How much do you know about Okinawa? If you’re like most people, you probably learned in history books that it was the location of one of the most devastating battles of the Second World War. That unfortunately might be the extent of your knowledge about this small, yet extremely beautiful archipelago of islands known as the Ryukyus.

What happened before the war? What happened after the war?

These are questions that anyone planning a visit should be asking.

Okinawa’s history is an extremely complex one and if you’re not well-versed, don’t worry, if you visit, you’re going to get a crash course.

The Okinawa of today has developed into a modern, yet beautiful tropical island with excellent infrastructure and public transportation that provides easy access to all the other outlying islands and amazing beaches.

Its hard to fathom while walking down the clean, well-organized streets that half a century ago, the entirety of the island was reduced to a festering pile of rubble and human misery.

In the aftermath of the war, Okinawa redeveloped at an amazing pace, but while homes and businesses can be rebuilt, something that the people of Okinawa continue to struggle with today is that they’ve lost so much of their culture, language and identity through all of the chaos..

This is something that the people of Okinawa have worked tirelessly at rectifying over the past few decades and now the fruits of their labor are taking shape as there has been a cultural revival of sorts when it comes to the local language, culture and customs, which the local people have become so very proud of.

What this revival also shows quite clearly is that there is a stark contrast between the Ryukyuan people and their Japanese compatriots and that while they might have a shared history, they’re not one in the same.

Link: Battle of Okinawa’s legacy lives on 70 years later as locals chase against Japanese rule, US arms (The Conversation)

In the aftermath of the war, reconstruction efforts focused primarily on building modern infrastructure and homes for all of the people who were displaced. Suffice to say that many of the buildings of cultural or religious significance that were lost weren’t really high in priority.

This meant that the various Ryukyuan castles like Shuri Castle, Nakagusuku Castle and Zakimi Castle as well as various tombs and places or worship weren’t rebuilt.

The Eight Ryukyuan Shrines (琉球八社) for example, which were (for the most part) places of worship created for the Ryukyuan folk religion (and later converted into Shinto Shrines) were eventually rebuilt, but it would take until the 1990s (or later) Or for most of them to reappear in some shape or form.

Links: Ryukyu Eight Shrines 琉球八社 (Samurai Archives) | 琉球八社 (Wiki)

When reconstruction efforts on these shrines finally began, priority was given to the largest and most significant of them, namely, Futenma Shrine (普天滿宮) just outside of the capital. Next came Naminoue Shrine (波上宮), Okinawa’s “ichinomiya” (一宮), the highest-ranking shrine in the prefecture.

Naminoue Shrine, known simply to the locals as ‘Nanminsan’ has a long history dating back to at least the 1300s and today is the most widely-visited place of worship in all of Okinawa.

The shrine is not only one of the most important religious sites in the capital city, but is also a place of worship that is uniquely ‘Okinawan.’ Even though it maintains many of Japan’s traditional design elements, it is unmistakably something that you’re only going to see in Okinawa which makes it stand out from the 80,000 other shrines across the country.

Naminoue Shrine (波上宮)

Literally, the “Above the Waves Shrine”, Naminoue Shrine, pronounced [Na-mi-new-oh-eh], sits high on its perch above the Naha Harbour.

The internet is full of claims that the history of the shrine dates back almost a thousand years, but that is actually a bit misleading. There isn’t actually any recorded information or evidence that gives an exact date as to when a shrine was first constructed in this location.

What we do know about the origins of the shrine are from local legends. The story goes a little like this: A shrine was constructed by a fishermen who one day came across a mysterious stone and, (as one does), began to pray to it, which caused the stone to start glowing. Soon after the fisherman started taking in record hauls which eventually caught the attention of the local gods who stole the rock. From that time on though, an oracle took up residence in the area and people started visiting for spiritual guidance.

The first documented information about a shrine in the area comes from the “Ryukyu-Koku-Yurai-Ki” (琉球國由來記) or “the Record of Origin of the Kingdom of Ryukyu” which tells of a Buddhist Temple, the “Naminoue-san Gokoku-ji” (波上山護國寺), which was constructed in 1367 and would later burn to the ground in 1633.

The shrine would then return to its folk-religious roots and as its reputation for spiritual greatness spread throughout the land, it became habit for the sailors coming in and out of Naha harbour to look up and say a prayer for protection on their journey. Lending credence to the claims of Naminsan’s spiritual power, the Ryukyuan Kings also made a yearly ritual of visiting the area to formally pray on behalf of the nation for peace and prosperity.

