One of my numerous personal projects over the past few years has been to research and document the weird and wonderful history of Confucius Temples here in Taiwan and the roles that they have played (or at least attempted), in shaping Taiwanese society over the past several centuries. Unfortunately, there are still a few that I haven’t had the chance to visit, so this little project of mine remains a work in progress.

I always enjoy having something to look forward to though.

When my girlfriend proposed a week-long trip to Okinawa earlier this year, my first thought wasn’t “Japan? Hells Yes!” Or “Beautiful beaches? Sure!”, it was “Did you know that Okinawa has a Confucius Temple that pre-dates most of Taiwans?”

To which I seem to remember receiving a bit of an eye-roll.

I might be a bit of a weirdo, but what better opportunity would there be to check out a Confucius Temple outside of Taiwan where I could compare relatively similar architecture and history?

So, as part of our itinerary, we added a visit to the Naha Confucius Temple, which is conveniently located nearby the city’s most important place of worship, the Naminoue Shinto Shrine (波上宮) and is somewhere she really wanted to visit anyway.

Before getting on our flight to Okinawa, I purposely didn’t do any research about the temple as I thought it better to walk in and look at it with a fresh set of eyes. I felt like I would be doing it a disservice if I walked in and compared it to the various Confucius Temples in Taiwan, which tend to be quite large.

What I did know however was that the Naha Confucius Temple rivals that of the Tainan temple in terms of its age and that it was an important place of worship for many of the Chinese settlers who migrated to Okinawa during the Ming and Qing Dynasties.

Going into this blind however almost ended up being a huge mistake.

I would later (luckily) find out that the Confucius Temple we had marked on our map was just the newest rebuild of the original temple and that there was also an older version located a short walk away.

So yeah, there are technically two Confucius Temples in Naha.

Initially, I figured that blogging about the Naha Confucius Temple would be a walk in the park like all of the other Confucius Temple’s I’ve become accustomed to writing about. In fact, whenever I visit one of these temples, thanks to their uniformity in design, I always know where to go, what to look for and how to make the most out of my visit.

These two were different though - not only because of their layout and their history, but I also had to learn a bunch of new terms in Japanese, which I then translated to Chinese and then again into English.

I was happy though to have been able to visit and learn about these historic places of worship and the important roles they played in Okinawan history and contrast that to the experience here in Taiwan.

The Naha Confucius Temple(s) might not be very high on the average tourists list of destinations when they visit Okinawa, but considering their historic and their cultural significance, it’s a shame that more people don’t know about them.

History

To learn about the history of the Confucius Temple in Okinawa, we first have to learn a bit about the history of the Ryukyuan Kingdom (琉球國), which ruled over the Ryukyu Islands between the 15th and 19th centuries.

The tiny island kingdom might seem rather insignificant in terms of the grand scheme of world history, but the role it played in the network of East Asian maritime trade cannot be understated. During its heyday, the Ryukyuan Kingdom was one of the busiest ports of call for all trade happening in East Asia.

Prior to the formation of the unified Ryukyu Kingdom, the islands were split up into three separate principalities known as the “Sanzan” (三山) or “Three Kingdoms” which consisted of “Nanzan” (南山), “Chuzan” (中山) and “Hokuzan” (北山).

In 1372, the Ming Emperor in China sent an envoy to Okinawa to establish tributary relations with the Ryukyuans. From then on, many Chinese were sent to the islands to engage in business or the affairs of state.

In 1416, Shō Hashi (尚巴志), then a prince of the Chuzan kingdom invaded Nakijin Castle (今帰仁城), capital of Hokuzan. He then formed a strategy to invade Nanzan and unify the three Ryukyuan Kingdoms under one banner - a plan which would take thirteen years to complete.

In 1429, Shō and his forces occupied Nanzan Castle (南山城), capital of the Nanzan Kingdom unifying Okinawa into one kingdom, with its capital at Shuri Castle (首里城) in Naha.

Emerging victorious and ending decades of strife between the three kingdoms, the Ming were quick to recognize Shō as the rightful ruler of the Ryukyu’s. This recognition gave legitimacy to his claims to the throne and the close relationship between the two kingdoms proved advantageous for both sides ensuring what would become known as the ‘Golden Age of Maritime Trade’ (黃金時代), making the kingdom one of the most important trading ports in East Asia.

Prior to the unification of the Three Kingdoms, China’s Emperor Hongwu (洪武帝) sent a group of 36 families from Fujian Province to Okinawa. The group, which would later become known as the ‘36 Clans of Kume’ (閩人三十六姓) settled in a small village in Naha known as ‘Kumemura’ (久米村), establishing the first overseas community in Naha.

