When it comes to my personal time, it’s rare that I ever find myself with nothing to do. Over the years I’ve curated a long list of places to go, things to do, and restaurants and coffee shops to check out. So, no matter where I find myself in Taiwan, I’m never far from somewhere I want to visit.

Something I’ve had to learn the hard way however, is that it is important to confirm that the places I’d like to visit are actually open to the public prior to leaving home. On far too many occasions, I’ve shown up only to find a locked door resulting in disappointment. To solve that from happening, I’ve had to further organize my list based on various factors and variables that most people would likely consider far too obsessive.

At the top of my list, you’ll find some of the nation’s most elusive destinations, and are those that are essentially only open to the public on special occasions - Places such as the Presidential Palace and other historic Japanese-era buildings in Taipei for example, which are currently home to important government offices, are some of the most difficult to check out, and if and when they’re open to the public, advance notice is often required for a permit for my camera gear. That being said, even though it seems like a hassle, when I’m able to check one of these destinations off my list, I rarely ever find myself disappointed.

So, when the opportunity presented itself to make a long-awaited visit to the ‘Taipei Guest House’, I woke up bright and early, hopped on a bus to Taipei, and spent a half day enjoying the absolute beauty of one of Taiwan’s most important heritage sites. Having been at the top of my list for what seemed like years, it’s one of those buildings that is only ever open to the public on special occasions, and unfortunately for me, when it is open, I’m usually stuck at work. That being said, there are (arguably) very few historic buildings in Taiwan that are able to compare to the spectacular architectural beauty of the Guest House, so with the rare opportunity to visit, I made sure to make the most of my time and also made sure to get all of the photos that I needed as I wouldn’t be able to visit again for quite some time.

Given how difficult it is to visit, I probably shouldn’t have been all that surprised to discover that there are very few authoritative resources available regarding the building and it’s history. So when I started the research portion of writing this article, there wasn’t a whole lot to rely on, save for an unusually detailed Wikipedia entry, and the typical information provided by the Ministry of Culture, which maintains open-source documents on most of the nation’s heritage sites.

Most of my go-to resources for the research I do weren’t offering much assistance, so this one required a trip to Taipei to the National Archives for some additional research as well as a trip to the library of Chung Yuan University (中原大學) to check out the work of one of the university’s professors, who has written extensively on the subject. I’m not really complaining though, visiting the archives is one of my favorite things to do as it is a treasure trove of invaluable information.