Note: The local folk religion, known as “Nirai Kanai” (ニライカナイ信仰) or simply as “Ryukyuan Shinto” (琉球神道) is similar in a lot of ways to Japanese Shintoism. The religion honours the relationship between the living and the dead as well as the gods and spirits of the natural world, but is also predominately a medium of ancestral worship.

Nanminsan was dedicated to the local religion for hundreds of years, but that came to an end when the Japanese annexed the Ryukyuan Islands and formally put an end to the Ryukyuan Kingdom in 1879. From the outset, the Japanese treated the Ryukyuan people as second-class citizens and attempted to erase their culture and language. The local folk religion became one of the colonial powers first targets and Nanminsan being one of the most sacred spaces in the land was replaced by the “Naminoue Shinto Shrine” in 1890.

The newly established Naminoue Shinto Shrine was classified at the time as the “Okinawa Sochinju” (沖繩總鎮守社), which mean that it was dedicated to the “protection and tranquility” of the entire prefecture. The problem for the Japanese however was that the local people resisted, so they capitulated and enshrined several of the Ryukyuan Kings as gods at the shrine in an attempt to appease the locals.

This in turn also helped the Japanese integrate the royal family into the Japanese Imperial structure.

In 1923, the shrine was completely rebuilt and all of the traditional Okinawan design elements were replaced by traditional Japanese design. That version of the shrine however only lasted for a few decades though as it was completely destroyed during the Battle of Okinawa in 1945.

In the years following the war, the shrine was slowly rebuilt with initial construction focusing on the Shamusho (社務所) and Honden (本殿), which were completed in 1953. It would take another four decades to raise enough money to complete the rest of the shrine (which is something I think in retrospect that we can be thankful for) as the Haiden (拜殿) and several other parts of the complex were completed and opened to the public in 1993.

The reason why I suggest that we’re fortunate is because the completed structure that we see today is a beautiful fusion of Japanese and Okinawan traditional design that might not have been possible if it were completed sooner. The resurgence of the Ryukyuan cultural identity has fueled a need for local places of worship to better represent the local population, so the end result is a unique shrine that pays home age to the beautiful Ryukyuan islands.

Link: Naminoue Shrine (The Samurai Archives) | Origin of Naminoue Shrine (波上宮)

Kumano Worship (熊野三山)

Before we get into some of the different design elements of the shrine, I’d like to take a few minutes to explain Kumano Worship, which is something most people might find a bit a confusing about Okinawa’s Shinto Shrines. It is rare that you’ll find an article that touches on the subject, so I’ll try to explain it as best as I can, but it’s important to note that a lack of recorded history makes this stuff a little difficult to explain.

One of the common features of all of Okinawa’s Shinto Shrines is that they are dedicated to Kumano Worship - which is a Shinto tradition that hails from the mountainous Kumano (熊野) region that spans the prefectures of Wakayama (和歌山縣) and Mie (三重), about 100 kilometres south of Osaka (大阪) on Japan’s main island.

Kumano Worship might not attract as many followers as some of Japan’s other Shinto sects, but it is thought to predate all of Japan’s modern religions. Centered around the three UNESCO World Heritage Shinto Shrines: Hongu Taisha (本宮大社), Hayatama Taisha (速玉大社) and Nachi Taisha (那智大社) the area is considered to be a place of physical healing and is often mentioned in the mythology surrounding Japan’s founding.

Today there are more than three-thousand shrines throughout Japan dedicated to Kumano worship, each of which goes through a special propagation process known as “bunrei” (分霊) where the spiritual power of the Kumano deities are shared with a new shrine. Over the past thousand years as Kumano worship spread throughout Japan, followers including Emperors, Samurai and commoners alike have all been attracted to the area to take part in the Kumano Kodo (熊野古道), one of the worlds most important religious pilgrimages.

There are numerous legends that deal with the origin of Kumano Worship, which all deal with the power of nature. Not only is the Kumano area credited with being the mythological birthplace of Japan, it is also known as the “land of the dead” where various kami retire in death - including the gravesite of Izanami (伊邪那美), the deity who created the earth together with her husband Izanagi (伊邪那歧).

So how did Kumano Worship become such a big thing in Okinawa?

