Strangely enough, living in Taoyuan for the past decade, one of the most popular occasions of the year takes place at the end of the summer in the middle of Ghost Month when night markets pop up out of nowhere and the city comes alive with local culture and tradition.

The Mid-Summer Ghost Festival (中元慶典藝術節) seems to me a bit comparable to our 'Canada Day' festivities back at home when the whole community gets together to celebrate, enjoy a carnival-like atmosphere and eat some great food.

Like local people here in Taoyuan, I have found that after all these years of living here I have made it a tradition of my own to take part in the yearly festivities. The festival always end up being a great time and allows for me to get out with friends, take some photos, enjoy some local culture and good food and meet up with people that I might not have seen for quite a while.

Despite what I see as a great time, there is a dark shadow cast over the entire event thanks to the inclusion of the "Pigs of God Competition" which is viewed both as a cruel form of animal abuse and also as an important historic, cultural and religious activity that should be protected.

This is my third time to blog about this event and I’m sure that if you have read my previous posts you’ll likely notice a change in the tone for which I've presented it. The reasons for this are simply that my view has ultimately evolved with the times and as I've become more experienced as a blogger, my apprehension to discuss these aspects of culture and religion has started to fade.

I don’t like to criticize 'culture' and I don’t feel that it is my place as an outsider to actually criticize what the people of Taiwan do in their own country - but a tradition that in normal circumstances (without religion) would not be acceptable to most people has become a horrible spectacle of animal cruelty and has brought Taiwan quite a bit of unfair international condemnation and has also numbed onlookers to the needless animal suffering that takes place in order to celebrate a single night of 'culture' and 'folk-religion'.

My coverage of the 'Pigs of God' event as a photographer and also as a blogger over the past few years is not because I want to drive traffic to my blog or write about something sensational - I want to help people understand that this event is not indicative of Taiwan as a whole and if you educate yourself more about this beautiful island nation that you'd find that its an amazing place to live, study and work and that the people who live here are some of the kindest and friendliest people you'll ever have the chance to meet.

Pigs of God 2015 | Pigs of God 2016

Disclaimer

I just want to remind readers that as this blog moves on, there will be photos that you may not feel comfortable looking at. There is nothing particularly gruesome but I'm just warning you beforehand!

The event is often described by the international media as being ‘mired in controversy’ but locally it has the strange ability to arouse the curiosity of society at large who yearn for a bit of tradition in their hectic lives and is often perceived as a way to connect people to their heritage.

This means that while there are quite a few people who oppose it, there are others who make sure to visit and do their best to experience the ‘vibrance’ of Taiwanese culture while strangely taking family photos beside the carcass of dead animals stretched out and painted for the world to see.

The arguments for and against the festival go a little bit like this: Animal Rights Activists argue that this practice is not in line with modern Taiwanese society and that the tradition should cease to exist while supporters insist that it is a traditional aspect of Hakka culture and therefore it should be preserved.

Taiwan is a highly developed country where modernity and tradition are often at odds with each other, so when it comes to events like this groups who support these cultural traditions are often just as vocal as the opposition when their traditions are being targeted.

See: EAST - Environment & Animal Society of Taiwan (台灣動物社會研究會)

When I first came to Taiwan there were around five-ten giant pigs put on display per year. Friends tell me that when they were younger there were at least twenty or more. That number has slowly decreased with only three showing the year before last, two last year and two smaller ones this year as well.

I spoke to the director of the Taoyuan Yimin Temple (桃園市平鎮市褒忠祠) and he explained that there are fewer pigs this year due to "environmental concerns" (環保的關係) and the fact that fewer people are willing to raise the pigs nor do they have the space to keep them.

As the conversation about the ‘Pigs of God’ progresses and society learns more and more about the unnecessary suffering these animals endure during their short lives more and more people have started to oppose it - This opposition has put pressure on religious and cultural organizations to come up with new ideas and start making plans to eventually phase out the practice altogether.

Thus far over twelve temples have already stopped the contest and there are future plans for more to eventually put an end to it.

The problem however is that while some temples have 'promised' to put an end to the practice, it seems like they may be backtracking on these promises and ultimately may just keep practicing it until they’re forced to stop.

Before I focus on the negatives of this years event, I think its best to look at the positives and how things have improved over previous years:

- The Pigs of God this year were considerably smaller than years past which shows that a little more care was taken not to abuse the animals and overfeed them as much as in years past.

- The Taoyuan City Government promoted the usage of “Environmentally Friendly Pigs of God" (環保神豬) which were art displays made to look like pigs and constructed out of recycled products and paraded around town in the same way that the real pigs would be.

- The event organizers planned an alternate activity where local people as well as dignitaries as high up as President Tsai Ying-Wen would come and release water lanterns on the eve of the event.

As for the negatives, one of the things that bothers me most about all of this is how much local politicians have latched onto this event as a way to promote themselves. The event was attended by local and national level politicians from each party who mingled with the people.

