the Central Mountain Range to the western side of Taiwan, Hehuan Mountain is also an option.

That being said, most people prefer to enjoy that portion of the park from the Nantou side on a different trip.

Before I go into detail about some of Taroko National Park’s most popular attractions, I think it’s a good idea to provide a list of what you’ll find within each of the four designated areas of the park.

As this article is updated over time, I hope to provide photos and descriptions of each of these locations.

Until then, you’ll find each of them marked on the map that I’m including below.

Taroko Recreation Area (太魯閣遊憩區)

The Taroko Recreation Area of the National Park is the lowest portion of the park and essentially acts as the entrance, and your introduction to the rest of the park. This area stretches from the coast of Hualien where you’ll find the Qingshui Cliffs and the area where the Liwu River empties into the sea. Within this area you’ll find several hiking trails, temples, the headquarters of the National Park, quite a few restaurants and even more hotels.

Qingshui Cliffs (清水斷崖)

Taroko Visitor Center (太魯閣遊客中心)

Changchun Shrine (長春祠)

Changuang Temple (禪光寺)

Shakadang Trail (砂卡礑步道)

Bulowan Recreation Area (布洛灣遊憩區)

Once the home of a Truku Village, the Bulowan Recreation Area is separated by an ‘upper terrace’ and ‘lower terrace’, and is where the vast majority of day-tripping tourists visiting the National Park will spend most of their time. The lower terrace area has traditionally been the most popular with tourists, but over the past few years the ‘upper’ area has started to compete for attention with its beautiful suspension bridge, and the celebration and promotion of indigenous culture and history. Within this area you’ll not only find Taroko’s most popular tourist stops, but some of the best hiking trails in the park.

Zhuiliu Cliffs (錐麓斷崖)

Zhuiliu Old Road (錐麓古道)

Bulowan Village (布洛灣臺地)

Shanyue Suspension Bridge (山月吊橋)

Swallow Grotto (燕子口)

Jinheng Park (靳珩公園)

The Tunnel of Nine Turns (九曲洞)

Tianxiang Recreation Area (天祥遊憩區)

For most tourists, the Tianxiang Recreation Area is the end of the line when it comes to a day-trip adventure through Taroko National Park. This is the area where traffic is easily able to turn around and head back down through the gorge, and also a pretty good spot to get out, stretch and check out some of the attractions within the small village. Tianxiang is home to one of Taiwan’s most expensive luxury hotels, a beautiful Buddhist monastery, several hiking trails, wild hot springs, etc. So even though some might consider this area a simple area to turn around and head back down the mountain, you’d be missing out on quite a bit if you didn’t explore for a while!

Xiangde Temple / Tianfeng Pagoda (祥德寺 / 天峯塔)

Wen Tianxiang Park (天祥公園)

Tianxiang Youth Activity Centre (天祥青年活動中心)

Huoran Pavillion (豁然亭)

Wenshan Park (文山公園)

Baiyang Trail (白楊步道)

Water Curtain Cave (白楊步道水濂洞)

Hehuan Mountain Recreation Area (合歡山遊憩區)

The Hehuan Mountain Recreation Area is the highest portion of the National Park, and is located in a different county than the rest of the park. As mentioned above, the vast majority of tourists who visit this area are arriving from the opposite side of Taiwan than the rest of the park, and are usually staying for a few days. This area of the park is known for its hiking trails and the ability to actually drive your car or scooter to some of the highest elevated roads in Taiwan.

Wuling (武陵)

Hehuan Mountain (合歡山)

Now that we have this list out of the way, I’m going to start going into more detail about some of the most popular stops listed above, and then I’ll move onto some of the places that most of the day-trippers miss, due to a lack of time.

Eternal Spring Shrine (長春祠)

The Eternal Spring Shrine is one of those iconic picturesque locations within Taroko Gorge, and is often either the first or last stop on most people’s trip through the gorge. The shrine, which can been seen from a distance from the highway is located on the side of a mountain across the Liwu River and features a two-kilometer hiking trail that brings you through the mountain to the temple and beyond.

The shrine is dedicated to the 226 workers who perished during the construction of the Central Cross-Island Highway, and was originally constructed in 1958 - however the temple that you see today is actually the third iteration as landslides have destroyed the temple on two separate occasions.