That is actually quite a difficult question to answer due to the lack of recorded history. What we do know is that the Ryukyu Kingdom was a major player in the East Asian trade networks and that they learned a lot from foreigners, especially those from China, Japan and Korea.

The influence these other nations had over the Ryukyus not only involved international trade but the sharing of technology, education, governance, religion, etc.

What little we know about Kumano’s arrival in the kingdom comes from the Ryūkyū Shintō-ki (琉球神道記), a book authored by a Buddhist monk that documented the Ryukyuan religious experience in the early 1600s. We also know that the Futenma Shinto Shrine (普天滿宮), which was established in the 14th Century was one of the first shrines in the Ryukyus dedicated to Kumano worship, so its likely that Kumano worship spread to Okinawa well before the kingdom was established.

In the book, monk Taichū Ryōtei (袋中良定) explains that the propagation of Kumano Worship in Okinawa was likely the result of traveling Buddhist monks who visited the islands. At that time, Buddhism and Shintoism were considered to be synchronized with each other, so it shouldn’t be surprising that Japanese monks spreading Buddhism also helped to spread Shinto beliefs as well.

In one story, Monk Nisshu (日秀), who is credited with the establishment of the Kin Kannon Temple (金武觀音寺), used his supernatural powers to save the local village from a rowdy bunch of venomous snakes and from there stayed in Okinawa to spread Buddhism and Kumano Worship.

Likewise there are several other stories of monks becoming shipwrecked or traveling specifically to Okinawa on exchange to spread Buddhism. None of these stories however fully explain why Kumano Worship in particular was so heavily promoted - It is safe to assume though that as Kumano was home to one of the more established Shinto sects in Japan as well being home to what many people considered to be the “Pure Land”, it was a major centre for Buddhist training which meant that many of the monks who later became missionaries would have trained in the area.

Link: 沖縄の熊野信仰霊場を訪ねて (Japanese)

Points of Interest

There are quite a few small details to take note of when you’re visiting this little shrine and each of them serves a very specific and important purpose. Below, I’ll introduce some of the most important points of interest at the shrine that you’ll want to pay attention to, but if you’d like a more detailed introduction to Shinto Shrines, their history and architecture, I recommend checking the link below to learn more about Japan’s traditional places of worship.

Link: Shinto Shrine: History, Architecture, and Functions (Patternz)

Shrine Gate (鳥居)

The gate to the shrine is known in Japan as a "Torii" gate, which simply translated into English as a ‘bird perch’. These gates are typically found at the entrance of a shrine and their purpose is to demarcate the transition from the outside profane realm to that of a sacred one. This means that once you pass through the gate, it is time to stop joking around and to be respectful.

The Torii at Naminoue Shrine is known as a Myojin Torii (明神鳥居) which is one of the most common styles in Japan and simply means that its upper beam is curved while the lower beam is straight. Between the two beams there is a plaque that reads “Naminoue Shrine” (波上宮) and on either side of the gate you’ll find two large stone lanterns that light up the gate beautifully at night.

The gate is the largest of its kind in Okinawa and not only is it quite tall, its also wide enough to allow a lane for cars to enter on one side with pedestrian traffic on the other.

Once you reach the top of the hill there is a second Torii gate that you have to pass through before reaching the interior section of the shrine. This gate is situated a level above the parking lot, so it allows people who have driven their cars into the shrine and parked their cars to also walk through a part of the visiting path to the shrine. This stone gate is much smaller than the first one and hung from the lower beam of the gate you’ll notice something known as the “sacred rope” or the “shimenawa” (標縄). The rope is thick and is decorated with “shide” (紙垂), which are beautifully cut paper streamers that are used in Shinto rituals. These sacred ropes are found all over Japan and have many different uses but here at the Shinto shrine it is used to help ward away evil spirits

Visiting Path (參道)

The “Sando” (參道) or “Visiting Path” is a common feature with Japanese Shinto and Buddhist places of worship and acts as a path that leads to the Hall of Worship. The length of the path varies between shrine with some being quite short while others are several kilometers long.

The path at Naminoue Shrine is a short one that winds up a small hill and consists simply of a set of cement stairs with stone lanterns on the left and a small barrier fence on the right. As I mentioned above, the path is split into two with pedestrian traffic on the right and a road for cars to reach the shrines small parking lot.