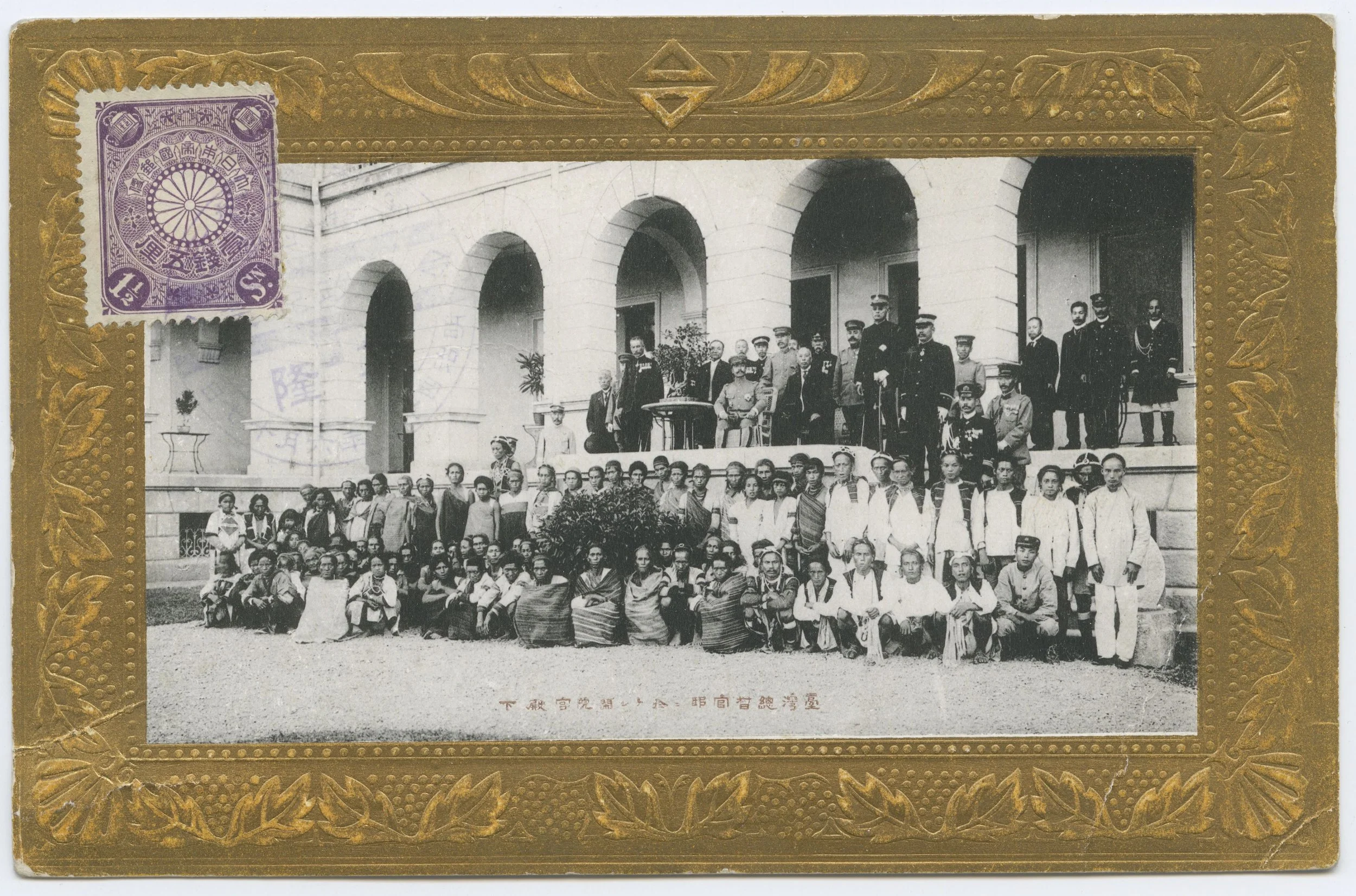

The Taipei Guest House, which was originally the Governor General of Taiwan’s official mansion, has played an important role throughout history - hosting important dignitaries such as members of the Japanese royal family, in addition to hosting diplomatic receptions and ceremonies for foreign dignitaries. So, for a building of such historic significance, I’m going to attempt to do my best to tell its story, properly and I hope that the photos I took during my visit do it justice.

I’ll start out by detailing the history of the Governor General’s Mansion and it’s architectural design, then move onto it’s post-war role as the Taipei Guest House, and end by offering information about how you can visit as well. By the end, I hope that if didn’t die of boredom reading the article that you’ll be inspired as inspired as I was to visit, when the building is open!

Taiwan Governor General’s Mansion (臺灣總督官邸)

By 1899 (明治29年), four years into Japan’s occupation of Taiwan, the colonial government had initiated a significant number of urban development projects around the island, hoping to be able to more efficiently bring the island under its control, as well as extracting its rich natural resources. The development projects included public works, a railway, civic buildings, and the reshaping of the towns and villages that would make up Taiwan’s future cities. In the capital, Taihoku, the government had been busy tearing down the Qing-era City Walls, and pretty much anything that stood in the way to make way for the ‘Chokushi Kaido’ (勅使街道 / ちょくしかいどう), otherwise known as the Imperial Road. That road, which is known as Zhongshan North Road (中山北路) today, essentially started in the location where the Governor General’s Mansion was planned to be constructed and went all the way to where the Taiwan Grand Shrine (臺灣神宮 / たいわんじんぐう) would be constructed, all for the purpose of allowing anyone visiting from the royal family to take a direct route from where they were staying to the shrine.