Even though there is a long hiking trail around the temple, the walk from the parking lot to the temple itself is actually only around three hundred meters, so don’t be afraid to visit. It’s actually pretty close and the walk to the shrine through a cave and a tunnel constructed within the mountain is pretty cool.

As most of you know, I’m a pretty big fan of Taiwan’s temples, but when it comes to this one, I think it looks best from a distance rather than up close. When you are viewing the temple from the parking lot or the road, it looks beautiful with the Changchun Waterfall (長春瀑布) flowing through the middle of the shrine.

When you get closer though, you its just not the same. I highly recommend taking lots of beautiful photos of the shrine from a distance - and I do think everyone should make the effort to walk through the cave.

One thing that you’ll have to keep in mind about the hike however is that the trail is often closed due to falling rocks. I’ve been to the shrine probably half a dozen times over the years, and unfortunately have never had the luck of going when the trail to the bell tower above was open. If you’re lucky to visit when its open, I highly recommend completing the hike!

Swallow Grotto Trail (燕子口)

The Swallow Grotto trail is one of Taroko Gorge’s most popular tourist stops, and is part of an absolutely beautiful narrow section of highway that allows tourists to walk along parts of the old road, with one-way traffic driving nearby. The trail derives its name from the swallows that are constantly flying around the grotto, nesting within conveniently located potholes (壺穴) within the side of the mountain on the opposite side of the Liwu River.

The beginning of the trail is located near the entrance of the popular Zhuilu Old Road (錐麓古道) trail, and follows the highway up the mountain. The beautiful thing about the walking sections of the grotto is that you get to walk through the caves constructed for the original highway, with the steep mountain on both sides, and the Liwu River running through a narrow valley below, making for absolutely stunning photo opportunities. Even though the area is quite narrow within the grotto, you’ll feel quite small yourself as you are looking over the edge of the mountain at the beautiful marble rock-face in addition to the emerald green river below. Likewise, many of the caves that you walk through are dark and damp and are perfect places to cool off on hot days.

As you walk through the grotto, it’ll eventually open up to a wider valley area where visitors are able to park their car, and where you’ll also find Jinheng Park (靳珩公園). Within the park you might find some vendors selling food and drinks, but more importantly there is a public restroom for visitors.

On that note, if you’re driving a car, stopping and getting out near the grotto can sometimes be a little difficult, especially if you’re visiting on a busy weekend or during a national holiday. The park area might be your best option for stopping and getting out, but it also fills up pretty quickly and you’ll have to put your parallel parking skills to the test.

Another thing you’ll want to keep in mind is that (although it’s not entirely necessary) you may also want to pick up one of the free safety helmets at the National Park Headquarters before visiting the grotto as there are frequent rockslides, especially within the dark cave areas.

The Tunnel of Nine Turns (九曲洞)

Arguably one of the top tourist stops within Taroko Gorge, the Tunnel of Nine Turns has seen considerable investment and an impressive upgrade in the condition of this absolutely stunning pedestrian walking trail in recent years. A few years back when I first visited Taroko, the trail was showing signs of age and there was always the threat of falling rocks - but that didn’t stop people from visiting as it is one of the best areas to enjoy the beauty of Taroko Gorge.

These days, the newly upgraded trail has been made considerably safer, and I have to say the end result looks eerily similar to a Bond villain’s secret lair. Closed to the public for around six years, the trail is considered an engineering marvel given all the work that went into its restoration. With that in mind, walking this trail is something that every visitor to Taroko must do now that it is finally reopened to the public.

Even if you’ve only planned a half-day trip through the park and you only end up visiting one or two locations, you can rest assured that if one of them is this walking trail, you’ll be absolutely amazed at the beauty of the gorge as it offers some pretty amazing vantage points and you’ll leave content with your visit!

The walking trail only takes only about half an hour to compete (not including the amount of time you’ll be taking photos) and leads you through a narrow part of the gorge where the Liwu River winds through the valley around several corners, with steep marble walls on both sides. Not only are the vantage points to enjoy the gorge beautiful, but the tunnel itself, which weaves through beautiful well-lit caves.