Once you’re at the top of the hill, you’ll pass through another Torii gate and the path to the main hall will come into view with the Purification Fountain on your left and the Administration Office on your right.

Purification Fountain (手水舍)

An important aspect of Shintoism is something known as the "sacred-profane dichotomy". In terms of this temple, the Torii gate at the entrance of a temple separates the world of the 'sin' from that of the 'sacred'. When you walk through the gate you are leaving the world of the profane which means that you should do so in the cleanest possible manner. So in order to ready yourself for entrance into the sacred realm you would have to do so with a purified body and mind.

As you approach the Purification Mountain or “chozuya”, you’ll notice a handy guide next to it that indicates the proper method of purifying yourself with a ceremony known as “temizu” (手水). The simple ceremony includes a few gestures that you’ll probably want to take part in if not just as a sign of respect, but because its hot in Okinawa and washing yourself with cold water is quite refreshing.

Pick up a ladle with your right hand, fill it with water and clean your left hand.

Swap the ladle to your left hand and then wash your right hand.

Swap hands again and pour some water into your left hand and take a drink.

Wash your left hand again and then tilt the ladle vertically so that the remaining water runs down the handle.

What I really like about the Purification Fountain at this shrine is that it is situated within a tree covered area that offers visitors some respite from the sun. The fountain itself is beautifully decorated with the water spouts appearing in the shapes of dragons and the fountain itself made of a dark black coloured stone.

Administration Office (社務所)

The “Shamusho” (社務所) is opposite the Purification Fountain and reaches as far as the Hall of Worship. The building is traditionally used to conduct the business of running the shrine and also acts as a place to allow the shrine personnel to rest.

It is also where you’ll go if the shrine is holding a lecture or if the priests are holding special events or prayer ceremonies that aren’t held in the Hall of Worship. You’re likely to notice a long line of visitors at a window at the building as this is where you’re able to purchase good luck charms, amulets, ema, etc. from the shrine.

In the case of this shrine though, I gather that most of these public events are likely held at the Shrine Association building (神宮會館) which is directly across the street from the main gate. While not officially within the shrine area, the association building is frequently used for large public events and weddings and is where you’ll want to go if you want to rent a traditional Japanese yukata to get photos of yourself for your shrine visit.

Stone Guardians (狛犬)

One of the common features that you’ll find in the many of the places of worship throughout East Asia is that the temples and shrines are usually guarded by stone lion-dogs known in Japan as “Komainu” (狛犬). Thought to have originated in Korea, they typically appear in front of a temple and are meant to help ward off evil spirits.

Okinawa being Okinawa though, the traditional stone lion-dogs that guard the shrine have been replaced with the local version, the Shisa (シーサー), or “Shi-Shi” (獅子) in the local Ryukyuan language. The Shisa lions, I guess you could say are a distant cousin of the Komainu and are prevalent throughout the Ryukyuan islands acting as not only the guardians of temples and shrines, but also homes and businesses as well.

The Shisa first appeared in Okinawa in the 15th Century and in the years since the lion has transformed into an image that symbolises the cultural identity of the people of the Ryukyuan islands and there are many legends in the area that tell of how they arrived.

Hall of Worship (拜殿)

Shinto Shrines are renowned for their impressive ability to blend in harmoniously with the natural environment around them, which shouldn’t really be all that surprising considering that it is a religion that worships deities related to nature.

If you weren’t already aware, the Shinto deities, or “kami” are almost always objects found in the natural environment such as animals, birds, rivers, mountains, trees, etc. For outsiders this can be a bit confusing, especially since there are eight million different kami - a number that is synonymous with infinity.

For the Shinto, the relationship with the natural environment is extremely important given that the earth can bring both blessing and disaster. It is thought that if the kami are worshipped adequately and in a responsible way, then they will bring good fortune to the world. If on the other hand they are disrespected or neglected, they will react violently or bring misfortune.

Essentially, respect for the environment is one of the main tenets of Shintoism and the construction of these shrines never fails to keep that in mind. With over 80,000 shrines in Japan, Shintoism contributes to society providing ecological sanctuaries that can be enjoyed by all.

The thing is though, the natural environment in Okinawa is considerably different than what you’ll come across in other parts of the Japan. This means that what you’re going to experience at Naminoue Shrine is going to be a lot different than what you’d see anywhere else in Japan. The shrine of course keeps with tradition and is surrounded by nature, but as it is situated atop a cliff that overlooks a pristine beach, the area around the shrine is covered with palm trees and tropical plants.