With the construction on the shrine and the mansion meant to start and completed at the same time, the thought was that these two symbols were meant to put Japan’s ‘power’ and ‘modernity’ on display, helping to convince the people of Taiwan that they were better off under the stewardship of the empire. The Governor at the time, General Kodama Gentaro (兒玉源太郎 / こだま げんたろう), who is remembered fondly for his eight year tenure contributing to the improvement of Taiwan’s infrastructure and the general living conditions, argued that the mansion was meant to symbolize the power of the emperor, and that no expense should be spared to ensure that it would be as imposing as it was beautiful.

Financed directly by the Japanese treasury, the high cost of constructing the mansion became a contentious issue back in Tokyo, especially given that some of the funds allocated for the Grand Shrine were being used for the mansion. Thus, Governor General Kodama’s right hand man, Gotō Shinpei (後藤新平 / ごとうしんぺい), who was the head of Taiwan’s Civil Affairs Office (台灣民政長官) at the time, was recalled back to Tokyo to explain personally to the Japanese government.

While the grilling he received from the Imperial Diet probably wasn’t his idea of a good time, Goto reiterated that the mansion represented the authority of the emperor in Taiwan, and given that few Taiwanese understood Japan’s power and prosperity, the stateliness of the mansion would help to convince them that they were part of something much larger and prosperous than they could have imagined.

Designed by architects Togo Fukuda (福田東吾 / ふくだとうご) and Ichiro Nomura (野村一郎 / .のむら いちろう), who are also credited with quite a few other buildings in Taiwan, the Governor General’s Mansion was completed on Sept. 26, 1901 (明治31年), at a total cost of 217,000 Yen, which is about the equivalent of $2.2 million US dollars today.

Note: Calculating Meiji-era Japanese currency against today’s standards is somewhat of a difficult process given that most records only date back to the restructuring of the Japanese economy, and massive inflation during the post-war period. To calculate the number above, I used the following formula: In 1901, the corporate goods price index was 0.469 where it is currently 698.6, meaning that one yen then is worth 1490 yen now. (217,000 x 1490 = 323,330,000) 昔の「1円」は今のいくら?1円から見る貨幣価値‧今昔物語

As mentioned above, the completion of the mansion was meant to coincide with the consecration of the Taiwan Grand Shrine, with the timing of the completion of both projects important given that ceremonies were planned to be held on the sixth anniversary of Prince Kitashirakawa Yoshihisa’s (北白川宮能久親王) death. Passing away during the conquest of Taiwan in 1895, the prince was enshrined within the Grand Shrine as “Kitashirakawa no Miya Yoshihisa-shinnō no Mikoto”, and his widow Tomiko (島津富子) traveled to Taiwan to take part in the ceremony, officially becoming the first member of the royal family to stay in the mansion.

Link: Taiwan Grand Shrine | 臺灣神宮 (Wiki)

Nevertheless, despite the amount of money that was used to construct the mansion, it was built at a time when the Japanese were yet to fully appreciate the awesome power of Taiwan’s termites, so after about a decade, the building had started to show signs of structural instability - This posed a considerable problem for the colonial government as it was not only used as the official residence of the Governor General, but also as his office. Similarly, it was thought that the mansion wasn’t actually designed to accommodate royal visitors, who often traveled with large entourages, which meant that a restoration and expansion project would have to take place to solve these issues.

In 1911 (明治44年), Governor General Sakuma Samata (佐久間左馬太 / さくま さまた), who is credited with introducing baseball to Taiwan a year prior, ordered the restoration and expansion of the mansion and enlisted a superstar architect, Moriyama Matsunosuke (森山松之助 / もりやま まつのすけ) to head up the project. With a budget of 150,000 Yen (approximately $1.5 million USD). The restoration process took two years to complete, and during that time, the Governor General and his family were moved to a temporary residence nearby.

Moriyama converted the exterior of the building from its original neo-renaissance style (新文藝復興樣式) design to a baroque design (新巴洛克形式), and converted the roof into a French-style Mansard design. Likewise, the interior space of the building expanded considerably and no expense was spared with regard to the mansion’s interior design; Imitating French palace design with Victorian floor tiles, fireplaces imported from Europe, rugs, sulk curtains, chandeliers, ornate stucco sculptures and decorations throughout the building.