The winning pig that was on display was either supported or promoted by a local DPP politician who had his flag next to the dead animal and office employees acting as a type of security in front of the pig.

When support for this event not only comes from local cultural and religious organizations but from politicians as well, it means that it is not likely that things are going to change very quickly and that is likely a sour spot for the animal rights activists who have worked tirelessly to help educate society about what is actually going on here.

At this point it seems like there has been a bit of progress and things have been changing for the better - I know that last year I seemed a little more optimistic that the practice would be ending after this year’s festivities, but right now, I can’t really see that happening.

There will be Pigs of God at the Mid-Summer celebrations next year as well.

If you are interested in watching some live video from the event in Hsinchu, check out this video from Far East Adventure Travel or this video from Taiwan Live.

The Pigs of God (神豬)

The practice of putting giant carcasses of dead pigs known as the "Pigs of God" (神豬) on display as a form of animal sacrifice is a tradition that started with the Hakka people a few hundred years ago here in Taiwan.

I should add however that animal sacrifice is something that has traditionally been common throughout almost all of the different Chinese ethnic groups.

While there are valid historic reasons why the Hakka people of Taiwan created such a tradition, the contest that has evolved out of it has become one of those traditional cultural practices that has struggled to stay relevant in modern times due to to societal changes and attitudes towards animal welfare.

To become a “Pig of God”, the animal is typically raised for anywhere between two to four years during which time they are force-fed in much the same way as a goose or duck in France is fed in order to make foie-gras. This allows for the pigs to grow to abnormal proportions with some reaching a final weight nearing almost a thousand kilograms before being slaughtered.

For a bit of clarity - market sized hogs sell when they are at about 250 - 270 pounds (113-122kg) meaning that a “Pig of God” grows to at least 5-6 times the normal size while winning pigs of the past have reached anywhere between 800-900 kilograms making them almost ten times the size of a normal healthy pig.

To achieve such a result the pigs are raised in a way that they are constantly overfed which eventually forces them to become immobile. This lifestyle is extremely unhealthy for the animals as they develop painful bed sores and often suffer from organ failure and various other ailments.

To add to the cruelty involved in raising an over-sized animal like this, Animal Rights groups claim that farmers often force-feed the animals heavy-metals or stones days before the contest takes place in order to achieve a higher final weight.

In the past the pigs would be taken out into the public square in front of the temples to be weighed and publicly slaughtered. This was a gruesome sight and one that I'm glad I've never had to experience.

Foreign media outlets however continue to falsely report that this is still a common practice as the pigs are brought out on forklifts, weighted and they slaughtered in front of cheering crowds.

Pigs of God History

The origin of the event is a bit difficult to explain, but it is one that coincides with the creation of the original Yimin Temple (義民廟) which was constructed as a place to memorialize Hakka militiamen and patriots who worked together to protect their homes and their families.

The spirit plaque (神位) that was placed in the temple to memorialize the fallen soldiers became known as "Yìmín Yé" (義民爺) and quickly became a community symbol that brought together Hakka people of all walks of life to celebrate their culture, identity and history.