The so-called ‘36 Clans’ were specifically chosen and sent for the purpose of aiding the kingdom in ship-building, promoting education, the sharing of technology and serving in the government in an official capacity.

It is unclear whether the number ‘36’ is factually correct, but what we do know is that the emperor sent Hokkien craftsmen, scholars and administrators to Okinawa to aide the kingdom in the development of a stable government and consolidating its naval power. The number of residents of Kume steadily rose over time and once the kingdom was unified, the influence of the village became much more significant.

Link: Ryukyu Bugei (琉球武芸) - “The 36 Clans of the Min-People”

Link: Kumemura (Wikipedia)

Kumemura was considered a privileged community comprised primarily of scholars, bureaucrats and diplomats and served as centre of culture and learning in the capital city for almost 500 years.

Today the area known as ‘Kume’ is geographically separated from the rest of Naha by the monorail and stretches from the Prefectural Office Monorail Station (県庁前駅) all the way to the port.

Today, the community prides itself on its literary and cultural significance and is widely regarded among locals as an area that has some of the best schools in the capital and for its Chinese cultural roots. After all these years though, Kume is also considered to be a bit ‘different’ than other areas of Okinawa.

With regard to the ‘difference’ created by the Kume community, it’s safe to say that the influence Kumemura had over the capital area created somewhat of a schism between the local inhabitants of the Naha area and other areas around the country.

This was due to the fact that the capital was culturally dominated by the Chinese immigrants for quite some time. Not only were the first schools in Okinawa ‘Confucian’ but the way the bureaucracy was run was also ‘Confucian’ in nature which mirrored that of the system set up in China. This led to the development of a Confucian set of values and policies that were almost non-existent once outside of the capital.

The dominance of Confucian values in the capital were not always looked upon favorably by the rest of Okinawan society which resisted, but the government’s push for modernization ultimately turned out to be successful in rooting out anything that was deemed to be primitive or uncivilized.

To assist in such efforts, Emperor Kangxi (康熙帝) gifted the capital its very own Confucius Temple in 1671 and from that time on royal rituals would be held at the temple in lieu of traditional Ryukyuan customs.

Indeed, one of the most unfortunate aspects of Okinawa’s modern history has been the concerted efforts by foreign powers (not only the Chinese, but the Japanese and Americans as well) to eliminate the culture, language and traditions of the Ryukyuan people.

These attempts, which started with the Confucian reforms in the 1600s lasted well into the 20th Century and only in the past few decades have the people of Okinawa been able to attempt to revive their language and culture.

Kumemura Confucius Temple (久米至聖廟) 1675 - 1945

As mentioned above, Qing Emperor Kangxi gifted a Confucius Temple to the people of Okinawa in 1675.

Confucianism though has played a role in Okinawa since the early 15th Century, which is significant (at least to me) because that predates its arrival here in Taiwan.

The original temple, which unfortunately burnt to the ground in 1945, would be 350 years old today.

For most of its 270 years of existence it served as a major centre for learning, was home to Okinawa’s first public school and was an important place of worship for commoners and royalty alike.

When Okinawa was annexed by Japan in 1879, the role of the Confucius Temple and the Kumemura community in general fell into decline. The on-site school would be converted into a public school under Japan’s national education system and any remnants of Confucian-style education or influence were removed.

A half century later, the bloodiest battle of the Second World War’s Pacific Theatre came to Okinawa.

What has become known as the Battle of Okinawa (沖繩戰) resulted in tremendous loss on both the American and Japanese side with an estimated 160,000 casualties. The people of Okinawa however suffered the most with the (estimated) pre-war population of 300,000 reduced by almost half with 149,000 killed.

The suffering of the Okinawan people at this time was exacerbated by the fact that they were (for the most part) just innocent bystanders caught in the crossfire. The aid-raids decimated much of the island and to make things worse, they were often arbitrarily executed in the streets by both the Americans and the Japanese leading to many families being completely destroyed.

In the aftermath of the war, almost ninety percent of the buildings on the islands were left destroyed and many cultural and historic treasures were lost. The people who were left had to pick up the pieces, rebuild their lives and also their homes.

When the war ended, as part of Japan’s terms of surrender, control of Okinawa was transferred to the United States and in conjunction with the newly formed Government of the Ryukyu Islands (琉球政府), the United States Civil Administration of the Ryukyu Islands (琉球列島米國民政府) were tasked with post-war reconstruction.