If you’re lucky enough to visit when the park isn’t busy, you’ll not only enjoy the beauty of the gorge, but also natural silence as all you’ll hear as you walk through the caves are the sounds of the river flowing through the gorge below, and birds flying around.

What you’ll want to keep in mind about the Tunnel of Nine Turns, whether you’re driving a car, or a scooter is that there is only one entrance and exit to the newly restored trail. This means that when you walk the trail, you’ll also have to leave the same way you came. Arguably though, this is a pretty good thing as it gives you two different perspectives of the trail.

Just a healthy reminder, if you are visiting on the weekend or during a National Holiday, finding parking for a car near the tunnel can be a little difficult, and it will test your parallel parking skills in the process.

Water Curtain Cave (白楊步道水濂洞)

One of the more popular places to visit in Taroko as of late is the Baiyang Water Curtain Cave, a picturesque tunnel where you’ll be showered with natural spring water. The Water Curtain Cave is located within the Baiyang Hiking Trail (白楊步道), just past Tianxiang and is roughly a three-hour round-trip hike that allows you check out a large two-tiered waterfall in addition to the Instagram-famous cave.

While the cave itself is beautiful, there is quite a lot to see along the hiking trail, but its important to remember that you’ll need to bring along a flashlight, raincoat and waterproof footwear as its the kind of trail where you’re going to get wet!

Xiangde Temple / Tianfeng Pagoda (祥德寺 / 天峯塔)

One of the most vivid memories of my first few months in Taiwan are from my first trip to Taroko Gorge, and more specifically walking around Xiangde Temple. It was the trip that likely cemented my love affair with this country.

The Buddhist temple is located high atop a mountainous crag just as you cross the Pudu Bridge (普渡橋) into Tianxiang (天祥) and while I was walking around the temple grounds on a beautifully sunny day, a cloud of mist suddenly rolled in and enveloped the entire mountaintop where we were exploring.

It felt a bit like a scene straight out of a movie and made our visit to the temple much more special.

In the years since, the temple has changed quite a bit with restoration and renovation projects undertaken to ensure that the half century-old temple remains intact.

During my most recent visit to the temple, they were busy constructing a new more accessible pathway to the temple, repairing their giant Buddha statue, as well as the pagoda.

To reach the temple, you first have to walk across a beautiful pedestrian bridge that crosses the Liwu River from the highway. Once you’re on the other side, you have to walk up a very steep set of stairs until you reach the next level, where you’ll find vegetarian restaurants, and a small store where you’re able to purchase drinks while chatting with the monks and nuns who live at the temple. From there, you’ll have to make your way up another set of stairs to reach the temple and the pagoda, which is thankfully situated on a flat section of land.

I will caution you that the stairs to the temple are quite steep, but don’t let that deter you - you’d be missing out if you skipped the temple because of some stairs.

Xiangde Temple was constructed in 1968, and is known for having one of the highest-elevated statues of Ksitigarbha (地藏), a popular Buddhist figure in East Asia. The temple has a beautiful exterior, while the interior is a simple space with meditation cushions on the floor. Nearby you’ll find the Tianfeng Pagoda, which in the past was open for guests to climb to the top, but these days is most often closed for safety reasons.

One thing you’ll want to keep in mind though is that unlike most temples in Taiwan, this one is actually a functioning monastery with a group of Buddhist monks and nuns living in the dorms next to the temple. So, even though the temple is a popular tourist attraction, it’s important to remember to keep your voice down and follow any of the rules they have posted at the front entrance.

Tianxiang Recreation Area (天祥)

Tianxiang Village is pretty much the final stop for most people traveling through Taroko.

The village is essentially one of the best areas along the highway to stop, have a snack, use the bathroom, and then turn your vehicle around and head back down through the gorge. That being said, Tianxiang isn’t just a place where you should stop before heading back down as there are quite a few things to see within the historic village.

Within the village you’ll find a tourist visitor centre, luxury hotel, hostels, restaurants and bus stops. You’ll also find hiking trails, gardens, two historic churches and the ruins of a former Shinto Shrine, among others.

Originally named Tapido (塔比多) in the local Truku language, the village was (somewhat absurdly) renamed “Tianxiang” in honor of a Song Dynasty (宋朝) hero named Wen Tianxiang (文天祥) who helped in the battle against Kublai Khan (元世祖).