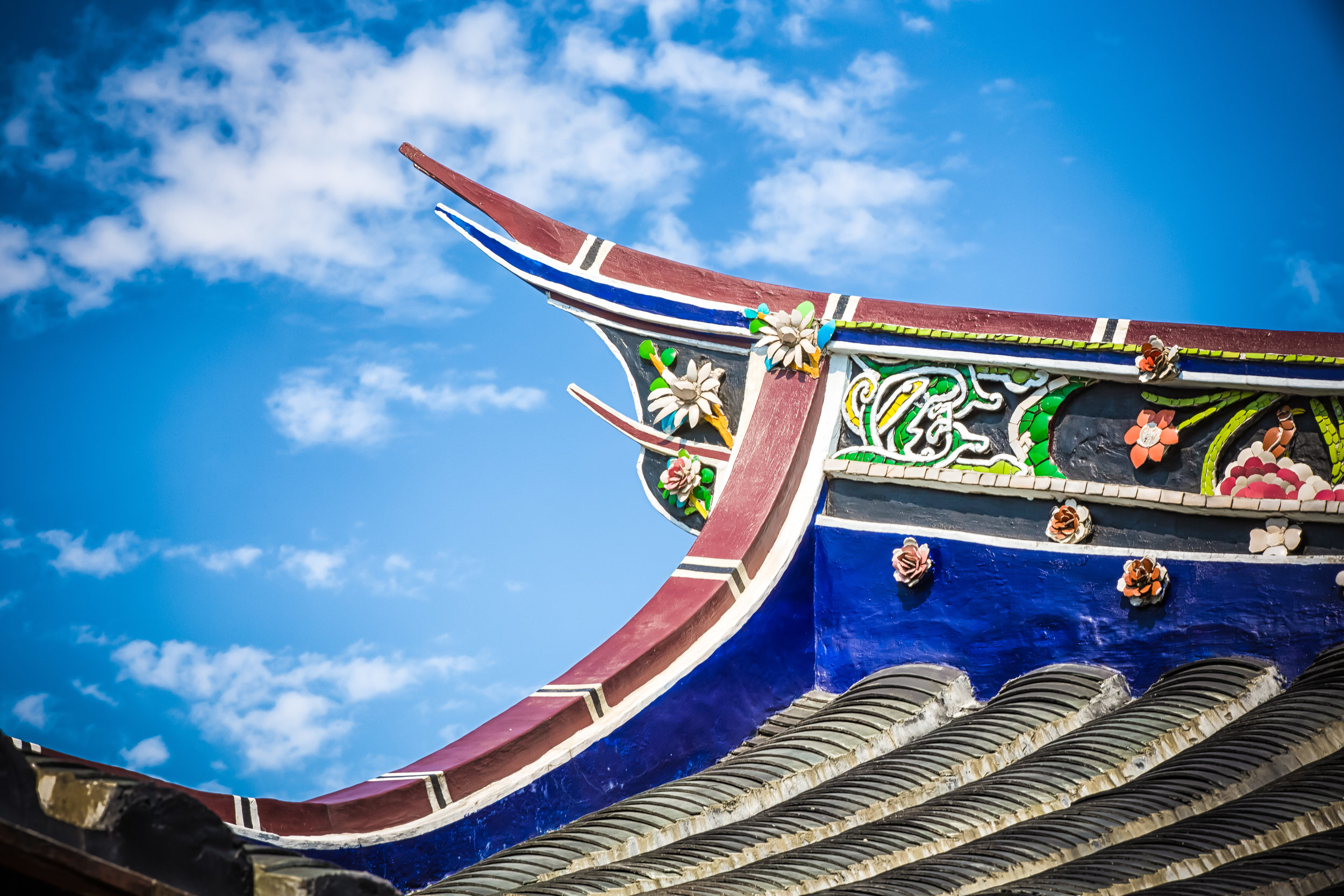

Every year in order to celebrate Hakka culture and the sacrifice of the young soldiers, the Yimin Cultural Festival (義民節) is held in conjunction with Ghost Month festivities (中元節) to honour Hakka ancestors as well as celebrate and promote Hakka culture throughout Taiwan.

The festival, like the Pigs of God has ultimately evolved into something quite different over the years, but the general purpose remains the same.

In the early days of the festival, the community in Hsinpu got together and put on a huge feast to honour Yìmín Yé.

As pork (in addition to chicken and duck) has been one of the most important animals to sacrifice to the gods and has always has been one of the most widely ingredients in Hakka dishes, it was always one of the most predominate features of the feast.

Each year one of the local families would have to raise a pig in order to both offer it up as a sacrifice to the Hakka ancestors and to help feed the community during the feast.

As “Yimin worship” became more predominant and ‘good luck’ was being attributed to paying respect in the temple, the annual feasts gradually became larger as a way to not only show gratitude but to also show off a families wealth and status in the community.

As mentioned above, the responsibility for raising the pig would ultimately rotate between the prominent Hakka families in order to ensure that each family did its part and that people wouldn't foolishly waste their money when they had such an important responsibility to the community.

This rotation went on for quite some time but soon a competition (of sorts) started between families as the pigs raised for the festival became larger and larger.

Ultimately the size of the pig that was offered up each year started to symbolize the wealth and power of a family meaning that as the years went by the pigs gradually became larger and larger as a show of “face” and local power.

When the problem of "face" comes into these kinds of things in Taiwan, a competition is bound to happen, and in this case, despite the tradition of rotating year-by-year it became expected that even in off-years people would still raise a pig to submit to the competition while at the same time offering gratitude to Yimin Ye.

Thus the Pigs of God competition became a thing.

With this history in mind we can likely agree that the 'Pigs of God Contest' was one that was born out of simple human vanity. This has nothing to do with culture or religion and that is why I believe that aspects of this tradition can continue while the contest should absolutely be put to an end.

As I mentioned in my introduction, the weekend of this festival is one of my favourite times of the year and is one that I’ve attended pretty much every year since I’ve come to Taiwan.

As the years have passed I stopped looking forward to the ‘sensational’ aspects of the festival and more so towards the coming-together of the local community to celebrate their culture and their heritage.

There are many ways to improve amazing festival while at the same time celebrating Hakka culture and history - I have seen with my own eyes that a lot of these changes are already taking place and that while the ‘Pigs of God' were an important aspect of the past, they are not an important part of the future.

I realize that this is a touchy topic and although its not my first time to blog about it, if you have any questions, comments, corrections or more importantly criticisms, don’t be shy - Comment below and I’ll get back to you as soon as I can!

Gallery / Flickr (High Res Photos)