When I arrived in Taiwan, I wasted little time getting myself a scooter.

When you’re not living in Taipei, a scooter is probably one of the most important purchases you’ll make during your time in Taiwan and once I got one, a whole new world of exploration opened up for my friends and myself.

On one of our earlier scooter expeditions, we set off for a place in Taoyuan to check out the night view of the Taoyuan cityscape on the top of Tiger Head Mountain (虎頭山).

Having arrived a couple of hours before sunset, we noticed a sign for the Taoyuan Confucius Temple (桃園孔廟) and decided to stop in and check it out. After that we started making our way up towards the mountaintop when I noticed an old stone post on the side of the road that read “Taoyuan Martyrs Shrine” (桃園忠烈祠).

I stopped the convoy scooters and ran up the set of stairs to check out what was at the top.

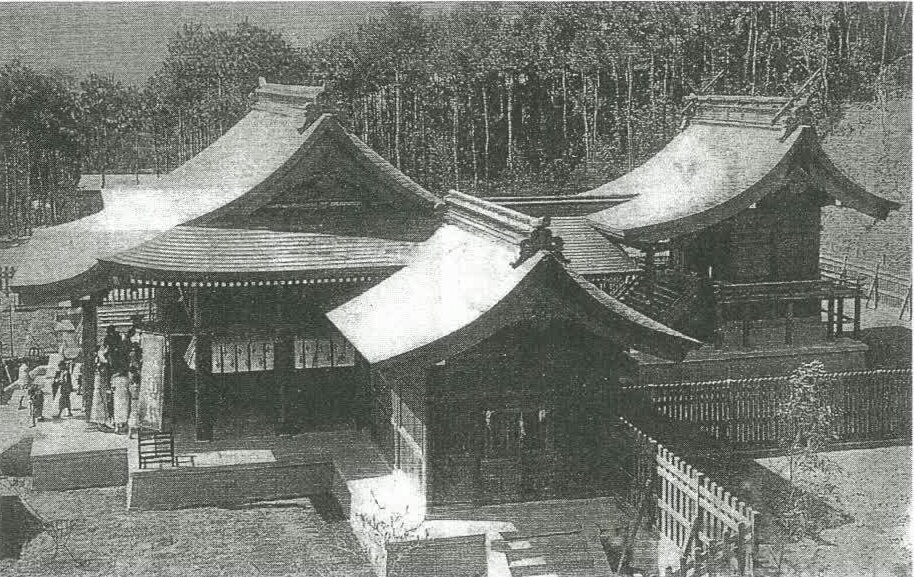

Surprisingly, I found a beautiful (but somewhat unkept) Japanese-looking shrine.

As the years passed, I went back to visit quite a few more times and ended up writing a blog about it, which was one of my first on the subject of Japanese Colonial Era buildings.

Then the shrine closed for an extended period of restoration and during those years, I started to write write extensively about other shrines like this around the country, and ended up coming to the conclusion that the information that I offered readers in this one just wasn’t good enough.

So now I’m back, with an updated version that has more information and new photos.

And just to warn you, I’m not going to be brief on the information. This is going to be a deep dive into the history and architecture of this historic shrine.

Which is why I’m going to be splitting it into two different articles.

Before I start though, let me take a minute to explain something I think is important.

If you’re looking for this shrine elsewhere on the web, you’ll find it in most places officially named the “Taoyuan Martyrs Shrine” (桃園忠烈祠). Honestly though, the latter is a role that has significantly diminished in recent years, especially after the current administrative restructuring and period of restoration that took place. So, I’m going to try to refer to it as the “Taoyuan Shinto Shrine” (桃園神社).

This isn’t a political stance, nor is it a knock on its current role as a Martyrs Shrine, it’s because this shrine is the one of the worlds most well-preserved and most complete Shinto Shrines outside of Japan.

I’d be remiss though if I didn’t mention that one of my projects in recent years has been to visit Taiwan’s Martyrs Shrines and chronicle their history. This isn’t because I have an affinity for war-memorials, it is because the majority of these shrines were once home to some of Taiwan’s largest Shinto Shrines, like this one. If you’d like to learn more about Taiwan’s various Martyrs Shrines, I recommend taking a look at my article about the National Revolutionary Martyrs’ Shrine in Taipei, where I take a deep dive into the history of these shrines and provide links to the other Martyrs Shrines/Shinto Shrines that I’ve already covered.