In terms of the expansion, a total of 978㎡ (296坪) was added to the interior on the second and third floors, 333㎡ (101坪) for the balconies that surrounded the building, 36㎡ (11坪) for the porte-cochère (covered car port at the front of the building), and 19㎡ (6坪) for the dining room.

From 1901 until 1945, the Governor General’s Mansion housed sixteen of the nineteen Governor Generals who ruled over Taiwan during the Japanese-era. While no expense was spared in its renovations, a few short years after the project was completed, Moriyama Matsunosuke’s magnum opus, the iconic Government-General of Taiwan (臺灣總督府廳舍) building, known today as the Presidential Office (總統府), was completed and official government activities shifted from the residence to the massive new building a short distance away.

Link: Governor-General of Taiwan | 臺灣總督 (Wiki)

Nevertheless, the mansion continued to serve a dual-role as an official residence as well as receiving important guests and dignitaries, hosting members of the royal family, and was the ideal location for important government events - the most important of which came in 1923 (大正12年) when it hosted Crown Prince Hirohito (裕仁 / ひろひと) during his tour of Taiwan - just two years prior to ascending the throne as Emperor Showa (昭和天皇).

In 1945 (昭和20年), when the Second World War came to an end, the Japanese empire was forced to relinquish control of Taiwan as per the terms of their surrender. Leaving the island in a far better condition than they found it five decades earlier, the Republic of China took over and the Governor General’s Mansion became the official residence of the Provincial Governor of Taiwan (臺灣省主席). Then, in 1949 (民國38年), when the Chinese Nationalists were forced to retreat to Taiwan, after suffering devastating losses in the Chinese Civil War (國共內戰), they brought with them almost two million refugees, and the situation on the island changed completely.

Renamed the Taipei Guest House (臺北賓館) in 1950 (民國39年), the residence was put under the control of the Presidential Office, although it wasn’t used as one of the dozens of homes that President Chiang Kai-Shek (蔣介石) frequented during the remainder of his life in Taiwan. In 1952, in what could be interpreted as rubbing salt in their wounds, the Sino-Japanese Peace Treaty (中日和平條約), more commonly known as the Treaty of Taipei (台北和約) was signed at the Guest House, which was one of the iconic images of Japanese power in Taiwan, now under the control of the Chinese Nationalists. From then on, the Guest House has been used frequently for affairs of state, and has played host to foreign dignitaries and allies of the Republic of China, who are wined and dined in the historic building.

The building has been restored on two occasions in the post-war era, once in 1977 (民國66年) when the interior was refurbished and then again from 2002 to 2006 (民國90年-95年) after a powerful typhoon made landfall in Taiwan, causing considerable damage. Once the restoration of the building was completed, costing the government an astounding NT$400,000,000 ($13.5 million USD), the Guest House continued in its capacity serving as a venue for hosting state functions, but for the first time in more than a century, it was made available on select occasions for tours, allowing the general public to get a glimpse of the interior for the first time.

Governor General’s Mansion Timeline

1895 - Control of Taiwan is ceded to the Japanese at the end of the First Sino-Japanese war (淸日戰爭).

1895 (明治28年) - A temporary Governor General’s Office is set up within the Qing Dynasty’s Provincial Administration Hall (臺灣布政使司衙門), prior to moving to the ‘Western Learning Hall’ (西學堂), a school constructed by the Qing to study western civilization.

1900 (明治30年) - The first major urban development plan of the Japanese-era is completed for Taipei, and plans are drawn up to simultaneously construct a stately Governor General’s Mansion and the Taiwan Grand Shrine (臺灣神宮 / たいわんじんぐう).

1901 (明治31年) - Construction on the mansion is completed on Sept. 26, and the first person to stay inside was the widow of Prince Kitashirakawa Yoshihisa (北白川宮能久親王), who came to Taiwan to inaugurate the Grand Shrine on the sixth anniversary of her husband’s death.

1911 (明治44年) - Having suffered an incredible amount of structural damage caused by termites, the mansion undergoes a period of expansion and restoration, with famed architect Matsunosuke Moriyama (森山松之助) overseeing the project and resulting in the design of the building that we can enjoy today.

