Taipei is a dynamic city that has had a bit of success with its ability to merge modernity with its several centuries of history. Today the city is a blend of old and new where you are able to walk past century year old buildings nestled between high-rise buildings.

As a modern metropolis, the people who live in Taipei are in tune with the most cutting edge technology the world has to offer however they are not quick to forget their history and are sure to make their voices heard when pieces of the city's history are being neglected or are in danger of disappearing completely.

The voice of the people is one that was stymied for several decades during what Taiwanese today refer to as the White Terror Period (白色恐怖) where the Chinese Nationalist Government did pretty much whatever it wanted with regards to city planning and urban development. During the thirty-eight years of Martial Law (1949-1987), many of the country’s historic buildings, especially those of Japanese origin were deliberately destroyed by the Nationalist government in order to make way for modern structures.

Now that the people of Taiwan have rightfully earned their democratic freedoms, they have become very proactive in taking the government to task when it comes to the further destruction of this country’s history and the preservation of what still remains today has become extremely important for many of Taiwan’s civil society groups.

In recent years both the national and local governments have spent a considerable amount of resources to resurrect and restore some of these remaining buildings. Whether it is a Shinto Shrine, a Martial Arts Hall, Police or Teachers dorms, etc. Buildings of Japanese origin are being restored throughout the country to offer locals a glimpse into an important part of Taiwan’s history and one that has had long-lasting effects on this nation.

Link: My blog posts about buildings from the Japanese Colonial Era

Today’s post is about one of Taipei’s lesser known Japanese-era buildings and is one that has been preserved thanks to the voice of the city’s residents who stood up to protect it from disappearing forever. The 'structure' which is one of the last remaining pieces of a former Zen Buddhist Temple is a simple Bell Tower, but don’t let its simplicity fool you, there is an interesting backstory that goes with it.

Japanese Buddhism in Taiwan

The ‘Japanese Colonial Era’ (日治時代) began on April 17th 1895 when representatives from the Qing government signed the Treaty of Shimonoseki (下関条約) which signalled the end of the first Sino-Japanese War. The treaty, which is still a sour point in Sino-Japanese relations today forced the Qing empire to cede both territory and copious amounts of cash to the Japanese Empire.

When the Colonial Era in Taiwan started, the Japanese were quick to take care of any opposition to their control and also wasted no time in their effort to develop the island with modern infrastructure as well as modernizing the economy which would ultimately help contribute to the empire. As Taiwan was considered to be an important part of that empire, both strategically and economically, the Japanese took special effort to construct buildings of Japanese cultural influence while at the same time building schools, banks, roads, etc.

The buildings of Japanese cultural origin which include the various Shinto Shrines and Buddhist temples, etc. were constructed with the sole intention of helping to ‘convert’ the people of Taiwan into 'loyal citizens' of the Japanese empire who would be 'Japanese' in every sense of the term except for ancestry.

Buddhism, having established a foothold on the island several centuries earlier was one of the tools that the Japanese used to help bring the two peoples together. Initially, the Japanese brought Buddhist monks with them to serve roles in the military as chaplain-missionaries offering spiritual guidance during the initial years of the occupation.

The monks who came to Taiwan eventually began to construct language schools and charity hospitals where they would focus on improving the lives of average Taiwanese citizens as well as promoting Japanese-style Buddhism. This effort didn’t last long however thanks to the language barrier and the fact that Japanese Buddhism was viewed by the locals as a colonial system of beliefs which only benefitted the colonial power.

The lack of results in terms of cultural conversion led to funding ultimately being cut off by the Japanese central government and forced the monks who had come to Taiwan to focus less on the native population and more so on the benevolence of the Japanese people who migrated to the island.

Interestingly, even though Buddhism was originally used as a way for the colonial powers to endear themselves to the people living in Taiwan, the religion ended up becoming a tool for the people of Taiwan. The people of Taiwan, who have always been quite entrepreneurial knew that Buddhist temples were the perfect places to brush shoulders with the higher-ups in Japanese society. So, to gain political or economic favour Buddhism was often used to achieve a more prosperous life during the colonial era.