Taiwan was once home to over two hundred Shinto Shrines of all shapes and sizes but only a handful of these shrines continue to exist. The Taoyuan Shinto Shrine, unlike so many others has been fortunate to have been able to stand the test of time and is now one of the nation’s most significant windows into an important period of its modern history.

Another thing that you should know is that as of this update, I’ll be splitting the article into two. This part will focus only on the history of the Shinto Shrine and the Martyrs Shrine while the second part will provide an in-depth description of its architectural design how to get there.

I hope that you find all of this interesting enough to read both parts.

Taoyuan Shinto Shrine (桃園神社 / とうえんじんじゃ)

Before we get into the history of the shrine, we have to talk a bit about a few important events that took place prior to its construction.

During the Japanese Colonial Era, Taiwan was divided into eight different administrative districts, Taihoku (台北州), Karenko (花蓮港廳), Taito (台東廳), Takao (高雄州), Tainan (台南州), Taichu (台中州), Hoko (澎湖廳) and Shinchiku (新竹州).

The “Taoyuan” as we know it today was simply a district within Shinchiku (しんちくしゅう), named Toengai (桃園街 /とうえんぐん) and included these four villages:

Rochikusho (蘆竹庄), currently Luzhu District (蘆竹區)

Osonosho (大園庄), currently Dayuan District (大園區)

Kizansho (龜山庄), currently Guishan District (龜山區)

Hakkaisho (八塊庄), currently Bade District (八德區)

Note: It is interesting to see that the majority of the names of these districts have been kept more or less the same, save for the conversion to Chinese pronunciation.

As “Toen” at that time was an administrative district under Shinchiku, it didn’t actually require a large Shinto Shrine as the Shinchiku Shrine (新竹神社 / しんちくじんじゃ) had it covered. Smaller neighbourhood shrines, like the Luye Shinto Shrine in Taitung, would have been sufficient and quite a few of them were constructed around the prefecture.

Link: List of Shinto Shrines in Taiwan | 台灣神社列表 (Wiki)

That was until 1934 (昭和9年), when the colonial government passed a resolution that every village and town should have its own shrine (一街庄一社), which started the process of constructing shrines all over Taiwan, and is why (you’ll see in the link above) most of the larger shrines in Taiwan were constructed between 1934 and 1945.

This policy of constructing shrines all over Taiwan was the precursor to a much more nefarious decision that the government would take just a few years later to forcibly convert the entire population into Japanese subjects who were loyal to the empire and State Shinto.

Officially starting in 1936 (昭和11年), the "Kominka" policy (皇民化運動), which literally means to “force people to become subjects of the empire,” is more commonly known today as “Japanization” or forced assimilation. This was essentially one of the most desperate attempts by the Japanese, who were embroiled in war across Asia, attempting to expand their empire.

The policy expanded upon the mere construction of Shinto Shrines to converting or destroying local places of worship, enforcing strict language polices, requiring people to take Japanese names and instituting the “volunteers system” (志願兵制度), drafting Taiwanese into the Imperial Army.

Link: Japanization | 皇民化運動 (Wiki)

The Taoyuan Shinto Shrine, like so many of its contemporaries around Taiwan was constructed just as these policies started to take root and was tasked with assisting in ‘uniting’ the people and inspiring Japanese patriotism, or the "Japanese spirit, " known as Yamato-damashii (大和魂).

When the shrine was constructed, it was one of hundreds that were built around the island to help ease the population with their transition into life as citizens of the Japanese empire.

Today, less than a handful of them remain in existence.

Planning for the Taoyuan Shinto Shrine started in 1935 (昭和10年), and was designed by Haruta Naonobu (春田直信), a well-known architect and founder of the Haruta Architecture Company (春天建設) in Nagoya.

While Haruta’s architectural design stuck to a traditional Japanese layout, the buildings at the shrine feature what could be argued a ‘fusion’ of Chinese design that dates back to the Tang Dynasty (唐朝) with that of Japanese Nagare-zukuri (流造) design.

It would be an understatement to say that Japanese architecture has been highly influenced by that of the architecture of the Tang, so it wasn’t very likely an obvious nod on the part of Haruta to design the shrine in this way, which could be argued represented the heritage of the people who lived here prior to the arrival of the Japanese.