1913 (大正2年) - The restoration and expansion project on the mansion is completed.

1920 (大正9年) - Governmental affairs shifts from offices in the official residence to the newly constructed Government-General of Taiwan (臺灣總督府廳舍 / たいわんそうとくふ), currently the Presidential Office Building (總統府).

1923 (大正12年) - The mansion hosts Crown Prince Hirohito (裕仁 / ひろひと) during his tour of Taiwan, prior to his ascension to the throne as the Showa Emperor (昭和天皇) two years later.

1945 (昭和20年) - The Second World War comes to a conclusion with the formal surrender of the Japanese Empire and control of Taiwan is ambiguously awarded to the Republic of China.

1945 (民國34年) - The mansion becomes home to the Provincial Governor of Taiwan (臺灣省主席) for a short period of time.

1949 (民國38年) - Facing defeat in the Chinese Civil War (國共內戰), a massive retreat is ordered by the Kuomintang, and millions of Chinese refugees are brought to Taiwan.

1950 (民國39年) - The mansion is turned over to the Presidential Office (總統府) and is officially converted into the Taipei Guest House (臺北賓館).

1952 (民國41年) - The Treaty of Taipei (台北和約) is signed by representatives of the post-war Japanese Government and the Republic of China, formally ending the hostilities of the Second World War.

1963 (民國52年) - The Guest House is formally lent to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to facilitate the entertainment of foreign guests and dignitaries visiting Taiwan at state functions.

1977 (民國66年) - The interior of the building is restored by the government.

1998 - The Taipei Guest House is designated as a National Monument (國定古蹟), one of the highest levels of recognition awarded to heritage buildings under the current government system.

2001 (民國90年) - A considerable amount of structural damage to the building, likely as a result of Typhoon Toraji (颱風桃芝), forces the Ministry of Foreign Affairs to shut the building down.

2002 - 2006 (民國91年-95年) - The Taipei Guest House enters a four year long period of restoration that costs about NT$400,000,000 ($13.5 million USD).

2006 (民國91年) - After more than a century, the Taipei Guest House is opened up for the enjoyment of the public, however, only on very select occasions as it continues to serve as the venue for hosting state functions.

Now that I’ve gone through the history of the building, I’m going to spend some time describing it’s architectural design, which is quite significant given the age and importance of the building.

First though, as a show of respect for one of my favorite local writers, Han Cheung’s article about the mansion in the Taipei Times is probably one of the best English-language articles about the building that you’ll find, so I recommend giving it a read at some point.

Link: Taiwan in Time: An extravagant colonial palace (Han Cheung / Taipei Times)

Architectural Design

The architectural design of the building is a tale that is told in two different chapters, namely the extravagant ‘first generation’ design, and the ostentatious ‘second generation’ design, which built upon what came before it. Touching on its designers earlier, it’s important to repeat that the mansion, completed in 1901, was the brainchild of Togo Fukuda and Ichiro Nomura, a pair of accomplished architects who designed a fair number of the earlier buildings constructed during the Japanese-era. Building upon his predecessors work, Moriyama Matsunosuke, a man who I personally consider one of Taiwanese history’s most prolific architects, swooped in and made the sweeping changes to the building’s design, which also helped to ensure its longevity, and is one of the reasons why we’re able to continue enjoying it today.

Note: I’m pretty sure that not everyone pays as much attention to these things as I do, but if we take a look at the work of Moriyama, many of the iconic buildings he designed are still standing and in operation today, including the Taichung Prefectural Hall (台中州廳), the Monopoly Bureau (専売局), the Taipei Prefectural Hall (台北州廳), Tainan Prefectural Hall (台南州廳), the Taipei Railway Bureau (台北鐵道部), the Taipei Aqueduct (臺北水道水源地) and the Presidential Office (總統府).

