This post is the third and final part of a long-planned three part series on Longgang (龍岡), a culturally and historically significant section of Zhongli, the city I’ve called home for the past decade.

The first part of the series served as an introduction to the area itself and explained why it is a bit different than your average Taiwanese town while the second part focused on the beautiful mosque that serves the people of the community.

Part 1: Longgang | Part 2: Longgang Mosque

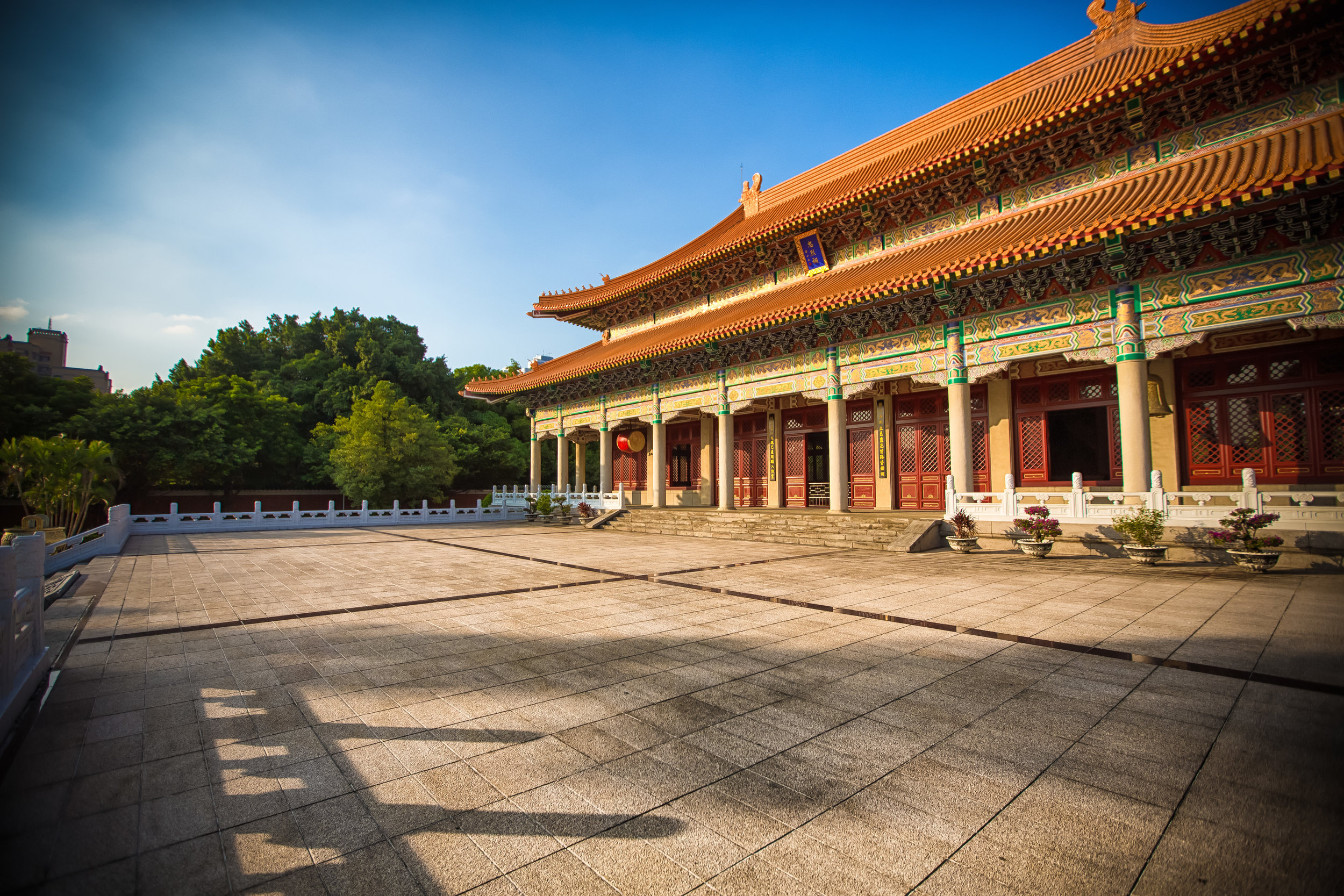

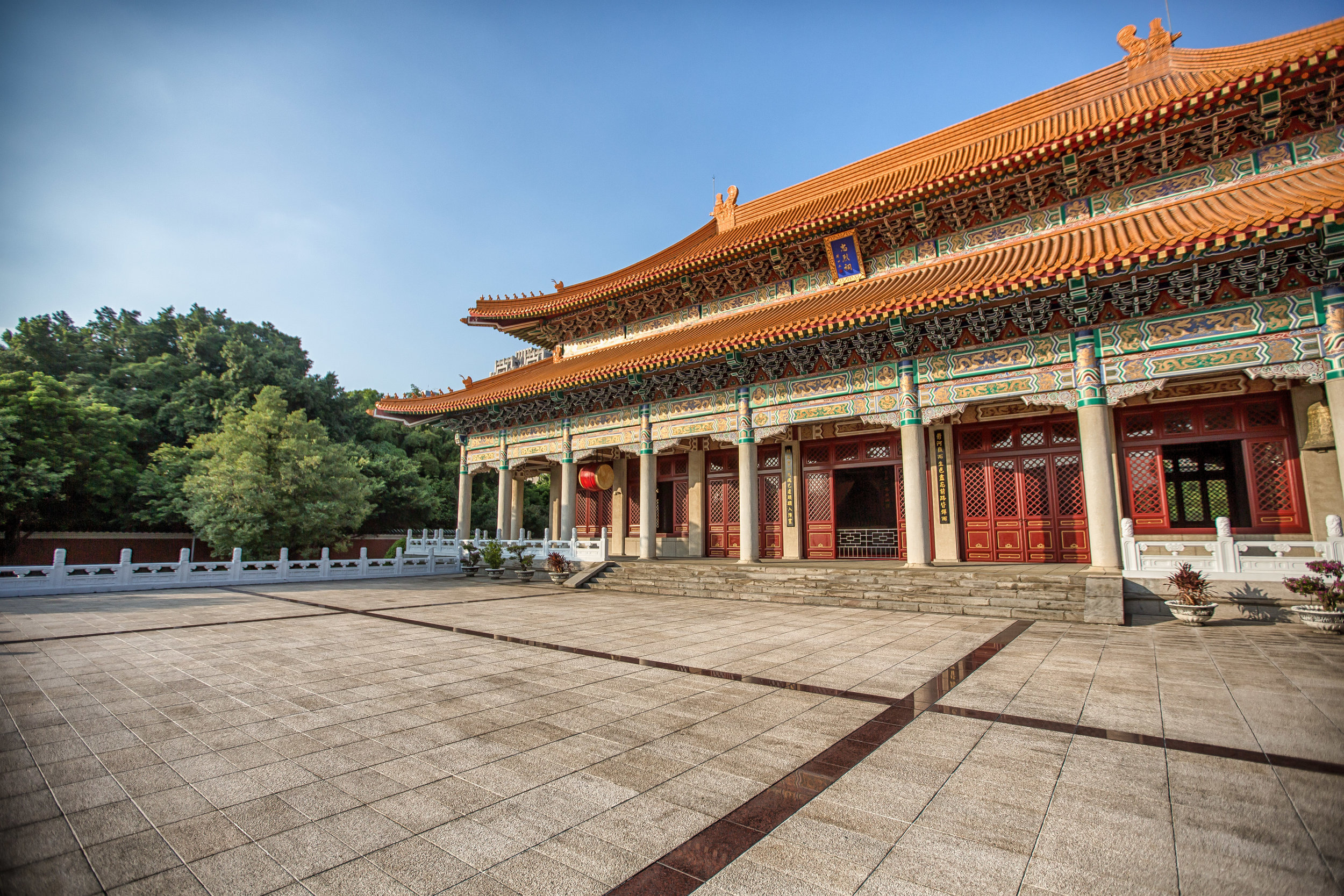

This post will focus on Mazu Village (馬祖新村), a newly restored Military Village that has become a beautiful art space for the youth of Taiwan. The village is also one of the focal points for the revitalization of the Longgang area which has gone through a tremendous transformation over the past few years.

Taoyuan was once home to over ninety military communities but only three of them remain with Mazu Village being one of the best representations of what life was like in one of these historic communities. The village today is not only an excellent place to attend community events, art exhibitions and film festivals but also an excellent reminder of Taiwan’s recent history.

Military Villages (眷村)

When the Chinese Nationalists retreated to Taiwan at the end of the Chinese Civil War (國共內戰) they brought with them over two million refugees who were in quick need of places to stay.

Most of the people who were able to make the journey from China could do so because they were part of the social elite or members of the Republic of China Armed Forces.

The new arrivals learned quickly that the government clearly wasn’t prepared to house them, so plans were made to hastily construct shoddy villages which would serve the purpose of 'temporarily' housing until they could return to their homeland when the communists were defeated.

Or so was the plan.

The villages which are known as Military Dependents' villages (眷村) were constructed all over Taiwan in the 1940s and 1950s for members of the military and their families.

The Nationalist pipe dream was that they would only retreat to Taiwan and regroup for a short time in order to retake China from the communists. Unfortunately that would never come to pass and these so-called 'temporary' villages became 'permanent' settlements for the less privileged of those refugees.

The villages ended up becoming important centres for the preservation of traditional Chinese culture, art, literature and cuisine.

Despite the refugees receiving preferential treatment from the government, the homes were sloppily put together and were properly of the state which meant that the tenants had no possibility of land ownership. Tenants did their best to improve their living situations but as Taiwan's economic miracle was taking place the villages started to become abandoned as people looked for a better life elsewhere.

As more and more of the homes were abandoned and left to the elements it seemed as if the people who remained were living in government-owned slums. The government thus decided to improve the public-housing situation and tear down the majority of the villages which would be replaced with modern high-rise apartments.