The shrine was constructed facing the south-west and in a direct axis of the Taoyuan Train Station (桃園車站), which showed the importance of the station as the heart of the town and Japanese style urban development.

As a show of the relationship between Taiwan and the rest of Japan, the shrine was constructed with a mixture of cypress (檜木) from the mountains of central Taiwan as well as Japanese cedar (日本柳杉).

The shrine officially opened on June 6th, 1938 (昭和13年) and took the 12 petal chrysanthemum (十二菊瓣) as its official emblem, something I’ll talk a bit more about later.

As a Prefectural Level Shrine (縣社), the Taoyuan Shinto Shrine was the largest of all the shrines in the Taoyuan area and was home to full-time priests and administrators who lived on-site.

And even though it only operated for less than a decade before the Colonial Era came to an end, it was an important place of worship for the people of Taoyuan.

Given its importance, the shrine consisted of the following:

A Visiting Path or “sando” (參道 /さんどう)

Stone Lanterns or “toro” (石燈籠/しゃむしょ)

Stone Guardian Lion-Dogs or “komainu” (狛犬/こまいぬ)

A Sacred Horse or “shinme” (神馬 / しんめ)

A Public Washroom or “tousu” (東司/とうす)

Staff Dormitories (管理室/神職人員宿舍)

Shrine Gates or “torii” (鳥居 /とりい)

An Administration Office or “shamusho” (社務所/しゃむしょ)

A Purification Fountain or “chozuya” (手水舍 /ちょうずや)

A Middle Gate or “chumon” (中門 / ちゅうもん)

A Hall of Worship or “haiden” (拜殿 /はいでん)

A Main Hall or “honden” (本殿/ほんでん)

The Taoyuan Shinto Shrine was likewise home to several important deities enshrined within with Main Hall, including the Three Deities of Cultivation, Toyoke no Omikami, Emperor Meiji and Prince Kitashirakawa Yoshihisa.

The Three Deities of Cultivation (かいたくさんじん / 開拓三神)

The Three Deities of Cultivation, consist of three figures known for their skills with regard to nation-building, farming, business and medicine.

The three “Kaitaku Sannin” are as follows:

Ōkunitama no Mikoto (大國魂大神 / おおくにたまのかみ)

Ōkuninushi no Mikoto (大名牟遲大神 / おおなむちのかみ)

Sukunabikona no Mikoto (少彥名大神 / すくなひこなのかみ)

While these deities are also quite common among Japan’s Shinto Shrines, they were especially important here in Taiwan due to what they represented, which included aspects of nation-building, agriculture, medicine and the weather.

Given Taiwan’s position as a new addition to the Japanese empire, ‘nation-building’ and the association of a Japanese-style way of life was something that was being pushed on the local people in more ways than one.

Likewise, considering the economy at the time was largely agricultural-based, it was important that the gods enshrined reflected that aspect of life.

Toyoke no Omikami (豐受大神 / トヨウケビメノカミ)

The female deity ‘Toyoke no Omikami’ is a deity that hails from Japanese mythology known simply as the Japanese ‘Goddess of Food,’ but is more specifically referred to as the Goddess of Agriculture and Industry. Residing at the Ise Grand Shrine (伊勢神宮), the goddess is known to provide food for her counterpart, the sun goddess Amaterasu (天照大神).

The first mention of these four deities was in the “Birth of the Gods” (神生み) section of Japan’s all-important ‘Kojiki’ (古事記), or “Records of Ancient Matters”, a thirteen-century old chronicle of myths, legends and early accounts of Japanese history, which were later appropriated into Shintoism.

Emperor Meiji (明治天皇)

Emperor Meiji was the 122nd Emperor of Japan and one of the most consequential, presiding over an era of rapid change in the country that saw Japan transform from a feudal state with no connection to the outside world to an industrialized world power.

Considered one of the greatest emperors in Japanese history, the 45 year-long Meiji Era (明治) is fondly remembered for its political, social and economic revolutions, bringing Japan out of the dark and cementing its footing as a major world power.

Having presided over the Sino-Japanese war that resulted in the Treaty of Shimonoseki (下關條約), Emperor Meiji added Taiwan and the Penghu Islands to his empire in 1895, starting what would become a fifty year of colonial rule of the islands.

Upon his death in 1912 (明治42年), the emperor was deified and the Meiji Shrine (明治神宮) was constructed in his honour, which consequently became one of the most important shrines in Japan, and was constructed using cypress exported from Taiwan.