Today, a large portion of people in Taiwan, if asked would claim that they are Buddhist - The history of Buddhism in Taiwan can be a long and confusing one and despite the religion being a tool for state control (for both the Japanese and the Chinese Nationalists). The legacy of the Japanese Colonial Era can still be felt today as most of the largest Buddhist organizations operating in Taiwan adhere to the philosophy and practices of the schools of Buddhism brought to Taiwan by the Japanese.

Bell Towers / Shoro (鐘樓)

A common feature of Buddhist temples throughout Asia (and admittedly is one of the first things that comes to mind when foreigners think about Buddhist temples) is that of the sound of a gong or a bell being rung. If you’ve seen a Kung-Fu movie, its likely that you can picture that of a misty mountain with the sound of a bell ringing.

Whether its a temple high in the mountains or one in the middle of busy Taipei City, Bell Towers are a common feature among Buddhist temples. Much like the call to prayer in Islam, the Bell Towers in Buddhist monasteries serve as a way to wake monks up, summon monks to the temple, notify people of dinner, etc.

When Buddhism was brought to Japan, the practice of using a bell tower as a part of religious ceremony and temple architecture was brought over as well. In Japan, the bell towers, known as “shōrō” (鐘樓) became an important part of a temple's design and was a practice that was later integrated into Shinto temples as well.

While temple architecture in Chinese temples has traditionally been quite strict, adhering to the principles of Feng Shui, the Japanese were able to mix things up a bit and modify not only the architectural design of the bell towers but also the position for which they are located within a temple.

Japanese Bell Towers typically fall into two different types of architectural design, both of which can still be seen in Taiwan today - The first type is the most traditional variety known as “Hakamagoshi” (褲腰). This type is typically a walled two-storey hour-glass shaped building with the bell on the second floor. The second type is a newer (13th century “new”) variety known as “Fukihanachi“ (吹放ち) which is an open structure with no walls and a bell hanging in the middle. The common feature of both types of towers is that they are adorned with beautiful Japanese-style gabled (切妻造) or hip-and-gable (入母屋造) rooftops.

The bells, otherwise known as “Bonshō“ (梵鐘) typically hang from the middle of the bell tower and are cast from thick bronze. Rather than being struck from the inside like most western bells, they are struck from the outside with either a handheld mallet or a large wooden beam that is suspended by ropes. The thickness of the bell and being struck from the outside cause that deep resonating iconic sound that most people are familiar with when they think about Asian temples.

Bell Tower’s serve both practical and symbolic purposes within temples and monasteries as they are thought to have the power to 'awaken people from the daze of everyday life and the pursuit of worldly things like fame and fortune'. The ringing of the bells, which can often be heard within several kilometres of the temple is a reminder to people of all walks of life to slow down and enjoy life.

Donghe Bell Tower (東和鐘樓)

In 1908 (民治41年) the Soto Zen Daihonzai Temple (曹洞宗大本山別院) was constructed in Taipei’s historic Dongmen District (東門町), now Zhongzheng District (中正區). The temple which was designed in Japanese Zen Buddhist style was a popular place of worship but was initially limited solely to serving Japanese nationals who likely would have been among the bureaucrats working in the capital’s governing district.

Due to the popular demand however the group who controlled the temple eventually constructed a separate hall in 1914 (大正5年) to accommodate locals. The newly constructed hall, known as the Guanyin Hall (觀音堂), was situated directly to the side of the original temple yet was constructed in a traditional Fujian-style (閩式) rather than one that would be identifiable as a Japanese Zen Temple.

There could be a few reasons for this, but given the time period it was likely meant to segregate the two groups of worshippers while offering an olive branch of sorts to help integrate locals.