Most important to the Americans was that the islands infrastructure was constructed in a timely manner, to assist in their plans of constructing various bases on the islands, which to this day (in addition to their continued presence) remains a contentious issue with the locals.

The site of the original Confucius Temple fell victim to those development projects and instead of rebuilding the historic temple, a highway was constructed in its place.

Although there are few photographs available of the original temple, what we do know is that its construction and layout adhered to traditional designs of Confucius Temples with a Hall of Great Perfection (大成殿) in the middle of a large courtyard with buildings constructed on the east and west side. Later, an Education Hall (明倫堂) would be added and would serve as Okinawa’s first public school making the temple grounds a go-to location for your educational or literary needs.

Vocabulary Lesson

I’ve studied this stuff for a quite a while, but writing this blog forced me to learn a bunch of new vocabulary that required looking at stuff in Romanized Japanese, converting it to Chinese and then again to English. Let’s pause for a moment and take a look at some of the vocabulary to make it all a little easier to understand:

Guide: Romanji / Katakana / Kanji / Pinyin / English

Shiseibyō / しせいびょう / 至聖廟 / zhì shèng miào / Confucius Temple

Taiseiden / たいせいでん / 大成殿/ dà chéng diàn / Hall of Great Perfection

Meirindō / めいりんどう / 明倫堂 / míng lún táng / Education Hall

Tensonbyō / てんそんびょう / 天尊廟 / tiān zūn miào / Tianzun Temple

Tempi / てんぴ / 天妃 / tiān fēi / Princess of Heaven (Mazu)

Kume Confucius Temple (久米至聖廟) 1975 - 2013

Three decades after the destruction of the original Confucius Temple, a remake was constructed on a plot of land close to where the original was located. The two acre plot of land flanked by a small mountain near the Naminoue Shinto Shrine (波上宮) provided ample space for the construction of the temple.

The land used to construct the new Confucius Temple was originally home to a Taoist shrine named “Tensonbyō” (天尊廟), which suffered a similar fate to many of Naha’s buildings during the American air-raids. The temple was dedicated to Yuanshi Tianzun (元始天尊), an important Taoist deity, and provided a space for Taoists to worship in Kume.

The new version of the Confucius Temple, which in Okinawa is known as “Shiseibyō” kept with traditional Confucius Temple design layouts with access to the temple through a Temple Gate (至聖門) which opened up to a large courtyard with the “Taiseiden” (大成殿) in the centre. In addition to the Confucius Temple though, the grounds also included a rebuild of the Tensonbyō, an additional building named Tenpigū (天妃宮) and a Meirindō on the eastern side.

The situation at this Confucius Temple today is a bit different however.

When the Confucius Temple relocated in 2013, changes were made at this location to reflect the history of the grounds.

The Taiseiden, which was once home to the Confucius Spirit Tablet was converted back into the Tensonbyō and today serves as the main shrine of the temple complex. The main shrine is dedicated to Taoist deities who are known for their devotion to the country and the protection of those within it.

Inside you’ll find a shrine to Lord Guan (關羽), the Dragon King (龍王) and the Goddess Tempi who is better known as Mazu (媽祖). With the statues of the Dragon King and Tempi moved out of their individual shrines, the buildings on the western side of the grounds have been left empty and are currently closed to the public.

Likewise, the Meirindō currently serves as a meeting place for the Kume-Sōseikai (久米宗聖會), a local Confucian Association and also as a library of historical documents relating to the Kumemura area.

While this particular temple isn’t as large as what I’ve become used to here in Taiwan, nor is it as historic, its simplicity in design and the way that it blends into nature make it a spot you’ll definitely want to stop by for a visit, especially if you’re on your way to the Shinto Shrine nearby.

Confucius Temple of the Ryukyus (琉球孔子廟) 2013 - Present

On June 15th, 2013, the Confucius Temple returned home after a seventy year absence to the plot of land where the original 1675 shrine once stood.

The move, which was considered a “dream come true” for many “Kuninda-chu” (久米人) was one that signaled a restoration of an important cultural shrine that was lost during the war and spent seven decades in limbo.

The inauguration ceremony for the newly constructed temple was attended by the mayor of Naha and the governor of Okinawa while the Kume-Sōseikai Association took care of transporting the Confucius Spirit Tablets through the streets of Kume in traditional fashion.

Link: Mortuary Tablet of Confucius Returns to Kume after 69 years (Ryukyu Shimpo)

The newly constructed Shiseibyō sits on a considerably smaller plot of land in comparison to the previous location in Wakasa (若狹町) and Its layout also differs significantly.