What relation did a guy who died in China more than a thousand years ago have to do with this area?

Very little. It’s just another leftover from Taiwan’s legacy of colonialism.

The Shinto Shrine that once existed within the village (another remnant of a past colonial era) was demolished and converted into the Wen Tianxiang Park (文天祥公園), a memorial space that retains much of its original layout.

Some of the things you’ll find within Tianxiang:

Tianxiang Plum Garden (天祥梅園)

Tianxiang Catholic Church (天祥天主堂)

Wen Tianxiang Park (文天祥公園) - Formerly Sakuma Shinto Shrine (佐久間神社)

Baiyang Hiking Trail (白楊步道)

Huoranting Hiking Trail (豁然亭步道)

Lushui Wenshan Trail / Hot Spring (綠水文山步道/溫泉)

Tianxiang Youth Activity Centre (天祥青年活動中心)

Silks Place Taroko Hotel (太魯閣晶英酒店)

Bulowan Village / Terrace (布洛灣山月吊橋)

Bulowan Village, located high above the cross-island highway is one of the more recent additions to the list of attractions within the National Park. The area was once home to a former settlement of Truku Indigenous people, and today is a large open space that celebrates Indigenous culture with educational resources to help tourists to learn more about the history of the area.

While up on the Bulowan Terrace, you’ll find the Bulowan Service Center (布洛灣遊憩區), the Bulowan Visitor Center (布洛灣管理站), the Shanyue Suspension Bridge (山月吊橋) and the Taroko Village Hotel (太魯閣山月村).

Arguably this area is relatively new, and not so well advertised - If it weren’t for the beautiful suspension bridge that crosses the Liwu River just above of Swallow Grotto, I think most people wouldn’t even really notice that it exists. You would be missing out though if you didn’t take the opportunity to head up to the terrace, check out the suspension bridge and take the opportunity to learn more about the culture and history of the Truku people.

If you’d like to cross the Shanyue Suspension Bridge, you’ll have to keep in mind that there is an online application process to go through before you’re able to visit. Visiting the bridge is free, but there is a quota for each of the four daily sessions that allow tourists to cross.

Link: Booking Guidelines for Shanyue Suspension Bridge (Taroko National Park)

Qingshui Cliffs (清水斷崖)

While not located within the ‘Taroko Gorge’ area, the iconic Qingshui Cliffs are still part of Taroko National Park, and if you’re visiting the gorge, you might as well visit the cliffs as well, right?

There are a couple of areas where tourists can stop to enjoy the stunning natural beauty of the Qingshui Cliffs, each of which offer tourists with unique views at varying elevations.

If you’re interested in learning more about the areas where you can enjoy the cliffs, I recommend checking my article that is entirely dedicated to visiting them.

Link: Qingshui Cliffs (清水斷崖)

Hiking Trails within Taroko National Park

Arguably, one of the most rewarding experiences any visitor can have while touring Taroko National Park is hiking one of the more than a dozen hiking trails available to tourists. Within the park we are blessed with trails that range from being short and sweet to those that require an investment of several days.

But how is one to figure out which are family friendly and which are better suited to experienced hikers?

Well, one of the areas that has been covered quite well with regard to Taroko National Park on the internet are its hiking trails. So, when planning a trip to the area, its important to do some research beforehand so you can decide which hiking experience will be best for you. Likewise, one of the things that you’ll want to keep in mind is that the environment at Taroko can sometimes be a little unstable due to earthquakes, typhoons and erosion, so if you’re planning a hike, you might be sorely disappointed when you arrive and find out that the trail is closed for repairs.

Fortunately, the Taroko National Park website is an excellent resource that provides frequently updated information (in both Chinese and English) about the trails and should be able to prevent you from the disappointment of finding a ‘Trail Closed’ sign when you arrive at the park.

Link: Taroko National Park Trails (太魯閣國家公園步道列表) - English | 中文

Sadly, one of the areas where the English-language information is lacking is with regard to the parks six official trail ‘difficulty levels’, which are actually very important for anyone wanting to visit.

Below, I’ll explain each of the levels, what you’ll need for the hikes, and list each of the trails within that particular difficulty level so that you’ll better understand what you’ll need to visit.