In 1916 the group who ran the temple constructed a Junior High School (私立臺灣佛教中學) for boys on the temple grounds. Even though they originally only intended for the school to help educate the children of the temple worshippers, it grew quickly and in 1938 was forced to relocate to Shilin District (士林區) changing its name to the “Private Taipei Junior High” (私立臺北中). Today the school still exists and is known as Taipei Junior High School (臺北市私立泰北高級中學).

In 1930 (昭和5年) as the temple had expanded in size and more importantly in the amount of funds that it was taking it, it was decided that a traditional bell tower should be constructed to act as the entrance and welcoming area for the temple.

As mentioned above, bell towers are common on Japanese Buddhist temples in Taiwan, but for the first twenty years of this temples existence, it had done without one. The Bell Tower at the temple was constructed using the “Hakamagoshi” (褲腰) architectural style meaning that it was more than one story tall and was a walled structure. The bell was on the second floor which had a narrow set of stairs leading up to it.

The bell was the final piece that was added to the temple grounds making it complete in its design - Unfortunately today, the only remaining parts of the original temple grounds are the bell and Guanyin Hall, which is somewhat hidden away behind a wall.

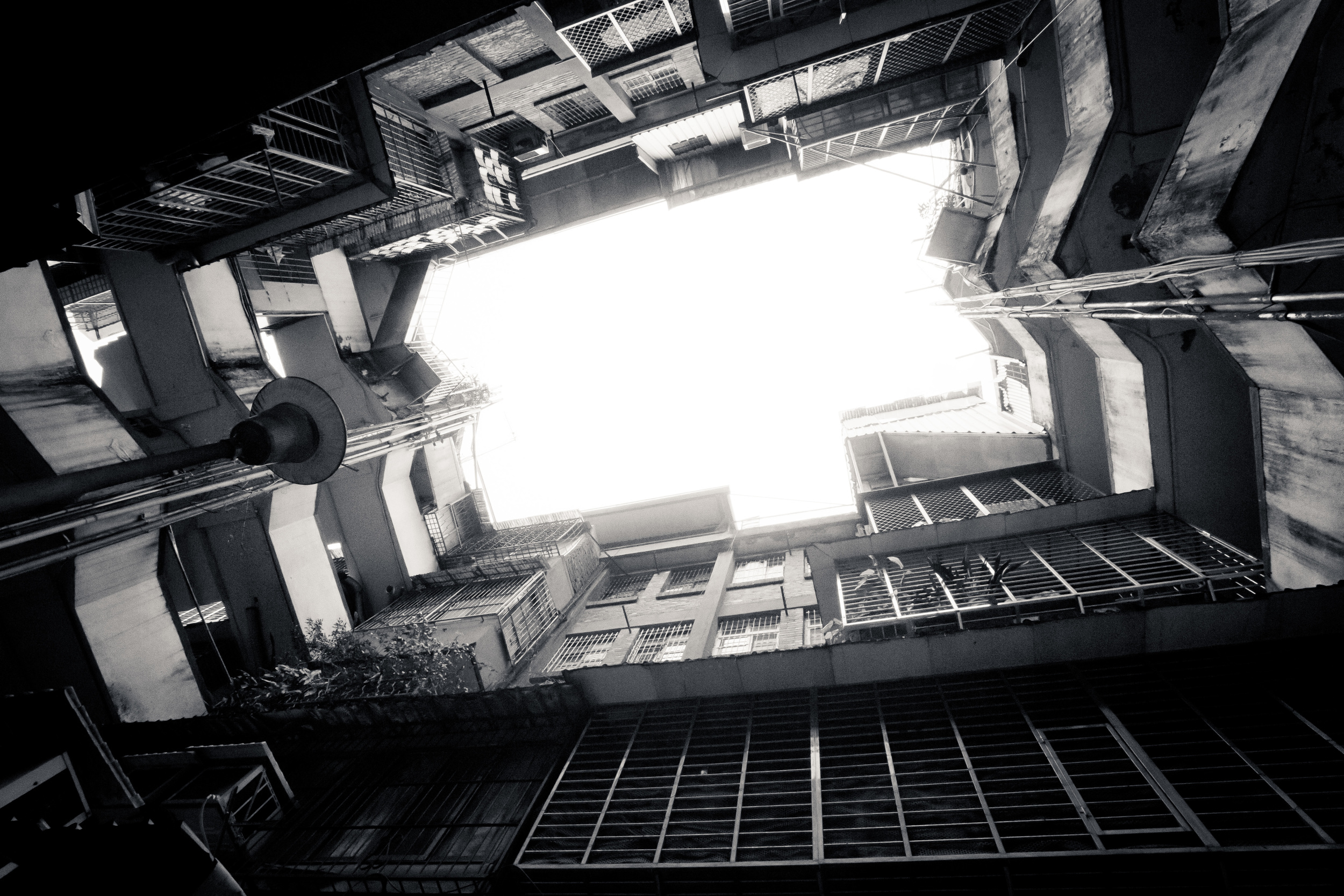

In 1945 when the Chinese Nationalists took control of Taiwan the temple grounds were taken control of by the government and for a period of time became home to a group of squatters who set up a shanty town on the grounds. Between 1945 and the year 2000 the beautifully constructed main hall was vandalized and left to decay by the government.