Link: Meiji Emperor | Meiji Shrine (Wiki)

As the emperor who oversaw Taiwan’s addition to the empire and the first two decades of its modern development, it should be no surprise that his worship would be included in most of Taiwan’s largest shrines.

Prince Kitashirakawa Yoshihisa (北白川宮能久親王)

Interestingly, the Meiji Emperor wasn’t the only member of the Japanese royal family who was enshrined within the Taoyuan Shinto Shrine. Prince Yoshihisa, a western educated Major-General in the Japanese imperial army was commissioned to participate in the invasion of Taiwan after the island was ceded to the empire.

Unfortunately for the Prince, he contracted malaria and died in either modern day Hsinchu or Tainan (where he died is disputed), making him the first member of the Japanese royal family to pass away while outside of Japan in more than nine hundred years in addition to being the first to die in war.

Shortly after his death he was elevated to the status of a ‘kami’ under state Shinto and was given the name “Kitashirakawa no Miya Yoshihisa-shinno no Mikoto“, and subsequently became one of the most important patron deities here in Taiwan, as well as being enshrined at the Yasukuni Shrine (靖國神社) in Tokyo.

Link: Prince Kitashirakawa Yoshihisa (Wiki)

The Taoyuan Martyrs Shrine (桃園忠烈祠)

When the Japanese surrendered to the allies at the end of the war, control of Taiwan was ambiguously handed over to Chiang Kai-Shek (蔣中正) and the Republic of China.

The Sino-Japanese War had caused a lot of resentment for the Japanese among the Chinese population and upon arrival in Taiwan, both the leaders of the ROC government in China and the refugees who eventually came to Taiwan had a difficult time understanding why so many people here looked upon their period of Japanese rule with so little disdain.

In the short time that the Japanese controlled Taiwan, the colonial government developed the island's infrastructure and left the incoming regime with an almost ideal situation as they were more or less given the keys to an already established island. The problem was that the Japanese also provided education to several generations of Taiwanese citizens who ended up not really being big fans of yet another colonial regime swooping in and taking over.

It goes without saying that Taiwan’s half-century of development under Japanese rule wasn’t entirely altruistic - the colonial power, like all colonial powers benefited greatly from the resources that they were able to extract from Taiwan and the development of the island was meant to help them extract those resources more efficiently.

The development undertaken by the colonial government over its fifty year rule didn’t just include construction of island-wide infrastructure, but also provided pubic and higher education as well as the opportunity to participate in Japan’s democratic governance.

This created a class of highly educated citizens, who cherished the ideals of democratic governance.

This was a stark contrast to the corrupt totalitarian approach to governance that the Chinese Nationalist Party implemented upon arrival in Taiwan resembling the early years of Japanese colonial rule and ultimately instituted a thirty-eight year period of martial law.

The longest of its kind in the history of the world.

Link: Martial Law in Taiwan | White Terror (Wiki)

After Japan’s surrender, the new regime quickly implemented similar “kominka” style policies, like the one mentioned above. These policies included harsh language laws, punishing anyone who spoke Japanese, Taiwanese, Hakka or any of Taiwan’s Indigenous languages. Enforcement of these laws was strict and even though several generations of Taiwanese had only ever known Japanese, they were forced to quietly adapt, else they might receive a knock on the door by the Taiwan Garrison Command (臺灣警備總司令部), better known as the secret police.

Although the actual numbers of imprisonment and deaths that resulted from this long period of terror have never been confirmed, it is thought that more then 140,000 people were imprisoned and deaths range from anywhere between 5,000-30,000 people who were accused of being communist spies or their real or perceived opposition to Chinese Nationalist rule.

However even though the Chinese Nationalists spared no effort in tearing down any sign of Japanese cultural influence throughout the country, they were also faced with the very real issue of a serious housing shortage caused by bringing more than two million refugees with them from China. So even though tearing down reminders of the previous regime was a priority, they also had to be practical, allowing those refugees to become squatters in anything that provided them with a roof over their heads.

In 1950 (民國39年), shortly after Taiwan’s so-called ‘restoration’, the Taoyuan Shinto Shrine, like many of the other Prefectural Level Shinto Shrines around the island was officially converted into a “Martyrs Shrine” (忠烈祠) - a War-Memorial dedicated to the remembrance of the fallen members of the Republic of China’s Armed Forces.