The design of the Hall of Worship, or the “Haiden” likewise is unique to Okinawa as it was constructed according to Japanese tradition but designed in a way that pays homage to the Ryukyuan people, especially with with its usage of the colour red and the beautiful red tiled “Aka-Gawara” (沖繩赤瓦) roof that has become synonymous with the architecture found all over Okinawa.

The combination of the three primary colour with the red on the shrine, the green palm trees and the beautiful blue Okinawan sky makes the shrine appealing to the eye and allows it to stand out in the sunlight.

Link: Ryukyuan Architecture in Zamami: Red Tile Roofs (The Zamami Times)

As you approach the Hall of Worship, the first thing that will stand out to you is the beautiful red roof and pillars mixed with the painted white walls. The closer you get though, the smaller details become much more apparent.

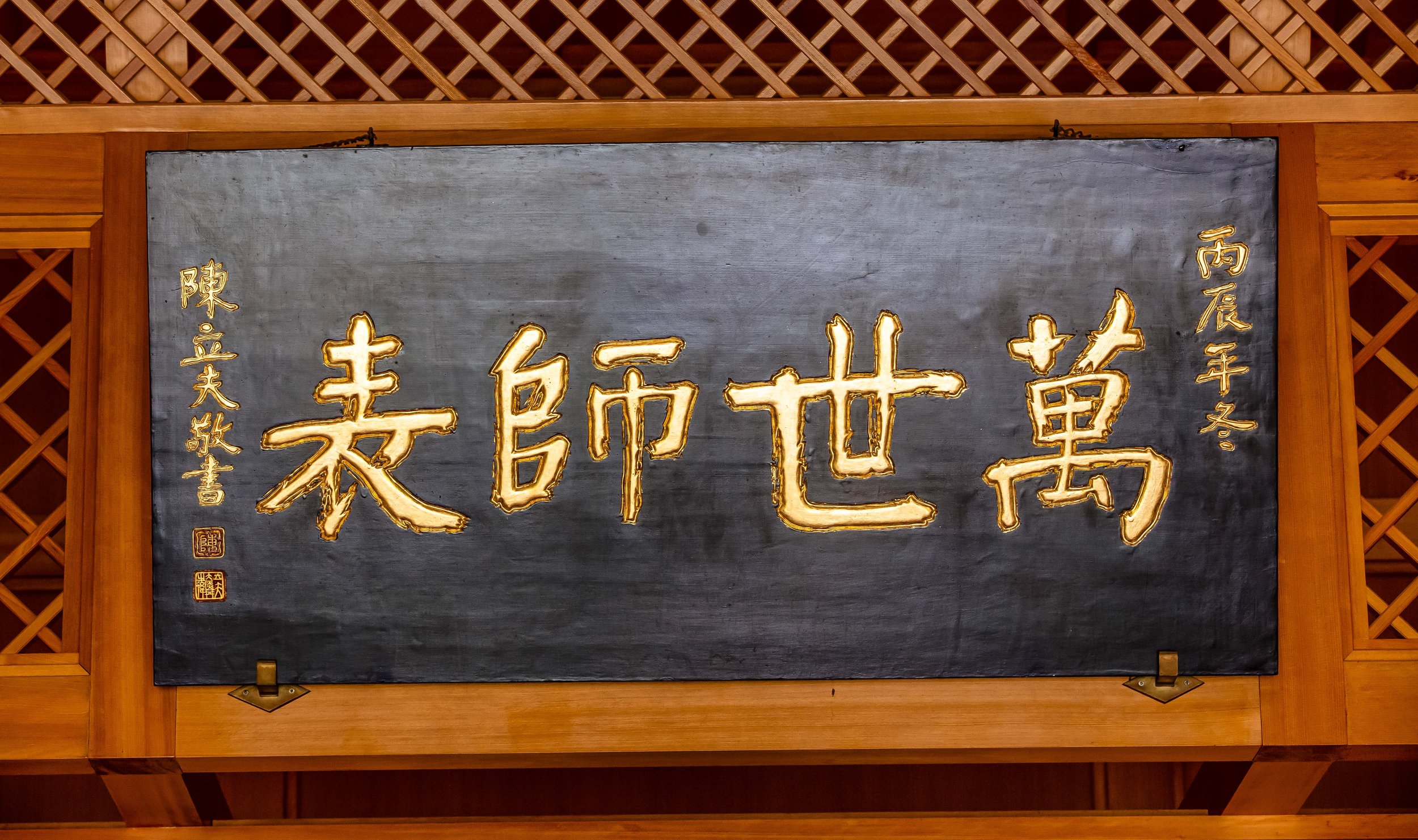

The first thing you’ll want to take note of are the three plaques placed just below the roof - The middle plaque reads “Naminoue Shrine” (波上宮) while the plaque to its left reads: “Peace reigns over the land” (萬民泰平) and the one on the right reads “National Protector” (國家鎮護). Given Naminoue’s position as the prefectural shrine as well as Okinawa’s unfortunate history, the plaques are quite fitting to the modern Japanese philosophy of non-aggression.

Hung from the lower beam of the gate you’ll notice something known as the “sacred rope” or the “shimenawa” (標縄). The rope is thick and expertly braided and is decorated with “shide” (紙垂), which are beautifully cut paper streamers that are used in Shinto rituals. These sacred ropes are found all over Japan and have many different uses but here at the Shinto shrine it is used to help ward away evil spirits.

In front of the doors you will find some hanging curtains with a circular logo on each - The crest, known as a “shinmon” (神紋) is the “mitsudomoe” (三ツ巴), which appears to be a comma-like swirl that is commonly associated with Hachimon Shrines (八幡神社) in Japan.

In Okinawa however the crest was adopted as the emblem of the royal family of the Ryukyuan during the First Sho-Dynasty around seven centuries ago. In Okinawa the crest is known as the “Hidari Gomon” (左御紋) and today you’ll find it not only at Shinto Shrines, but also at Shuri Castle and in most of the imagery that represents the islands. The crest is experiencing something of a resurgence in recent years as it was banned for several decades after the Japanese took control of the Ryukyus.

Link: 'Hidari Gomon' The Ryukyu Symbol (Budo no Kukyo)