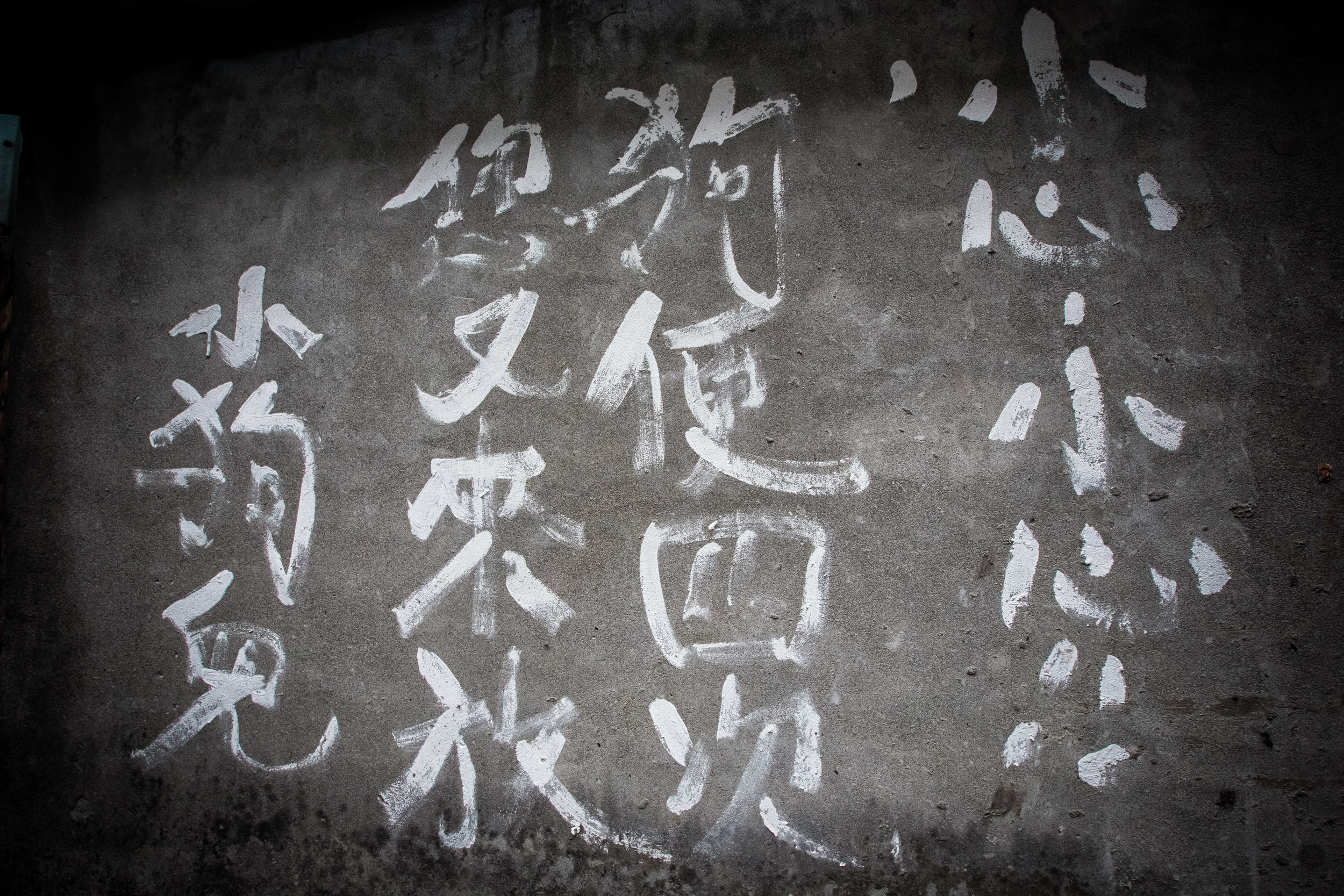

In the year 2000, the Taipei City Government made plans to relocate the squatters, tear down the shanty town and at the same time tear down the main hall and the bell tower. As I mentioned in my introduction, these plans met with resistance from local people who insisted that parts of the grounds be preserved. The government eventually capitulated and promised to both preserve and restore the historic Guanyin Hall as well as the Bell Tower with the project being completed in 2006.

While the Bell Tower stands as a beautiful reminder to the past, it is unfortunate that the original temple couldn’t have been preserved as well - the historic photos above show that it was a beautiful one and if it were still around it would serve as a great historic relic to the city as well as an important spot for tourists and local people to learn about the city’s history.

Taipei however is still home to two beautiful Japanese era Buddhist temples with the Puji Temple in Beitou and the Huguo Rinzai Temple next to Yuanshan MRT station and are always open to visitors.

Even though the original temple was demolished years ago, the Bell Tower remains an attractive tourist spot in a part of Taipei where not many tourists really spend a whole lot of time. If you are visiting the Chiang Kai-Shek Memorial Hall, you may want to consider taking the short walk to visit the beautiful bell tower. You really don’t need a lot of time to see it, but its an important historic site with a cute little Buddhist monastery to the rear.