I’ll also provide links to the official Taroko National Park English and Chinese language pages about each of the trails where you can find out real-time info about their condition and whether or not they’re currently open and if trail requires hikers apply for a permit before entering, I’ll add a star next to them.

If the trail does require a permit before hiking, you can easily visit the Taroko National Park Headquarters, Tianxiang police station, or apply on the Taroko National Park Website.

Link: Trails, Campgrounds and Bed Availability (Taiwan’s National Parks)

Note: There are some discrepancies within the official literature with regard to the level of difficulty of some of the trails between the English-language and Chinese-language lists. I’ve gone ahead and used the Chinese-language list as it is very likely the most accurate and should ensure that you don’t come across any unexpected issues.

Level 0 (第0級)

Description: The easiest of the trails within the park, mostly flat and well maintained. open for all ages and also wheelchair and baby carriage accessible.

Requirements: Water, rain gear, cellphone

Level 1 (第1級)

Description: Well-maintained trails with adequate signage available for hikers. These trails generally aren’t very steep, and can be completed within several hours. Open for hikers of all levels of experience.

Requirements: Water, rain gear, cellphone

Level 2 (第2級)

Description: The trail is well-maintained but there are several slopes and potential risks for hikers. These trails can generally be completed within a day, and are open for hikers of all experience, but those in good shape are preferred.

Requirements: Water, rain gear, cell phone, quick-dry clothing, hiking bag

Dekalun Trail (得卡倫步道) - English | 中文

Level 3 (第3級)

Description: The trails are maintained, but are in remote mountainous areas and feature steep slopes and frequent weather changes. The time it takes to complete these trails varies, but generally anywhere between one to three days is to be expected. Hikers should be experienced and travel in groups.

Requirements: Water, rain gear, cell phone, quick-dry clothing, hiking bag, camping gear

Level 4 (第4級)

Description: The trails are located in remote mountainous areas with a mixture of maintained paths, rugged terrain and steep slopes. These trails take anywhere between three to five days and hikers should be relatively experienced, travel in groups and be capable of performing first aid.

Requirements: Water, rain gear, cell phone, quick-dry clothing, hiking bag, camping gear

Level 5 (第5級)

Description: The trails are located in remote mountainous areas with limited cellphone reception, the paths are rugged and there are steep slopes that are considered quite dangerous. The climate in the area tends to change frequently, so hikers should be well-prepared. These hikes generally take about three to five days and require hikers to camp and be capable of carrying heavier bags as well as traveling in groups in addition to applying for permits.

Requirements: Water, rain gear, cell phone, quick-dry clothing, hiking bag, camping gear

Before I move on, I think its important to mention that in years past you could visit Taroko and easily find a camping spot along the river, go swimming, river tracing, or enjoy one of the wild hot springs.

You might have heard from friends that Taroko is a pretty cool place for all of these things, and yes it’s true - its great for these things. Unfortunately in recent years the government has cracked down pretty hard on these activities, so if you’re found swimming in the river, or enjoying one of the hot springs, its likely that you might be fined.

One would hope that the government might see the error in its ways with regard to banning these outdoor activities, but until then it’s probably best not to violate the rules. If none of that worries you, please be careful.

Getting There

Marked on the map above are almost all of the points of interest within Taroko National Park.

The question however is, how do you actually get there? And when you’re there, how do you get around

There are a number of methods for which you can tour the park, and even though I have my own preferred methods, others might disagree. Its a very subjective argument!

Taroko is easily accessible with a train station nearby, so if you’re planning a visit you have the option of making use of buses, cars, scooters, or bicycles. If you were brave, you could even walk through the gorge, but that wouldn’t exactly be the most efficient use of your time.

Suffice to say, Taroko National Park is (for the most part) located in Northern Hualien County (花蓮縣), and day trips to the area most often use Hualien City as a starting point given that it is much more convenient to start a tour of the park early in the morning after waking up in an accommodation nearby.

With several flights and even more trains out of Taipei daily, Hualien is quite accessible from the capital - that being said, even though it takes a bit longer, you’d certainly be missing out if you didn’t take the railway option as the views on the train along the east coast railway are absolutely stunning.