The temple is a walled-complex with a large Temple Gate (至聖門) acting as the entrance which opens up to a courtyard with the Hall of Great Perfection (大成殿) directly in the middle. To the east of the Main Hall you’ll find the Meirindō that acts a community centre, place of learning and administration building (but is not generally open to the public).

The Taiseiden is where you’ll find the most significant differences between the temples - The shrine room is much larger with a high ceiling and more floor space on the interior. The main shrine, like every Confucius Temple has a Confucius ‘Spirit Tablet’ (神位) but is flanked by a statue of the Confucius (which breaks with tradition) gifted to the temple by Taiwan’s former President Chiang Kai-Shek (蔣介石) shortly before his death.

Keeping with tradition, on either side of the main shrine you will find shrines dedicated to the Four Sages of Confucianism (四配), Yan Hui (顏子), Zengzi (曾子), Zisi (子思) and Mencius (孟子), all of whom were Confucius scholars and authored books expanding upon the Confucian philosophy after the death of their master.

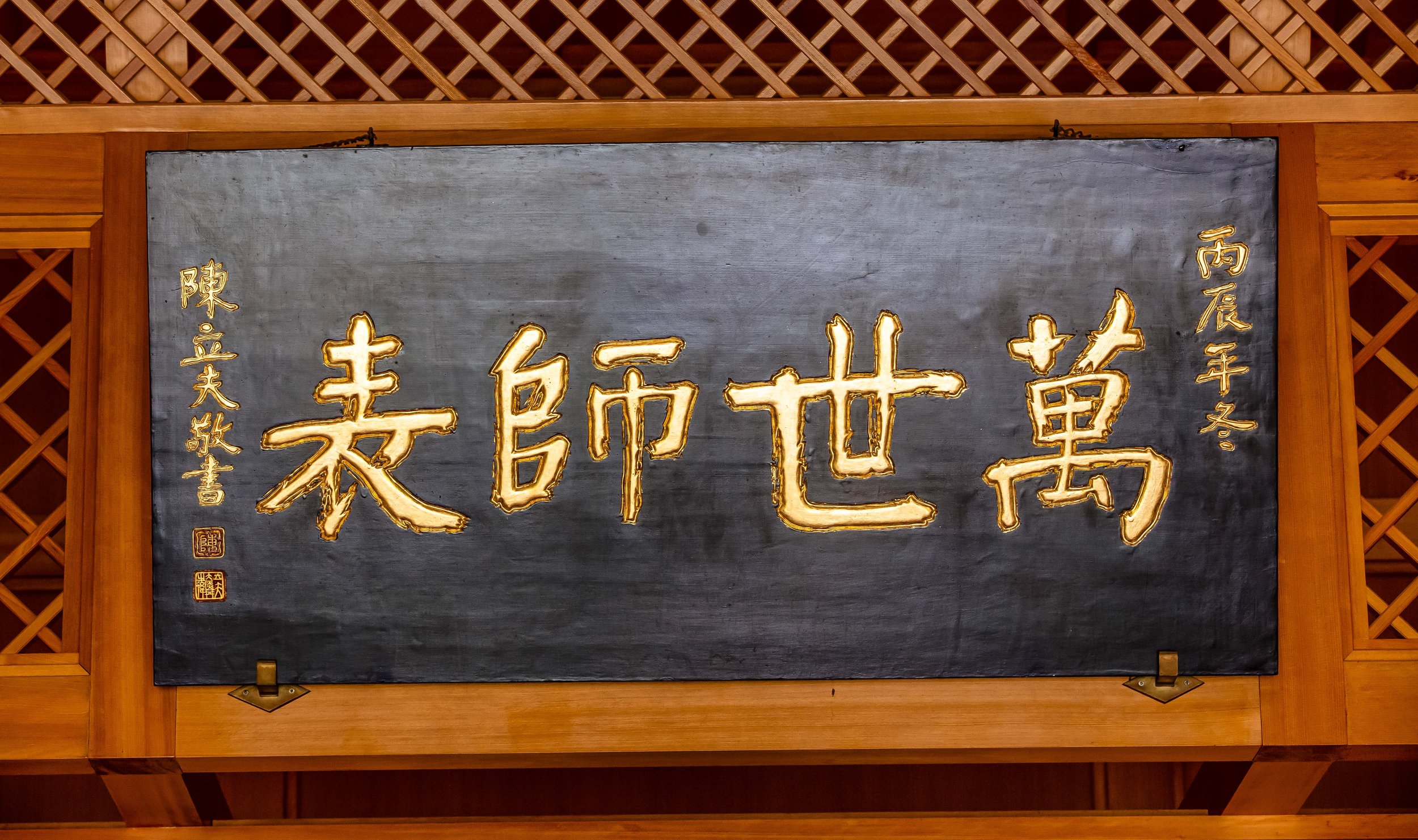

Like all Confucius Temples, you’ll also find plaques (御匾) placed above each of the shrines - The plaques always consist of four characters and are verses used to describe Confucius and his philosophy.