First Generation Governor-General’s Mansion (第一代總督官邸)

As previously mentioned, there are some very noticeable differences in the design of the first generation mansion, and what came later. In both cases however, the architects sought to mimic the architectural design that was popular in Europe at the time. The first generation mansion designed by Togo Fukuda and Ichiro Nomura adhered to the ‘Neo-Renaissance’ style of design popularized in France and inspired by Italian architects. The end result was a building characterized by its rectangular and circular decorative elements on the exterior of the building. Staying true to the revival-style design, the building featured a rectangular main-wing in the center with asymmetrical wings on both the left and right. It also adhered to what is known as ‘flat classicism’ in that the exterior walls feature very few decorative elements, placing greater importance on proportion, harmony, and linear symmetry.

One of the questionable aspects of the ‘asymmetry’ of the wings however. was that the original western wing was a flat square section that prominently featured a dome, one of the important aspects of European architectural design that made a comeback with the revival style. The eastern-wing meanwhile was concave in design, and instead of a dome, featured a roof-covered balcony, with an almost 360 degree view of the area surrounding the mansion.

The two-story residence was constructed using a mixture of brick and stone with wooden roof trusses in the ceiling, helping to keep the roof in place. Surrounded on all sides by covered verandas, the one area where you’d find curved arched spaces in the design.

The usage of the interior space was unlike what you’d expect from a traditional Japanese-style mansion in that only the east-wing of the second floor was reserved as the private residence of the Governor-General and his family, while the first floor was home to a reception lobby, administration office, meeting rooms, a banquet hall, and a game room.

Where much of the beauty of the original design came into focus was within the interior where there was beautifully laid parquet flooring and stucco columns located throughout the building that played both functional and decorative roles. Given that the mansion was meant to imitate that of a European palace, the interior also featured beautiful chandeliers, silk curtains, and many other imported decorative elements.

Finally, one of the lasting design elements of the building were the gardens that surrounded the building, featuring European-style gardens in the front and a Japanese-style garden to the rear.

Unfortunately, almost all of the remaining photos of the first generation mansion were taken of the exterior, so describing the beauty of the interior design is something that can only be done through the interpretation of historic records.

Second Generation Governor-General’s Mansion (第二代總督官邸)

In what one could assume was simply a natural progression from the Renaissance-Revival architectural style of the first generation version of the mansion, architect Moriyama Matsunosuke completely redesigned the mansion into a style more commonly associated with what is known as either Neo-Baroque, or Baroque-Revival, a style which would become quite prominent in both Taiwan and Japan in the early 20th century.

Possibly taking inspiration from Tokyo’s Akasaka Palace (迎賓館赤坂離宮 / げいひんかんあかさかりきゅう), one of the Japanese government’s two current official state guest houses, Moriyama’s alterations to the building were decorative in nature, but also practical in that his work ensured the longevity of the building’s structural health. The project got underway in 1911 when then Governor General Sakuma Samata ordered the restoration and expansion of the mansion, and during the two years that it took to complete, the Governor-General and his office vacated the residence.

Moriyama’s vision threw out all of the straight lines and the ‘flatness’ of the original and replaced them with curvaceousness and an array of rich surface treatments carved into the facade of the building. The most noticeable differences can be found in the center of the main wing of the building where Moriyama completely redesigned the roof, windows and the second-floor balcony. Most notably, within the triangular section between the upper part of the balcony and the third floor, the once empty section features some pretty important carvings. Displaying the official logo used during the Japanese-era to signify Taiwan, an important part of the stamp that signified the office of the Governor-General. Likewise, in all of the flat empty sections of space above and below the windows, decorative elements were added to show off the ‘flowing nature’ of baroque architectural design.

Given that Taiwan’s termites were having a wonderful time with the wood used to construct the building, having learned their lesson the hard way, Japanese architects came up with methods to solve these problems. In this case, Moriyama replaced the original wooden roof trusses in the building with steel trusses and converted the roof into a two-sloped Mansard-style design, a style common among the architecture of French palaces. In this case, the roof allowed for circular dormer windows (ox-eye 牛眼窗), a favorite of Japanese architects at the time, but more importantly, these changes allowed for the construction of a third floor, increase in the interior space of the building.