As I mentioned above, one of the saving graces for this shrine was that its original construction mimicked that of Tang Dynasty-style design, so even though it was for all intents and purposes a Japanese Shinto Shrine, it wasn’t all that different from a Chinese style temple.

So with some slight changes, the shrine was easily converted into the Hsinchu Martyrs Shrine (新竹縣忠烈祠), but was later renamed when the government restructured Taiwan’s administrative districts with Taoyuan finally getting the recognition it deserves, becoming a county.

By 1972 (民國61年), when the Japanese government broke off official relations with the Republic of China, the government here reacted strongly and instituted a policy of tearing down anything remaining from the Japanese Colonial Era as a retaliatory measure.

Link: Japan-Taiwan Relations (Wiki)

The Shinto Shrines that remained were for the most part torn down and were replaced with Chinese style Martyrs Shrines.

The Hualien Shinto Shrine for example was one of the few former Shinto Shrines that retained much its original design well after the Chinese Nationalists took control of Taiwan and converted it into a Martyrs Shrine. When this policy took effect though, it was quickly torn down and replaced.

Link: 去日本化 (Wiki)

The Taoyuan Martyrs Shrine though oddly remained unscathed.

There’s no clear reason as to why it was saved from these retaliatory acts of destruction.

That being said, the Taoyuan County Government drafted plans to tear down the deteriorating Martyrs Shrine in 1985, and had an appetite to completely replace it with a Chinese-style shrine like the nearby Confucius Temple, which was under construction at the time.

Those plans met with staunch disapproval from the locals who protested the destruction of the shrine and fought to have it restored rather than torn down. The county government eventually capitulated to their demands and in 1987, after spending around $250,000 USD (NT8,860,000), the shrine was restored and reopened to the public.

In the years since, the shrine has been designated as a National Protected Historic Site (國家三級古蹟) and when Taoyuan County was amalgamated into a super city, the newly minted Department of Cultural Affairs (桃園市政府文化局) came up with a long-term plan to create a cultural park on the site.

After another two-year period of restoration, the shrine reopened to the public as the Taoyuan Martyrs Shrine and Cultural Park (桃園忠烈祠暨神社文化園區) and has become one of the most popular tourist destinations in town.

Link: Taoyuan Martyrs Shrine and Cultural Park - English | 中文 | 日文

In addition to honoring the war dead of the Republic of China’s Armed Forces, the shrine is also home to Spirit Tablets (牌位) dedicated to Koxinga (鄭成功), Liu Yongfu (劉永福) and Qiu Fengjia (丘逢甲), three historic figures who are considered important Chinese patriots in Taiwan.

The Pirate King Koxinga (鄭成功) was a Ming-loyalist who escaped to Taiwan with his fleet and established a kingdom in the south in an attempt to establish a base for which he could help to restore the Ming Emperor. His history is one that is well-told here in Taiwan and there are many places of worship throughout the country in his honour.

Link: Tainan Koxinga Shrine

Liu Yongfu was the commander of the celebrated Black Flag Army (黑旗軍), who later in life became the President of the short-lived Republic of Formosa (臺灣民主國).

Qiu Fengjia on the other hand was a Hakka poet, a renowned patriot, and the namesake for Taichung’s prestigious Fengjia University (逢甲大學).

As I just mentioned, since the most recent period of restoration, the former Shinto Shrine turned Martyrs Shrine has been converted into a “culture park” to showcase the important history of this shrine. Previously administered in conjunction with the nearby Taoyuan Confucius Shrine, today there is a lot more focus, funding and care given to the shrine.

As the most well-preserved of its size remaining in Taiwan today, it has unsurprisingly become a popular attraction with crowds of weekend travelers and the Taoyuan City Government has done an excellent job ensuring that there is a sufficient amount of literature available to guests who want to learn more about the shrine.

But even though the vast majority of the people who show up are coming for the Shinto Shrine, we still have to remember that it still serves as the official Martyrs Shrine for Taoyuan.

So remember to be respectful when you visit!

In the next part of this article, I will provide a deep dive into the architectural design of the Shinto Shrine and introduce each of the individual buildings on the site, what they’re for and their architectural design.

I’ll also provide an information about how to get there!

So, if you are interested in learning more, please feel free to continue reading!