The phrases aren’t the easiest to translate, but I’ve done my best.

Above the main shrine you’ll find “The Teacher for all Ages” (萬世師表), on the left “Lessons that transcend time” (萬世師表) and on the right “Education for All” (有教無類).

The exterior of the Main Hall is elevated with a set of stairs on the left and right with a stone dragon mural between them. The design is relatively simplistic but you’ll want to pay attention to the two stone dragon pillars and the beautifully designed plaque above the main door that reads “Hall of Great Perfection” in Chinese characters.

Traditionally a Confucius Temple should also include what is known as the “Chongsheng Shrine” (崇聖祠) in a separate building to the rear of the Main Hall. The shrine is used to venerate the ancestors of Confucius as well as the various Confucian sages and philosophers throughout history.

At this temple, the designers took an approach that breaks with tradition, but to me seems quite ingenious considering the lack of space on the temple grounds. The Chongsheng Shrine at this temple is directly connected to the Taiseiden and is simply a small room to the rear of the building.

To reach the Chongsheng Hall, you just simply walk around to the back of the temple (right side) and you’ll find a door that opens up to a small shrine room. Unfortunately, like the main hall, you won’t be able to walk in to check it out.

Another interesting difference is that you’ll find another “Education for All” (有教無類) plaque placed above the shrine inside the Chongsheng shrine room.

You won’t typically find this kind of plaque in these shrine rooms (they’re always placed in the main shrine in honor of Confucius), but the temple found itself in a bit of a predicament when the Government of the Republic of China (Taiwan) gifted them with a new plaque.

So, to solve the problem, they simply put the older one in the back rather than throwing it into storage.

The Confucius Temple tends to be a quiet place and despite its cultural and historic importance, it doesn’t really attract many tourists. If you find yourself in Naha on September 28th however, which is known as “Teacher’s Day” (教師節) and Confucius’ birthday, you’ll be able to see the temple at its liveliest with ceremonies in honor of the sage.

Getting There

Getting to both of the temples is quite easy and is even easier if you have access to the internet and Google Maps. I’d suggest though that you travel on foot as it will give you the best opportunity to explore as well as save time and money.

If you’ve rented a car, you’ll definitely be able to find a car park nearby where you can drop off your car and check out the area. The problem with car parks though is that the parking fees are rather expensive and if you plan to visit the two temples as well as the Naminoue Shinto Shrine, you’re going to need a bit of time. If you’ve got a car, the best thing to do would be to leave it where you’re staying and take the monorail.

If you choose to walk, you can conveniently take the monorail to either the Prefectural Office Station (縣廳前站) or Miebashi Station (美栄站) and walk from there. I’d personally recommend walking from the Prefectural Office as it is a short walk and doesn’t require making too many turns, making it the easier route to navigate.

I’ve embedded a Google Map below which has the location of both temples and walking routes from both monorail stations.

For your reference, here are the addresses:

2013 Temple: #30-1 Kume District 2, Naha (沖繩縣那霸市久米2丁目30-1)

1975 Temple: #25-1 Wakasa District 1, Naha (沖繩縣那霸市若狹町1丁目25-1)

Naminoue Shrine: #25-11 Wakasa District 1, Naha (沖繩縣那霸市若狹町1丁目25-11)

If you’re visiting Okinawa and are expecting to see a bunch of historic temples, shrines and castles, you’re in for a bit of surprise. The Americans bombed the crap out of most of them during the Second World War and re-shaped the island into their own little military playground. Even though the original 350 year old Confucius Temple was burnt to the ground during the air-raids, the temple that was built in its aftermath as well as the current Confucius Temple are well worth your time if you are in the area.

Confucian history in Okinawa is an important case-study in the international relations of the Ryukyu people and speaks to the modern history of the Pacific islands. The temple also speaks to the long-arm of the Ming and Qing and how that history fuels China’s modern expansionist ambitions.

If you’re in the city and you plan on visiting the Naminoue Shinto Shrine, I recommend stopping by both the modern and the historic locations for the Naha Confucius temple. They won’t take you that long to visit, you’ll get some pretty pictures and you won’t have to deal with many tourists. Even if you’re not a Confucius Temple nerd like me, they’re certainly worth your attention.