Link: Mansard Roof (Wiki)

With 978㎡ (296坪) of floor space added to the mansion during the expansion, design of the interior space likewise required a considerable amount of attention, and with a budget that was nearly half of the original cost of construction, no expense was spared. When the project was completed, the mansion would have appeared similar to what you’d expect from a typical French palace. Featuring stucco sculptures, columns, stained glass windows and beautiful white walls mixed featuring golden mosaics and carvings throughout the interior.

I’m not exaggerating when I say that my experience walking through the mansion was similar to walking through parts of the Vatican. I felt like I was transported back to my travels through Europe, which isn’t a feeling you often get while visiting historic buildings in Taiwan. I suppose that shouldn’t be particularly surprising though, given that these decorative elements are all indicative of Baroque design. Exploring the second floor, especially, it should be quite easy to see why with all of the flowing golden arches and the network of pillars that you’ll see in each of the rooms open for the tour.

Another important aspect of the restoration project that should be mentioned was to add a bit of modern technology was added to the building, included retrofitting for modern lighting and central heating systems. I’m not particularly sure why a heating system was necessary given Taiwan’s climate, but in addition to central heating, seventeen fireplaces were imported from Europe along with rugs, silk curtains, chandeliers and Victorian floor tiles to complete the redesign.

Having experienced and enjoyed Moriyama’s work in a few of Taiwan’s other historic Japanese-era buildings, it’s easy to see why he was chosen to be the designer of so many of the colonial government’s most important construction projects. The legacy that he’s left here in Taiwan is one that we’re fortunately able to continue enjoying more than a century after he hopped on a boat and headed back to Japan.

Link: The helmsman who shaped the style of Taipei City (Shelley Shan / Taipei Times)

Interestingly, despite his love of European Baroque revivalist design, when Moriyama returned to Japan in 1921, he took on an assignment designing the ‘Imperial Pavilion’ at Shinjuku Gyo-en National Garden (新宿御苑 / しんじゅくぎょえん), dedicated to the Showa Emperor. The pavilion, which is now regarded as the “Taiwan Pavilion” was constructed using Taiwanese cypress and traditional red clay bricks, took inspiration from traditional Taiwanese architectural design, an obvious nod to his years here.

Visiting the Taipei Guest House (臺北賓館)

After more than a century, tours of the Taipei Guest House opened to the public in 2006, just after the building had finished being restored. Having entered an era of democratic openness and transparency, I imagine it’s only understandable that the government couldn’t very well justify spending so much money restoring a building that so few of the nation’s taxpayers would ever be able to enjoy.

Starting from June 4th, 2006, the Guest House was set to be open to the public on the first Sunday of even months, essentially making it available to the public six days a year. However, over the decade since tours started, the number of days that the building is available has slightly increased, but the availability of these tours depends on the annual schedule of events taking place within the building.

So, even though it is supposed to be open on certain weekends, depending on whether or not any state functions are taking place, you might end up being a little disappointed if you try to visit without checking beforehand.

Suffice to say, with Taiwan closing its borders during the COVID-19 pandemic, the building was open for tours more often than in previous years, but there is no indication as to whether or not this will become the norm in years to come as the world opens back up for tourism. Additionally, given the number of international policy makers finding their way to Taiwan as of late, it’s only understandable that the number of official events taking place at the mansion will increase, which means that the number of public tours will decline.

If you would like to visit the Guest House, it’s important that you pay close attention to the yearly calendar of openings on the Ministry of Foreign Affairs official website, which is linked below:

Link: Open House Schedule | 假日開放參觀

I caution you however that Taiwanese Government Websites are notorious for randomly disappearing, so if either of the links provided above aren’t working, I recommend heading over to Google and typing “Taipei Guest House” or “台北賓館” where you’ll likely find whatever new website they’ve started using in addition to the schedule of open houses for the year.

A tip that you may find helpful is that whenever the Guest House is officially open for public tours, the Presidential Office is as well, so if you’re feeling ambitious, you might be able to enjoy a tour of both buildings on the same day, although for someone like me, I’d find it far too difficult.

While touring the building, you’ll be able to walk around the open areas freely, but there are quite a few sections of the building, and the gardens, which are off-limits to guests. You’ll notice that there are volunteers watching at all times to make sure you don’t stray off into an area where you’re not welcome. Similarly, if you’re carrying a lot of photo gear, it’s important to remember that flash photography is prohibited within the building, and you’re also not permitted to use a tripod.