Flights to Hualien

Taipei Songshan Airport - Hualien Airport (台北松山機場 - 花蓮航空站)

Flights out of Taipei’s Songshan Airport are serviced by UNI-Air (立榮航空)

Taipei 7:10 - Hualien 8:00 (Monday to Saturday)

Taipei 19:20 - Hualien 20:10 (Daily)

Taipei 12:00 - Hualien 12:50 (Sundays)

Return flights

Hualien 8:35 - Taipei 9:25 (Monday to Saturday)

Hualien 20:40 - Taipei 21:40 (Daily)

Hualien 13:20 - Taipei 14:10 (Sundays)

There are also flights out of the airports in Taichung and Kaohsiung, but they are infrequent (twice a week) and are much more expensive, so I recommend just taking a train instead.

The prices for flights tends to fluctuate, but they’re actually not that expensive, so if you are willing to pay a bit more, you can generally take flights there and back for less than $3000NT.

I’m not particularly sure the time you spend checking in for the flight and the security screening process is actually worth taking the forty minute flight when you consider that the train only takes three hours.

Trains to Hualien

Taking the train to Hualien right now is an experience that I think every person who travels to Taiwan should experience at least once. As I mentioned above, the train ride along Taiwan’s east coast is absolutely stunning. That being said, in recent years the time it takes to get there from Taipei has been drastically reduced thanks to improvements in the railway infrastructure.

Options for the train range from the slower local trains (區間車) and the Tze-Chiang (自強號) and Chu-Kuang (莒光號) limited-express trains to the newest additions, the Puyuma (普悠瑪號) and Taroko (太魯閣號) Express trains, both of which have reduced the travel time by at least an hour.

And fortunately for travelers, all of these trains conveniently stop at both Hualien Railway Station (花蓮車站) as well as Xincheng Railway Station (新城火車站), which is the station closest to Taroko National Park.

Car

If you’re traveling in a group, driving a car through the park is a pretty good option.

Years ago, I would have never recommend driving into the gorge, but the traffic situation within the busiest sections has improved considerably, thanks to the construction of several new tunnels that separate traffic on the narrowest sections of highway. This make driving a car slightly more tolerable, but if you’re visiting during a holiday, it’s likely that you’ll still get stuck in a traffic jam.

That being said, one of the reasons why I don’t actually recommend driving a car into the park is due to the fact that you’ll end up missing a lot due to the inability to stop whenever you feel like it.

There are so many areas along the highway where you’ll want to stop to take photos, but when you’re in a car you’d end up causing a major traffic jam if you did - and you might even end up on TV as the asshole of the day.

Likewise, finding parking spots within the gorge, especially at the most popular stops can be difficult, and will put your parallel parking skills to the test.

If you don’t have your own vehicle, cars can be easily rented once you’ve arrived in Hualien near both of the train stations mentioned above.

You’ll need to have a local license or a valid international drivers license however to rent one.

Scooter

Personally, I’d argue that the best way to enjoy Taroko Gorge is to first make your way to Hualien, and then renting a scooter. I’d argue that riding a scooter through Taroko offers tourists quite a few benefits that includes being able to stop pretty much whenever you want, but also giving you a better sense of the immense size of the gorge while riding through it.

Unfortunately for foreign tourists, the various scooter rental shops in Hualien have become strict with their rental policies, so if you don’t have a local drivers license or an International Drivers License, you might not have much luck finding a scooter to rent.

It was explained to me by the rental place that I frequent near Hualien Train Station that foreigners often “have no idea how to ride a scooter” and when they’re rented out, they come back half destroyed, or end up being involved in a traffic accident. This has led quite a few of the rental places to not want to take the risk. There are of course work-arounds for this, but you may want to have a back up plan just in case you can’t get a scooter.

I recommend checking the two links below for a more detailed explanation of the scooter rental situation in Hualien.

Links: Scooter Rental in Taiwan (Foreigners in Taiwan) | Exploring Hualien with a Scooter (The Spice to My Travel)

While this would be my personal preferred method of transportation while in Hualien, I have a Taiwanese scooter license, so it is considerably easier for me to rent scooters. I’m not going to recommend any specific places to rent one, but you will find several near Hualien Station and Xincheng Station that offer a variety of scooters for travelers. The prices might be slightly more expensive during weekends and national holidays, but generally speaking you can rent a scooter for around 450-600NT per day, which isn’t different from most other areas of Taiwan.