Getting there

There are two different walking routes that tourists can take to arrive at the Bell Tower - Both routes are short walks from an MRT station, so its up to you which you prefer to take. The first route is a walk from the NTU Hospital MRT Station (台大醫院站) while the other is from the Chiang Kai-Shek Memorial Hall Station (中正紀念堂站).

The route from the NTU Hospital Station is a simple one - From the exit walk up Gongyuan Road (公園路) until you reach Ketagalan Road. Once you see the Xiananmen Rotary you just keep walking straight onto Ren’ai Road (仁愛路) until you reach Linsen Road (林森路) where you make a left turn. The Bell Tower is a block away from there.

The route from CKS Memorial Hall is a bit easier. Basically you just have to leave the MRT station and walk along Zhongshan South Road (中山南路) until you turn right on either Xinyi Road (信義路) or Ren’Ai Road (仁愛路) and then finally making a left turn on Linsen Road (林森路).

If I were a tourist, I would likely choose to first check out the CKS Memorial Hall and then when I was done, take the short walk from there to see the Bell Tower before moving on to check out the Presidential Building later in the afternoon. On the other hand if you decided to take the walk from NTU Hospital, you could also check out the beautiful 228 Peace Park (二二八和平公園) before moving on to the Bell Tower.

Gallery / Flickr (High Res Photos)