In the past I blogged about the Rainbow Village (彩虹村) in Taichung, a military village that was set to be demolished for urban renewal. One of the tenants however took it upon himself to transform the decaying remains of the village into his own personal art project in an attempt to save his home from being destroyed. The village became a popular tourist attraction and has so far saved it from destruction.

Society has taken interest in the preservation of the remaining villages and civil groups have been set up to protect them (as well as other places of historical value like the Losheng Sanitorium (樂生醫療院)). These groups have become somewhat of a thorn in the side of the government and in some cases the public pressure they have applied has forced the government to come up with other ideas.

Unfortunately the future of many of Taiwan’s remaining Military Communities is still undecided - with almost 90% of them already a faded memory, its important that the few that remain are preserved to ensure that these important pieces of Taiwan’s history are preserved for the enjoyment of future generations.

Mazu Village (馬祖新村)

Mazu village was originally constructed in 1957 (民國46年) as a community to house the soldiers and families of the 84th Army Division (陸軍第84師). The village gets its name from the division which was originally stationed on the ROC-controlled Mazu Islands (馬祖列島) off of the coast of China's Fujian province.

At its peak, the village had 226 homes, stores, restaurants, a traditional market, kindergarten, movie theatre, park, etc. Mazu Village was home to around 1700 people for several decades but most of them were eventually resettled into modern public housing nearby.

As the people who lived in the community started to move away, the village, like a lot of other military communities entered into a period of decline and looked like it was about to meet the same fate as many of the others.

The Longgang (龍崗) area of Zhongli is one that is rich in military history with a large base, an army training school. It is also home to an interesting range of restaurants where you'll find a fusion of Chinese and South East Asian fare.

Longgang was home to not only Mazu Village, but also several other military communities that sprouted up around the military bases and the former airforce base.

By the turn of the century however most of those villages were deserted and were bulldozed with only Mazu village being chosen for preservation.

A visit to one of these villages brings a feeling of nostalgia for some in Taiwan, especially those who were brought up in these communities - Even though they are becoming somewhat of an endangered species these days, when one of them is restored as an art space or park, it has the ability to attract quite a few visitors looking to learn a little about Taiwan's modern history.

They also offer older generations a way of explaining to their young people of Taiwan how good they have it now compared to how it was when they were growing up.

Parents in Taiwan can't say that they 'walked to school barefoot in 50cm of snow' like mine did in Canada, so having living proof of what life in Taiwan was like in the past is a great way to educate young people.

In some cases however the villages that get redeveloped into modern spaces, like the "4-4 South Village" (四四南村) in Taipei, become somewhat kitschy and lose their old-school feeling. The restoration process of Mazu Village though was done in a way that allows people to have a taste of both the community’s history and its future.

Mazu Art Village (馬祖新村眷村文創園區)

When I first learned that Mazu Village was being restored, I went over to check out what was happening. The village at the time was becoming a bit of a hit on Instagram with people heading over to take photos at the entrance of one of the homes.

What I found when I arrived however was that the local government only opened up a single home to the public as a preview of what was to come when the project was completed.

I figured it wouldn’t take that long for the whole community to open up, so I wrote up a blog post and left it in the queue until the day that the community was once again open to the public.

I waited for a year, and then another and it seemed like the village wasn’t ever going to reopen.

Then in late 2017 (after almost giving up) the village suddenly reopened and started hosting cultural events on weekends.

The village is now home to a public space known as the “Mazu Art Village” which aims to become home to ‘cultural creative markets’ where artists and designers will be invited to set up exhibitions and art spaces to promote their work.

In addition to the opening of the village, the former activity centre (across the street from the entrance) has been transformed into the Taoyuan Arts Cinema (桃園光影電影館) which will focus on the history of Taiwanese cinema and hold public showings of some of the nation’s best films.

In recent years the Taiwanese government both at the national and local levels have invested quite a bit of time and money in transforming older spaces like Mazu Village into tourist attractions while at the same time offering spaces to the young artists and designers of the country to promote their work.

The formula that has been successful at Taipei’s Treasure Hill (寶藏巖) and the Huashan Creative Park (華山1914文化創意產業園區) has been followed here at Mazu Village and is hopefully one that will provide the creative people of Taoyuan a place to promote their work while at the same time allowing this historic village to once again thrive.

Getting There

If you are travelling from outside of Taipei, the easiest way to get to the village is to hop on a bus at the bus station near Zhongli Train Station. You can take bus 112 (South), 115, 5008, 5011 or 5050 from there and get off at the Mazu Village stop. The village is a short walk from there.

Address: 桃園市中壢區龍二街252號

The village and Art Cinema are open Tuesday - Sunday from 9:00-5:00 and 1:00-9:00 respectively.

Even though the renovation and restoration work at Mazu Village isn’t 100% complete, the village has reopened to the public and from now on will hold regular hours for visitors.

As both a historic village and an Art space, the village offers quite a bit for visitors to check out and a visit in conjunction with the special culture and cuisine of Longgang will make for an interesting day if you are coming from other parts of Taiwan.

If you are interested in some of the events that take place at the village, make sure to follow their Facebook Page or check their website for updates!

Facebook: 馬祖新村眷村文創園區

Website: 桃園眷村鐵三角

Gallery