The crest likewise has deeper connections with Okinawa’s Shinto Shrines as it is thought that the the origin of the design was inspired by the “Yatagarasu” (八咫鳥) or the ‘three-legged crow’, a common image throughout Asia, but is closely associated with Kumano worship. If you visit any of the Kumano Shrines in Japan, you’ll see images of the crow all over the place.

Link: The Legend of Yatagarasu, the three-legged crow and its possible origins (Heritage of Japan)

Most of what you’re going to want to see from the Hall of Worship is on the exterior, but if you’d really like to walk up to the doors to take a peak inside, you’re going to want to follow tradition and first follow a few steps which will impress the locals.

First you’ll want to walk up the steps to the wooden box in front of the main doors. You can drop in a small donation (there’s no set amount), then clap your hands twice to alert the kami of your presence, then with your hands clasped together, bow your head and make a wish. When you’re done, its tradition to bow. From there you can approach the open door and take a peak inside of the shrine room to see whats happening.

When you look into the interior of the Hall of Worship, you’re going to see a large open room with very little in terms of decoration and tables in the middle where the kami are located.

As I mentioned above, the Shinto Shrines in Okinawa adhere to Kumano Worship, one of the largest denominations (if you will) of the religion. Most of the information you’ll find online does a great job explaining the three UNESCO World Heritage shrines in the area and their history but does a poor job of actually explaining the deities enshrined within.

Officially, the shrine at Naminoue is dedicated to the ‘Kumano Deities’ but this becomes confusing as you can’t see the actual shrine. From my research, information suggests that the shrine consists of three mirrors which represent ‘Hayatama no kami’, ‘Kotosaka no kami’ and in the middle, the group of ‘Kumano deities’.

Where this gets confusing is that both of the gods are commonly associated and included within the group of ’Kumano Deities’ that I listed above. In this case, Hayatama no Kami, who is a water god and Kotosaka no kami, a protection deity, are likely given more importance given the importance of the ocean and farming to Okinawa. I’m clearly not an expert on this subject though, so if I’m wrong, please feel free to correct me.

Left -> Hayatama no kami -> 熊野速玉大神 (はやたまのをのみこと)

Centre -> Kumano Deities -> 熊野大神 (くまののおおかみ)

Right -> Kotosaka no kami -> 事解之男神 (ことさかのをのみこと)

Naminoue Beach

It is safe to say that If it weren’t for the beach below the shrine, this shrine would never have been built. A sacred space for the local Ryukyuan people for hundreds of years, the high cliff above the beach was the perfect vantage point for people watching ships making port in Naha from all over Asia.