Interestingly, if you break any of the guidelines set for visits, it’s likely that you’ll be asked to leave immediately, which will also result in a two year ban - So try to be on your best behavior!

Getting There

Address: (臺北市中正區凱達格蘭大道1號)

GPS: 25.039810, 121.515870

Located within the heart of the governing district of the capital, the Taipei Guest House is situated a short distance from the Presidential Office (總統府), the Chiang Kai-Shek Memorial Hall (中正紀念堂), the East Gate (景福門) and the 228 Peace Memorial Park (二二八和平公園). Similarly, it is within walking distance of several of Taipei’s MRT stations, so getting there should be relatively straight forward.

While the Guest House is located closest to the NTU Hospital MRT Station (台大醫院捷運站), you could also elect to walk a short distance from either Taipei Main Station (台北車站), Ximen Station (西門捷運站) or Chiang Kai-Shek Memorial Hall Station (中正紀念堂捷運站). For most people however, the chance to visit the Guest House is one of those things where you won’t want to waste too much time on a walking tour of the capital, so your best option is to make your way directly to the NTU Hospital station and take either Exit 1 or Exit 2 where you’ll walk a short distance along Gongyuan Road (公園路) to the front gate on the corner of Gongyuan and Ketagalen Boulevard (凱達格蘭大道).

Bus

As far as I’m concerned, the MRT is probably your best method of getting to the Guest House, but there are quite a few people who swear by Taipei’s excellent public bus system, so if you’re one of them, you’re in luck as you are afforded a number of options in this respect given that it is located next to one of the city’s most important hospitals. You’ll find that there are a number of bus stops within walking distance, but I’m only going to provide the bus routes for the closest bus stop to save both myself and yourself some time.

NTU Hospital MRT Station Bus Stop (捷運台大醫院站): 2, 5, 18, 20, 37, 222, 241, 243, 245, 249, 251, 295, 513, 604, 621, 640, 644, 648, 651, 656, 670, 706, 835, 938 East 0, 信義幹線, 仁愛幹線

Click on any of the links above for the route map and real-time information for each of the buses. If you haven’t already, I recommend using the Taipei eBus website or downloading the “台北等公車” app to your phone, which will help you map out your trip.

Youbike

If you’ve decided to ride one of the city’s popular Youbike’s to the Guest House, you’re in luck as there are Youbike docking stations located near the NTU Hospital MRT Station exit, where you can dock your bike and then walk over to the Guest House. You can also find additional docking stations on either side of the East Gate as well as along the entrance to Chiang Kai-Shek Memorial Hall.

If you haven’t already, I highly recommend downloading the Youbike App to your phone so that you’ll have a better idea of the location where you’ll be able to find the closest docking station.

The Taipei Guest House has hosted princes and princesses to presidents, prime ministers, etc. - As one of Taipei’s most important destinations for state functions, the stately mansion has played host to countless events over the past one hundred and twenty years, and will continue to serve an important role for marketing Taiwan to the rest of the world.

Now that we, the little people, are able to enjoy a taste of the Guest House, it’s become a pretty popular tourist destination, especially for domestic tourists. If you’re in Taiwan and you have the chance to visit, you should probably take the opportunity to enjoy a tour. It’s highly recommend however that anyone wanting to visit pay close attention to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs website (linked above), which provides the list of dates on the annual visitation schedule, so that you don’t miss out.

References

Taipei Guest House | 台北賓館 (Wiki)

Taipei Guest House | 台北賓館 (Ministry of Foreign Affairs / 外交部)

Taipei Guest House (Digital Taiwan)

臺北賓館 (國家文化資產網)

台北賓館:不曾被遺忘的華麗建築 (公共電視台 異人的足跡)

國定古蹟台北賓館調查研究/原台灣總督官邸 (黃俊銘)

Taiwan in Time: An extravagant colonial palace (Han Cheung / Taipei Times)

Lafayette East Asia Image Collection (Historic Photos)