Cycling

For cyclists, Taroko has become an extremely popular destination in recent years and the local government has made cycling through the National Park even more convenient by allowing travelers to take their bicycles on (certain) trains. Likewise, you’ll find several professional bike rental shops in Hualien City as well as in Xincheng that allow for short-term rentals.

If you are planning to cycle through Taroko, I highly recommend renting your bike near Xincheng Station rather than cycling directly out of Hualien considering that it takes more than an hour from the city to the park compared to the fifteen minutes it takes from the latter.

The prices of rentals varies, but you’ll find that most bikes go for around $250NT per day, which isn’t that bad.

Like scooters, cycling allows travelers to stop pretty much anywhere they like along the road through Taroko Gorge, but I imagine the twenty or so kilometer journey up the mountain isn’t the easiest if you’re not in good shape, or an experienced cyclist. Likewise, the highway becomes quite narrow in a few sections, so cyclists should be wary of traffic, especially on weekends or national holidays as there will be a number of tour buses sharing the road.

Bus

For those travelers who don’t have access to their own means of transportation, taking a bus through the gorge might be one of your only options. That being said, taking the bus tends to be slow, inconvenient, and requires considerably planning to ensure that you get the most out of your trip through the park.

If the bus is your only option, you’re going to have to plan a schedule and keep track of all of the times to ensure that you don’t find yourself waiting around for too long. This means that when you stop at a place like Swallow Grotto, you’ll have to keep track of your time to ensure that you don’t miss the bus on the other side.

It’s also important to note that the buses that travel through the gorge start at Hualien Train Station and only go as far as Tianxiang, where they’ll turn around and head back down the mountain.

So, if you’re planning on hiking one of the trails beyond there, you’ll have to walk to the trailheads.

Taiwan Trip (台灣好行) - Taroko Route (太魯閣線) Day Pass: $250NT

Taroko Bus (太魯閣客運) - #302

Hualien Bus (花蓮客運) - #1126, #1133, #1141

All of these buses will also stop at Xincheng Train Station (新城火車站), so if you want to save some time you might want to hop on one of the buses from there.

You should also become familiar with the iBus info System website, which is available in both English and Chinese, and will help you schedule your routes and know where the bus is in real time. There are likewise some apps that you can download for your phone to help you with the bus schedules, but most of them are only available in Chinese.

For more detailed information about the buses and how and where you can purchase tickets, I recommend checking out the link below from the official Taroko website.

Link: Bus Timetable (Taroko National Park)

Accommodations in Hualien

Last, but not least - You’ve planned a trip to Hualien to check out Taroko and some of the other cool things to see in the area. But now you have to ask yourself, where will you stay? Should you stay in Hualien City to be close to all the action? Or should you stay close to Taroko so you can spend as much time as possible in the National Park?

When it comes to planning where to stay during your trip to Hualien, it can become a bit of a headache for travelers as there are a number of options, but some of them fill up quite quickly, and the closer you get to Taroko, the more expensive they become.

Likewise, the closer you stay to the train station in Hualien, the more expensive your accommodation will be. That being said, no matter where you stay in the area you’ll be able to find a wide range of accommodations from inexpensive hostels to premium five-star hotels.

With this in mind, what you’ll want to take into consideration when deciding where you’ll stay is how you plan on getting around Hualien and what your budget is. To put it simply, if you have access to your own means of transportation, be it car or scooter, you can easily find a place at your preferred price range.

If however you plan on making use of public transportation, your choices will become a bit more limited.

Personally, I’ve always elected to stay in an accommodation close to Hualien Station as I always rent a scooter when I’m in the area. What I tend to look for in a place to stay however is likely a bit different than others, so I recommend taking some time to research places to stay.

While planning your trip, I recommend checking out AirBnB, booking.com, Agoda, Trip Advisor where you’ll be able to find some of the best places to stay in the area.

References

Taroko National Park | 太魯閣國家公園 (Wiki)

A Guide to Taroko Gorge and Taroko National Park (Nick Kembel)

Taroko National Park - Taroko Visitor Center (Taiwan Travel)

Taroko Gorge (Foreigners in Taiwan)

太魯閣歷史影像敘事 (ARCGIS)