Today the view of the ocean is blocked by an elevated highway over the beach, which kind of ruins the view, but the bridge does have its advantages as it allows people to take some pretty photos of the shrine sitting beautifully atop the high cliff.

Most notably for locals however is that Naminoue Beach is the only beach in the capital that is open to the public for recreational activities. The long white sand beach is a popular spot for locals to enjoy the scenery, have a BBQ or a picnic, play volleyball or go for a swim.

As mentioned above, the view at the beach is obscured by an elevated highway. While this does ruin the view for swimmers, it does provide an excellent opportunity for photos as there is a walking path along the highway where you’ll be able to get some shots of the shrine sitting atop the cliff above the beach.

If this interests you, you’re going to have to walk for about ten minutes to get to the bridge but getting there is fairly straight-forward. From the main gate to the shrine continue walking down Naminoue-dori where you’ll pass by a large driving school. Continue along the sidewalk until you reach the bridge where you’ll make a right turn onto the bridge.

Getting There

Naminoue Shrine: #25-11 Wakasa District 1, Naha (沖繩縣那霸市若狹町1丁目25-11)

MAPCODE: 33 185 023

Getting to Naminoue Shrine is quite easy and is even easier if you have access to the internet and Google Maps, given the difficulty of navigating Japanese-style addresses. I’d suggest though that you travel on foot as it will give you the best opportunity to explore as well as saving time and money.

If you’ve rented a car, you’ll definitely be able to find a car park nearby where you can drop off your car and check out the area. The problem with car parks though is that the parking fees are rather expensive and if you plan on checking out the shrine, the beach and the neighbouring Naha Confucius Temple, you’re going to need a bit of time. So, if you’ve got a car, the best thing to do would be to leave it where you’re staying, take the monorail and walk.

If you choose the latter, you can conveniently take the monorail to either the Prefectural Office Station (縣廳前站) or Miebashi Station (美栄站) and walk from there. I’d personally recommend walking from the Prefectural Office as it is a short walk and doesn’t require making too many turns, making it the easier route to navigate. The routes I’m sharing below might not be the fastest, but they require very little in terms of turning and getting lost in alleys. If you have internet access on your phone, just use your GPS and you’ll arrive in 20 minutes.

Directions from Prefectural Office Station

From the Monorail Station you’ll exit onto a large road named Onaribashi-dori (御成橋通り) where you’ll walk up the hill in the opposite direction from the Kokusai International Street (國際通). Simply follow that road until you reach the beach where you’ll make a left turn where you’ll quickly find the shrine.

Directions from Miebashi Station

From Exit #2 of the Monorail Station make a left turn onto Okiei Street (沖映通り) and then walk straight until you reach the end of the road along the ocean. From there turn left again and follow the coastal path until you reach Naminoue Beach and the Shrine.

If you’d like to take a bus, the shrine is serviced by Naha City Bus #2, #5, #15 and #45 where you’ll get off at the Nishinjo Stop. To catch any of these buses, simply go to the Prefectural Office Monorail station where you’ll find the bus stops on the road below the station.

Link: Bus Map Okinawa (Bus Routes / Schedules)

One of the most noticeable differences you’ll find in Okinawa from the rest of Japan is the absence and concentration of Shinto Shrines - Given the Ryukyu’s unfortunate modern history, it shouldn’t surprise you that there are so few left standing nor should it be surprising that the local people don’t always share a similar love of Japan’s state religion as those on the mainland. The situation with regard to cultural identity in Okinawa is a complicated one and as time passes, it tends to be one that drifts further and further apart from the rest of Japan.

Nevertheless, the lack of shrines does make the few left standing even more important. So, if you’re planning to visit Okinawa, you can expect that your visit to this shrine to be shared with quite a few locals.

Nevertheless, the rarity of Shinto Shrines in Okinawa makes the few left standing today important places of worship for those who adhere to the religion as well as for travelers.

As the highest ranking shrine in Okinawa Prefecture and the largest in the capital city of Naha, Naminoue Shrine has become an important place of worship for locals as well as a major tourist attraction, so if you’re visiting the city, you’ll definitely want to stop by to check it out.